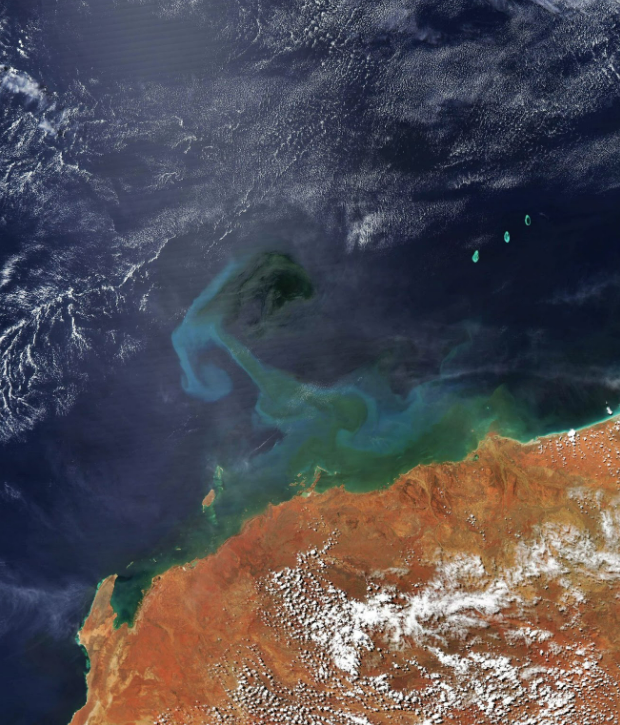

Have you ever happened across a body of water completely covered in a mysterious green slime?

What first seems like some type of unsettling waterborne disease is simply an algal bloom.

Algal blooms occur when microalgal or macroalgal species proliferate to huge numbers in aquatic environments.

Blooms can colour both fresh and salty waterways green, red, brown or gold. Sometimes only testing can confirm the presence of an invisible bloom.

The most common type of freshwater microalgae is cyanobacteria (blue-green algae).

In oceans, you’ll most likely run into dinoflagellates (fire/red-tide algae) or diatoms (yellow-green algae), although both these species occur in freshwater too.

Despite appearances, they are often completely harmless, and larger algae species are even common food sources for people around the world.

Caption: Cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae, can appear in all types of aquatic environments

Credit: CSIRO, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Not quite a plant, not quite a fish

Algae is the blanket term for organisms that live in waterways and survive by converting sunlight into energy, as terrestrial plants do. Sometimes they’re microscopic unicellular creatures, other times giant kelp as tall as Norfolk pines.

Unlike terrestrial plants, algae lack roots, flowers and stems.

This is what led to their categorisation as Protista. They are not plants, animals, fungi or bacteria.

Glowing bioluminescent algae varieties wow tourists the world over. They’re the origin of the fossil fuels burnt to power society for centuries, and they convert atmospheric carbon dioxide into so much oxygen that we can thank them for roughly half of the breaths we take.

At their worst, harmful algal blooms decimate ecosystems. In rare cases, they poison those hoping for a succulent seafood meal.

In WA, the Swan River is cursed with regular cyanobacterial blooms, forcing fish to relocate to clearer waters.

Over in South Australia, an ongoing dinoflagellate bloom has swollen to the size of Kangaroo Island, killing over 200 different species of marine life in the process.

Caption: A dark-blue, dinoflagellate bloom in the state of São Paulo, Brazil

Credit: NASA Earth Observatory Images by Joshua Stevens, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Bloomin’ algae

Gustaaf Hallegraeff is Emeritus Professor at the University of Tasmania and has researched harmful algal blooms for many years.

He says algal blooms are generally classified into three categories. The first is typified by general discoloration of the water.

“It’s unpleasant, the public complains,” says Gustaaf.

“It’s not nice for swimming, so it can have an impact on tourism. Sometimes beaches can be closed, but there’s no harmful chemicals involved for humans.

“The second category of algal blooms can kill fish,” he says. “But they’re still not harmful to human health.”

Massive fish and marine life casualties are a common occurrence after excessive algal growth. Gustaaf says this isn’t necessarily a result of algae toxicity though.

“These blooms can become so dense that, if they die off, they lead to low oxygen conditions,” he says.

“Sometimes you see dead fish on the beach, and people immediately think the worst – there’s a toxin involved. But it is low oxygen conditions.”

A thousand algal blooms

“The second scenario is really impacting fish in farms,” says Gustaaf. “I was involved in one scenario in the salmon industry, and in a week, it killed US$800 million of fish.”

The third category is the biggest cause of concern.

“This involves powerful species that produce chemicals which can cause human health problems, and many of them can accumulate in shellfish,” says Gustaaf.

Caption: Toxic algae rarely appears in fish but can easily accumulate in filter feeders like shellfish

Credit: Jpatokal, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

“Sometimes they can accumulate in lobsters or scallops, mussels, oysters, but very rarely do they accumulate in fish. There’s only one such scenario.

“It’s not necessarily the case that fish flesh would be contaminated.”

Where’d you run-off to?

Algal blooms have many causes, but it’s commonly chemicals in industrial fertilisers that end up in rivers and oceans in a process called run-off that leads to intense blooms as the algae feasts on phosphorus and nitrogen.

In Australia, blooms are often predictably worse in spring and summer, especially during periods of heavy rainfall.

“You get a regeneration of nutrients over winter, and it comes back to the surface with the new sunlight in spring,” says Gustaaf. “These diatom blooms are really good for the food chain – they lead to edible fish.”

Warmer water means it’s bloom time

There’s considerable evidence indicating climate change is impacting the global increase in harmful algal bloom events.

“The whole system of understanding algal blooms at the moment is becoming less and less predictable,” says Gustaaf .

As ocean temperatures continue to warm, some types of algal blooms will be able to navigate the new ecosystems while others won’t.

It’s difficult to predict what this dynamic and complex situation will look like in the waters of tomorrow.