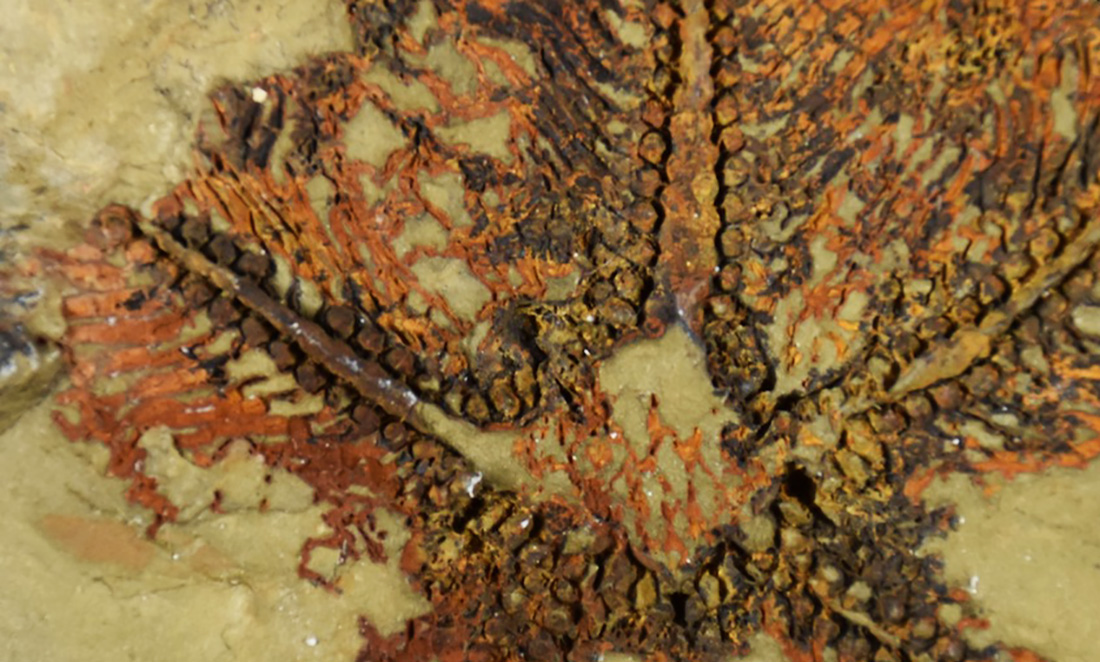

Scientists have discovered the world’s oldest starfish-like fossil.

The ancient animal – known as Cantabrigiaster fezouataensis – is the ancestor of all living starfish and brittle stars on the planet.

UWA adjunct research fellow and Cambridge University visiting postdoctoral researcher Dr Aaron Hunter led the research.

He says the specimen was first collected in the early 2000s by Berber farmers turned fossil hunters in the Moroccan desert.

“It’s a fossil that’s perplexed me for many years,” Aaron says.

Starfish ancestor

The turning point came while Aaron was studying living specimens of sea lilies or crinoids – a close relative of starfish.

The specimens were collected off WA’s northern coast and stored at the WA Museum.

“I looked at their arms and I thought, well, that looks familiar to this fossil that I have in my collection,” he says.

“It was about the time I realised this fossil … could actually be the ancestor of all starfish-like animals.”

To test the theory, Aaron and his team examined starfish fossils from 480 million years ago to 350 million years ago.

“The result was that, yes, it really is this missing link,” he says.

An alien ocean

If you had a time machine and went back to the period C. fezouataensis is from, there would be no life on land, Aaron says.

“On the land, it would be a dead continent,” he says. “No plants, nothing there.”

If you donned a snorkel and put your head underwater, the ocean would be filled with bizarre animals.

“You wouldn’t recognise anything … it’d be like something out of an alien film. But in the middle of that, you would recognise your starfish,” Aaron says.

“They may well be one of the first modern animals ever to appear on our planet.”

Starfish on a stick

Aaron says C. fezouataensis likely descended from crinoids, which resemble a starfish on a stick.

“Crinoids are like a starfish. They have arms, they have these little tube feet … but they have a stem,” he says.

C. fezouataensis is the first animal to lose the stem, put its mouth on the surface and adopt a starfish body plan, Aaron says.

“It’s quite an amazing discovery,” he says.

Aaron named Cantabrigiaster after the two cities of Cambridge – one in the UK and one in the US.

“We’ve acknowledged that all of these amazing scientists who worked in both cities over the last 100 years or so or more were involved in trying to resolve this problem,” he says.

“We didn’t know where starfish came from.”

Fossils for sale

Aaron says the first C. fezouataensis fossil landed on his desk through a friend who had picked it up on a field expedition. Later, a series of specimens were put up for sale through an online auction website.

A Yale University professor recognised the importance of the fossils, bought them himself and donated them to Yale.

It allowed Aaron to access the fossils for his research.

“We rescued a huge chunk of the specimens,” he says.

Despite studying fossils all over the world, Aaron believes some of the most beautiful brittle stars ever preserved are from WA’s Gascoyne Junction.

“I’d call that iconic level,” he says. “It really is beautiful because they’re so big.”