Food waste is a growing global problem. Australians alone chuck out 7.6 million tonnes of food each year. That’s enough to fill 13,000 Olympic swimming pools. (Or the equivalent of more than 58 billion Iced VoVos. We checked).

The waste sent to landfill releases biogases, including methane. Methane’s a greenhouse gas that’s 28 to 100 times more powerful than carbon dioxide.

To put it into perspective, the United Nations estimates that 8–10% of global greenhouse gas emissions come from food waste. In Australia, it’s approximately 3%.

This is all really bad news for the climate – but it doesn’t have to be.

Cooking with gas

So what’s being done to tackle food waste here in WA? Murdoch University PhD student Chris Bühlmann has published research into how to harness it for renewable energy production.

He says there’s “tremendous opportunity” for a biological process called anaerobic digestion.

“[This] breaks down food wastes into biogas – a mixture of methane and carbon dioxide – to generate renewable energy,” says Chris. It sounds like a win-win but how does it work?

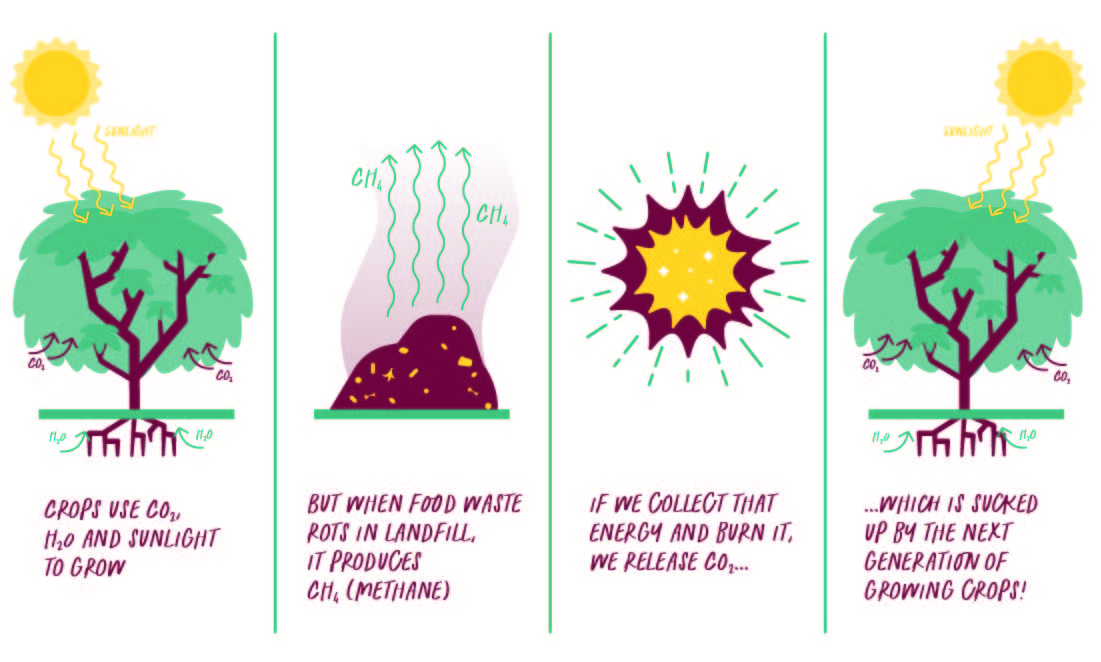

The idea is simple: capture the methane from decomposing food and burn it. Like burning other hydrocarbons, the chemical reaction releases heat (energy – woo!) and carbon dioxide (CO₂).

But CO₂ is bad, right? Yes, if we’re putting more into the atmosphere than we’re taking out. The good news is that CO₂ produced by burning methane is absorbed by the next generation of crops during photosynthesis. This means additional CO₂ isn’t being added to the atmosphere.

But wait, there’s more good news.

“There’s an additional CO₂ offset that accompanies anaerobic digestion as coal-fired power is substituted with renewable power,” says Chris. That CO₂ offset is more than you may think.

Recent research into the environmental sustainability of anaerobic digestion of household food waste found that 1 tonne of food waste in landfill produces 193kg CO₂-equivalents. On the flip side, producing renewable energy via anaerobic digestion offsets 39kg CO₂-equivalents per tonne of food waste.

That would save Australia almost 300 million kilograms of CO₂ every year.

Growing the industry

Anaerobic digestion does more than produce biogas. It creates lactic acid as a natural byproduct, which has been the focus of Chris’s research.

“The global market for lactic acid … has been growing rapidly and has been recently estimated to have a compound annual growth rate of 8% between 2021 and 2028,” says Chris.

Lactic acid is used in cleaning products, pharmaceuticals, food and cosmetics. Producing this chemical in a carbon neutral process can make biogas production more profitable.

Waging war on waste

In an ideal world, there wouldn’t be any food waste. Surplus food would be used to feed the hungry, like food rescue organisation OzHarvest is doing.

But this problem isn’t going to go away overnight, and Chris says anaerobic digestion is a way to put food waste to work.

“Most food waste is currently landfilled where it not only contributes to climate change, but also recovers little to no economic value from food wastes,” says Chris.

“However, biorefinery processes are able to recycle this food waste to produce valuable industrial biochemicals, modern biomaterials, and biofuels that can displace those produced from fossil resources.”

In the meantime, thanks to researchers like Chris, we can hope for a future where last night’s takeaway helps keep the lights on.