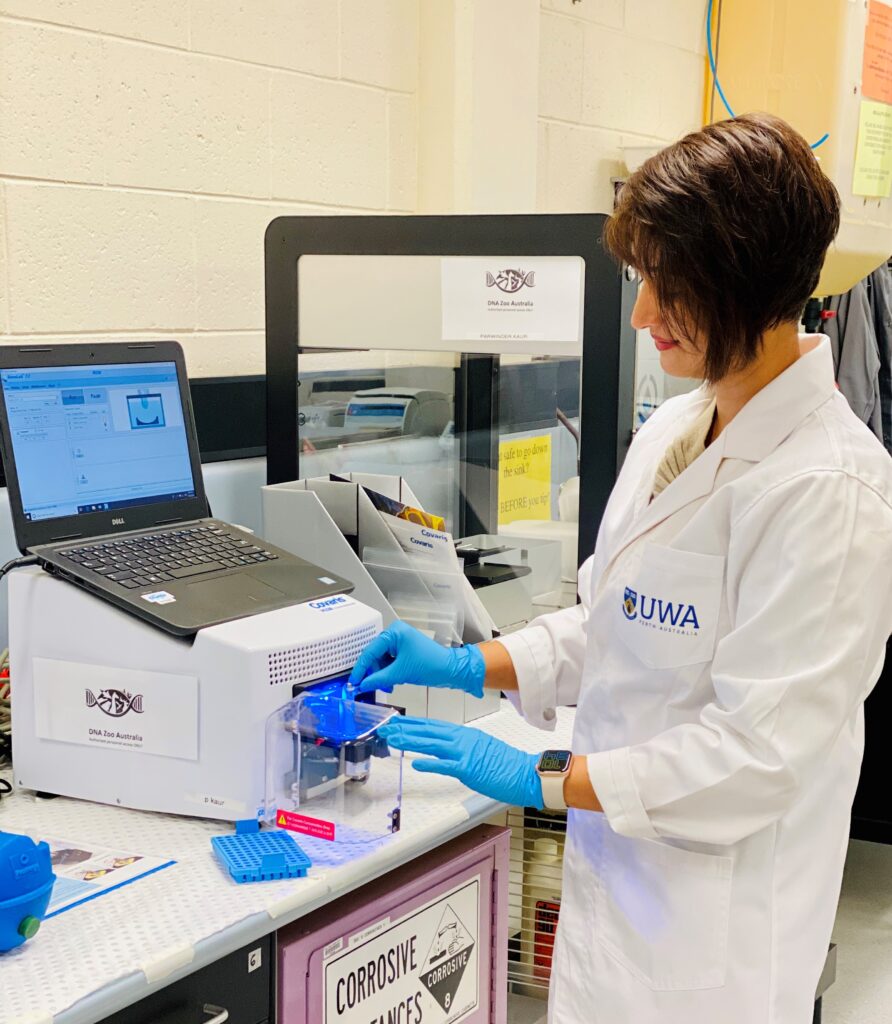

Earlier this month, researchers from UWA produced a complete genome for arguably WA’s most famous marsupial. Then they uploaded it to the internet, for anyone to access, as part of an international project called the DNA Zoo.

Here’s why that’s a big deal – and it’s not for the reasons you might think.

But first – how?

Extracting DNA is easy. You can do it with a blender in your kitchen. The hard part is reading it. DNA lives in tightly packed structures called chromosomes, so to read it, you kind of need to break it first.

Rather than smashing the whole structure, like earlier techniques, the DNA Zoo approach tries to keep related parts of the chromosome together.

“Basically, we photograph the DNA in three dimensions, and we do it using 1% formaldehyde,” says Parwinder Kaur, Associate Professor at the Faculty of Science at UWA and Director of DNA Zoo Australia.

