For far too long, women have been seen as secondary to men under the patriarchal rule of human society.

Yet, humanity’s existence has been a minor blip in the history of the Earth, where females are the dominant sex of many species.

The differences between men and women are far greater culturally than biologically.

In animals like the noolbenger/honey possum, females are highly promiscuous, forcing males to evolve some impressive anatomical changes.

A MAN OF SCIENCE?

Charles Darwin’s work in natural selection was pivotal to our understanding of evolution.

But there were a few holes in his theory of sexual selection.

Sexual selection is an idea Darwin made up, which he says is the process in which animals compete with each other in order to reproduce.

Credit: via Biography.com

In making this prediction, Darwin deemed females ‘passive’.

He cherry-picked data and skewed his results, deciding female animals were passive in the lives of their male counterparts.

Darwin insisted males were always in the business of wooing females, but females always submitted to males in sex and reproduction.

MAKE IT MAKE SENSE

Darwin determined that females couldn’t be promiscuous under any circumstances.

This is surprising, because he had evidence to the contrary.

In his 1871 book, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, Darwin is told a story about a female goose who mated with two male geese of different phenotypes (meaning they looked very different).

The goose then hatched babies that were clearly sisters from different misters.

Despite this knowledge, Darwin continued to assert that females gained no benefit from promiscuity.

He clearly hadn’t encountered the female redback spider. She eats the male after mating – taking ‘dinner date’ to a whole new level.

A ‘TRAVESTY’

Darwin wasn’t the only scientist who thought females couldn’t be promiscuous. Angus John Bateman had very similar ideas.

Bateman conducted a series of experiments on fruit flies that were very poorly designed.

He concluded female fruit flies received no benefit from being promiscuous, but males were better off if they mated with many females.

Credit: Shutterstock

Bateman applied this idea to every animal in the animal kingdom, including humans.

Patricia Gowaty, a professor in evolutionary biology, dug up Bateman’s lab notes and recreated his experiment. She found Bateman’s experiment was full of flaws.

Most notably, Bateman counted fathers as parents more often than he counted mothers as parents, which is impossible given you need both to reproduce.

In fact, Gowaty called Bateman’s experiment a ‘travesty’.

FLAWED RESULTS

Bateman also failed to realise a quarter of the fruit flies would die from the mutations inherited from its parents, influencing his results.

In Gowaty’s version of his experiment, female fruit flies benefited from being promiscuous and mating with multiple males, although to a lesser degree than males.

Bateman chose results that matched his expectations and fit nicely with Darwin’s idea of passive females and promiscuous males.

This was a nasty case of confirmation bias.

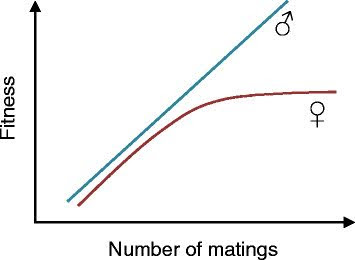

A SLIPPERY SLOPE

The idea that males benefit from multiple matings and females don’t is known as ‘Bateman’s Gradient’.

Credit: Edward Morrow, 2015

Bateman believed promiscuity would only benefit males because of a phenomenon called anisogamy.

Anisogamy is the distinct difference in gamete size many animals – including humans – have.

Gametes are sex cells, like sperm and eggs in humans. Human sperm are very small compared to eggs.

This was the sole premise Bateman relied on to conclude that because males can be foolish with their DNA, they benefit from promiscuity but females don’t.

STAY CALM AND THINK OF ENGLAND?

British ornithologist and Emeritus Professor of Behavioural Ecology Tim Birkhead outlines this sentiment in his book, Promiscuity: An evolutionary history of sperm evolution.

“If the number of males and females are approximately equal, how can most males copulate with many females and most females copulate with only one male?” says Tim.

“The presumed answer was that … females did copulate with more than one male but reluctantly.”

“On being approached by another [male], they lay back and thought of England, but their hearts weren’t in it.”

However, Birkhead and I both know this was not the case. Those ladies were thinking of anything but England.

ALL SWEET FOR THE HONEY POSSUM

Although Bateman is long dead, his gradient is still in textbooks and the idea that females are passive, choosy and not promiscuous is still taught in biology classrooms.

However, there are plenty of promiscuous female animals.

The honey possum (Tarsipes rostratus) is highly sexually promiscuous. They are classified as polyandrous, which means one female mates with multiple males.

Endemic to WA’s southwest and known by Noongar people as noolbenger, these animals are about the size of your thumb.

Each honey possum litter has two to four young, although no more than three will survive.

Credit: Simon Colenutt via iNaturalist (CC BY 4.0)

Although these young are born at the same time, they may only be half siblings. When honey possums mate with multiple males, their litters could have multiple fathers.

While most litters are sired by two males, it’s possible for three young born at the same time to have three different fathers.

The female honey possum doesn’t know which male is the father to her babies, like a Discovery Channel’s Bridget Jones’ Baby.

MELON BALLS

In species where the female is more sexually promiscuous, males have to engage in sperm competition in the hopes their genetic material is passed onto the next generation.

The bigger the sperm and more of it, the better chance a male has of being a father.

To help their cause, males of species with promiscuous females have evolved large testicles.

Male noolbenger’s testicles make up 4% of their body weight. That’s like an average-sized human male having testicles the size of rockmelons.

Credit: © Henry Cook, via Flickr

Male honey possums also have the largest sperm of any mammal.

This is despite having the smallest young, the size of a grain of rice.

Research suggests females who are promiscuous have a greater likelihood of reproductive success, because they gain genetic material from different males.

They can then pass the diverse genes onto their offspring and potentially gain greater access to resources.

Honey possums aren’t alone in their promiscuity. Antechinus’, echidnas, dolphins, bees, crickets, frogs and 90 percent of bird species are all highly promiscuous.

Imagine a world in which all human females were mating with multiple males, men might start evolving rockmelon-sized testicles.