We’re in the midst of a global waste crisis.

From the ‘Great’ Pacific Garbage Patch to the microplastics seasoning your cereal, the rubbish we ‘throw away’ seems to crop back up almost everywhere you look.

Food Organics and Garden Organics, also known as FOGO, is a government initiative aimed at tackling the waste crisis.

FOGO is based on the idea that sorting our waste is easiest at the top of the chain: our kitchens.

Is this subtle change to a weekly chore really the solution to a pressing global issue?

WASTE NOT, WANT NOT

Humans have been thinking about where to dump their rubbish since time began.

Landfills date back to 3000 BC. Mounds of human byproducts – called middens – may be as ancient as 130,000 years ago.

Everything changed in the 20th century. Enter plastic. This highly useful material doesn’t decompose. It just breaks down into tinier and tinier pieces until it becomes inorganic microplastic dust, like hyper-coloured sand.

Caption: Microplastics have been found from the top of Everest to the bottom of the Mariana Trench

Credit: OceanBlueProject, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Australian households were responsible for 12.4 million tonnes of waste in 2019, of which around 10% was plastic.

Each of us generates over 300 kilos in wasted food a year

Even after we die, high-level nuclear waste is stored deep underground in facilities designed to deter interaction for the 100,000 years it will remain radioactive.

THE CRUST OF THE ISSUE

Lauren Goodheart is a Resource Recovery Specialist at Australia’s leading waste management company Cleanaway.

She says population growth has significantly influenced the issue.

“As the population grows and urbanisation increases, consumption patterns shift,” says Lauren.

“People are buying more packaged goods, eating more processed foods and creating more waste – driven by busy schedules, convenience-oriented food choices and a throwaway culture.”

The responsibility doesn’t lie solely with the consumer though. Governments and corporations have plenty to answer for.

“Brands are always promoting new food products to consumers and output these products at high volumes, which doesn’t always equate to the consumer demand,” says Lauren.

“They then expire and go to landfill.”