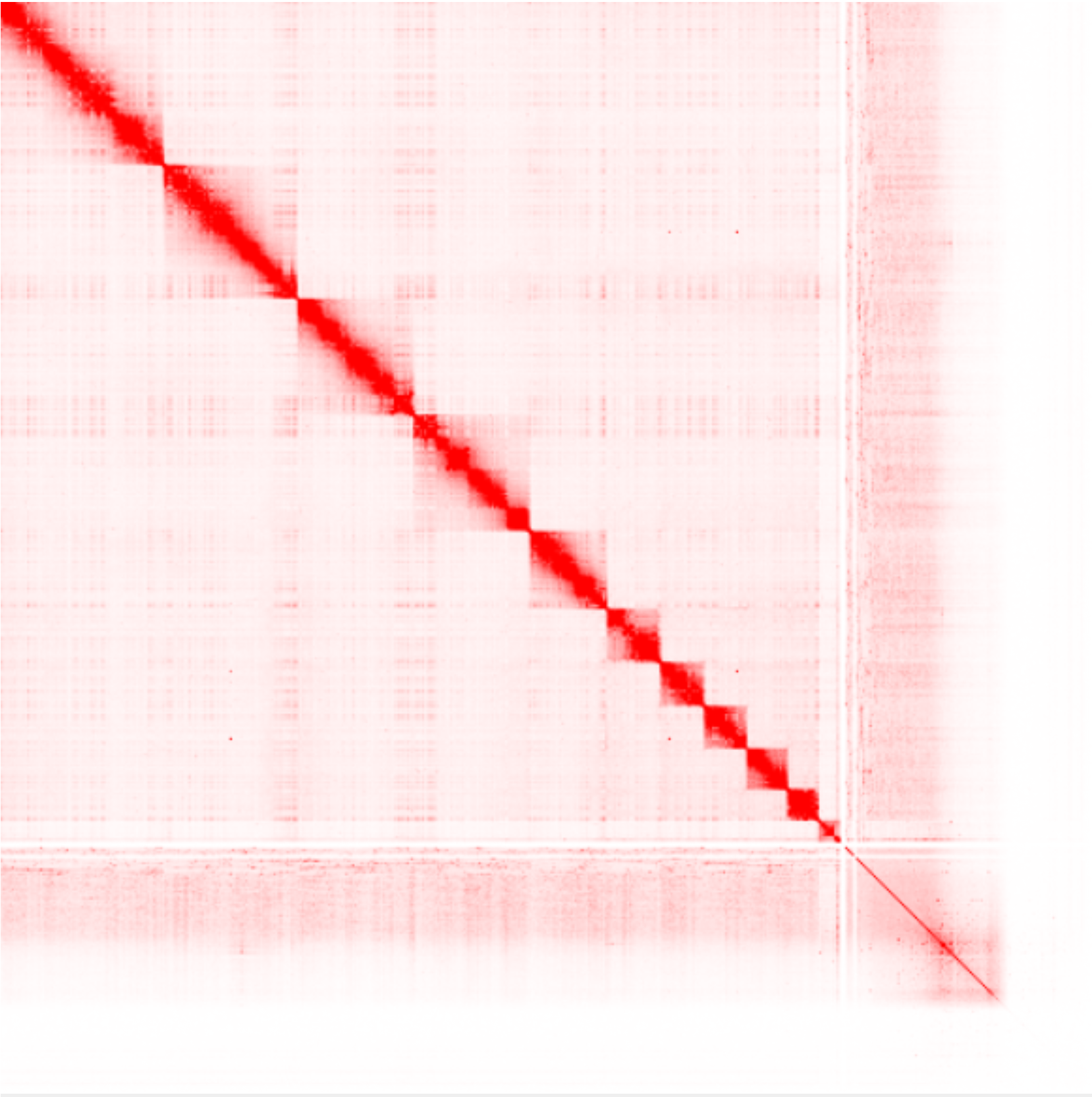

Then, when the time comes to put it back together into a sequence, that extra information helps reassemble the sequenced pieces in a computer.

“We learned this from Facebook in a way. Sometimes when you post a lot of photos on Facebook, Facebook comes back and starts suggesting relationships. You post a lot of photos with this person, you guys must be related. So it’s the same approach for DNA,” says Parwinder.

"It’s just a very clever way of looking at the DNA, unpacking it and then putting it all together.

That makes it faster, easier and way, way cheaper – a species’ complete genome can be sequenced for $1000.

“If it was $2 million or even $1 million, I’d have to write I don’t know how many grants to get the quokka genome. All I need now is just to go ask for samples,” Parwinder says.

(Those samples, by the way, come from vets and other researchers who already work with the animal population. No quokkas were harmed in the making of this genome.)

Once all that’s done, the DNA Zoo team releases the whole lot online, free for anyone to use. But what exactly are people going to use it for?

Welcome to Quokka Park

Let’s start with the obvious question: does this mean we can clone the quokka? Should the unthinkable happen and quokkas go the way of the dinosaurs, does this mean we can restore the species from their freshly uploaded cloud backup?

“With the technological advancements, probably in the next 5 to 10 years you will be able to do it, yes,” says Parwinder.

“But I ask you a question back for this one. Would you spend all your resources cloning something back which you’ve already lost? Or would you spend your resources to save what you are going to lose?

“You can probably bring back the Tasmanian tiger. But can you let your devil go? Can you let your quokka go? Can you let your koala go?”

The point of projects like DNA Zoo isn’t to bring species back – it’s to stop them going extinct in the first place.

Macropod Matchmaking

To understand how, we need to look at what DNA data is actually useful for.

There are two quokka populations – one on Rottnest and one on the mainland. Quokkas may be abundant on Rotto (and on Insta), but that doesn’t mean they’re not threatened.

“There were about 500 quokkas which were living on the mainland, and in 2015, the wildfires wiped them out. So from 500, we got down to 39,” Parwinder says.

Small populations in a small area are much more at risk of extinction.

“Just one wildfire and you lose them all,” says Parwinder.

Unfortunately, it also makes the solution harder. Fewer quokkas means fewer copies of the DNA out in the wild. That means there’s a much larger chance of weak or damaged genes being passed on to future generations. Breeding programs can work around that – but it helps if you know what you’re looking for.

“Because we’ve got a reference genome, we will be able to exactly map what level of genetic diversity is left on the mainland and then which are the best bets in terms of breeding,” says Parwinder.

Marsupial superpowers

The genome also helps us better understand what unique adaptations a species might have. That’s not so we can build a human-quokka hybrid, but so we can understand how they might deal with an increasingly uncertain future.

“There is no DNA code available for a lot of species which are already gone from the planet,” says Parwinder. “There’s things that we’re not gonna know about them and all the superpowers they had, all those little adaptations.”

Genes can determine how well a species deals with disease, new habitats, new food sources and even climate change. Knowing what genes the quokka has lets us know where they might need help and how we might help similar species too.

Genetic data can also help us understand diseases spreading the other way, from animals to humans. That transfer is called zoonosis, and it’s an understandably hot topic right now. It’s also why you really shouldn’t pat the quokkas, even though they’re really cute.

If you love something, do it for free

So a genome isn’t a backup of a species for future scientists to restore. It isn’t about building superheroes. It’s about helping quokkas make the most of the superpowers they already have so that mammoth effort of de-extinction isn’t needed.

That’s information, Parwinder says, that researchers and conservation bodies could be using straight away.

“It may take me two years to put a good publication together, which will appear in a nice decent journal.”

“Who knows what could happen in those two years.”

“So it’s all publicly accessible, and anybody who’s good at coding, who’s good at wildlife knowledge, can join in. And we would love to have more and more people join to share it and help us.”