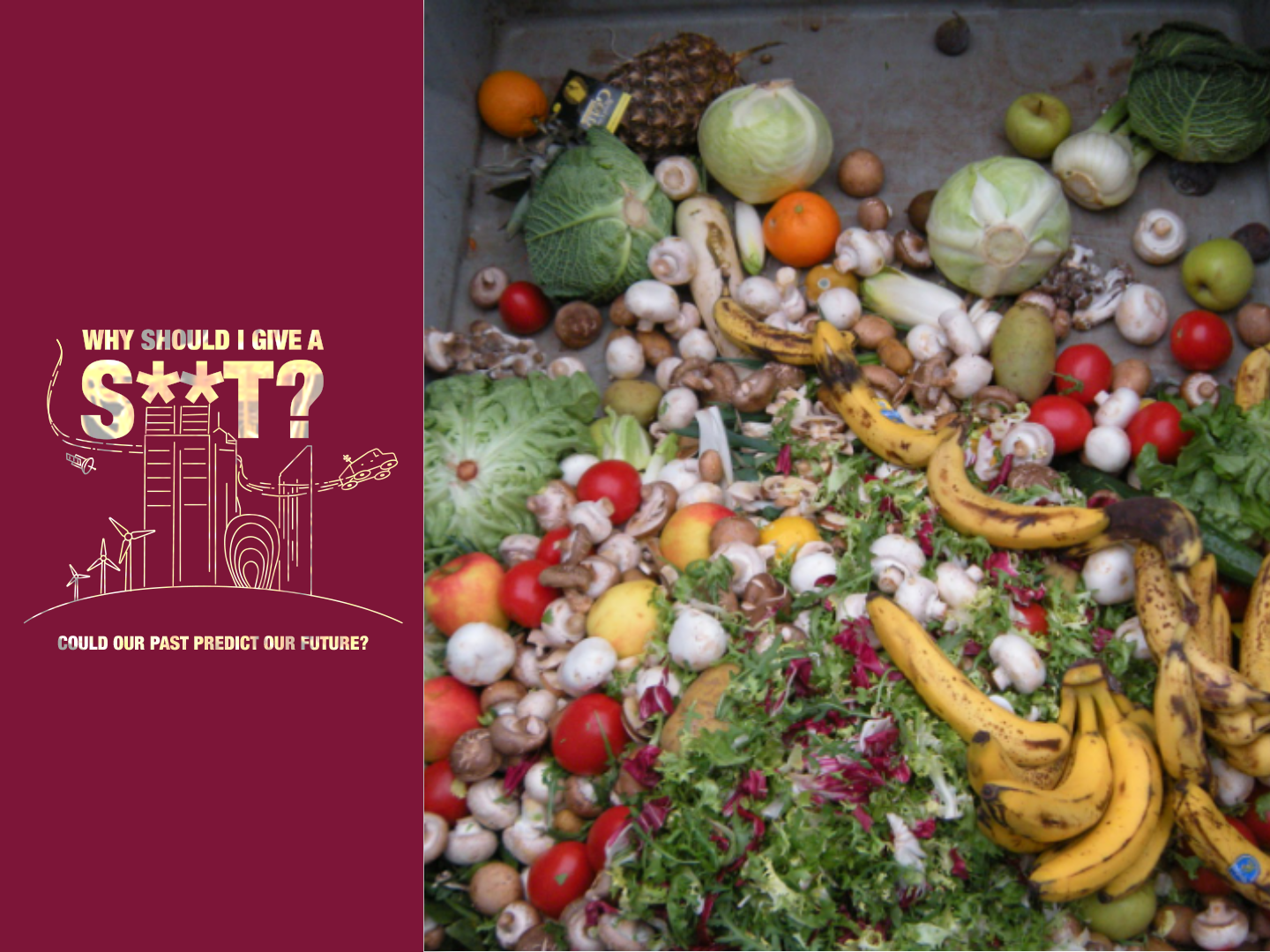

Caption: Australia produces 7.6 million tonnes of food waste a year

Credit: petrr, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

IS FOGO A NOGO?

As the walls of rubbish continue to build around us, scientists have a few hopeful solutions.

In China, one of the world’s leading waste producers, researchers are emphasising an approach called co-production.

Co-production means the issue must be tackled culturally at all levels – from the consumers at the bottom, through the supply chain, to the institutions at the top. Everyone is involved and responsible.

“Waste recycling systems should help change behaviours, not enable bad habits,” says Lauren.

“If we rely solely on recycling while continuing to overconsume and dispose of materials carelessly, we’re missing the bigger picture – waste avoidance.”

She says waste education and awareness are critical, as well as campaigns like The Great Unwaste and OzHarvest.

The Great Unwaste initiative aims to shift the mindset from waste disposal to resource recovery, encouraging people to rethink what they throw away and find ways to reuse, repair and recycle correctly.

“The goal is to turn waste into opportunity, ensuring valuable materials don’t end up in landfill,” says Lauren.

IF IT GROWS, IT GOES

Lauren says that, even when being mindful of minimising food waste, there will be leftover scraps.

“Instead of sending scraps to landfill, FOGO ensures they’re put to good use,” says Lauren.

When dumped at the tip, FOGO waste releases dangerous amounts of methane.

“By recovering food and garden waste, we can transform it into nutrient-rich compost that enriches our soil rather than contributing to harmful methane emissions,” says Lauren.

While innovation is valuable in effective waste management, we need to prioritise prevention – addressing the root cause rather than finding new ways to deal with the consequences.

Caption: The waste hierarchy is a useful tool

Credit: New Zealand Trade and Enterprise, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

“By embracing FOGO and having a ‘reduce waste’ mindset, we create a system where waste isn’t discarded – it’s given a new life,” says Lauren.

INNOVATE, ADAPT, OVERCOME?

Labs around the world are developing new technologies to deal with waste – from fungus that can eat plastic for lunch to bacterial enzymes that digest microplastics.

Some argue AI can save the day. Others, like our CSIRO, are creating compostable plastic, transforming waste into a valuable commodity.

But how far can innovation take us when we continue to consume at current rates?

“Refuse and reduce should be our first focus,” says Lauren.

“Reusing and repurposing then come into play.

“Ultimately, innovation should support reduction, not just better ways of managing waste.

“If we only focus on the latter, we risk treating the symptoms while allowing the problem – overconsumption – to persist unchecked.”