Water. It’s tasteless, colourless and odourless, but certainly not boring.

Wielding the power to both give life and take it away, it is necessary for all life as we know it.

Its chemical properties are all over the place, and it has a scary name: dihydrogen monoxide.

Although it may not bestow immortality, water is the true nectar of the gods.

Associate Professor Raffaella Demichelis from Curtin University explains some of water’s particularly odd characteristics.

TRIPLY WEIRD

Water is the only substance on Earth’s surface that exists naturally as a solid (ice), liquid (water) and gas (water vapour).

This is because of the Goldilocks-like nature of the forces at play, says Raffaella.

“Water is a bit special in the sense that, when water molecules interact [with each other], they don’t interact weakly enough for the forces to be ignored,” she says.

“But they don’t interact strongly enough for it to be a very strong solid.”

This makes it easier for water molecules to exist in all three states of matter among typical Earth conditions.

“The transitions of water happen in a range that, as humans, we can easily experience,” says Raffaella.

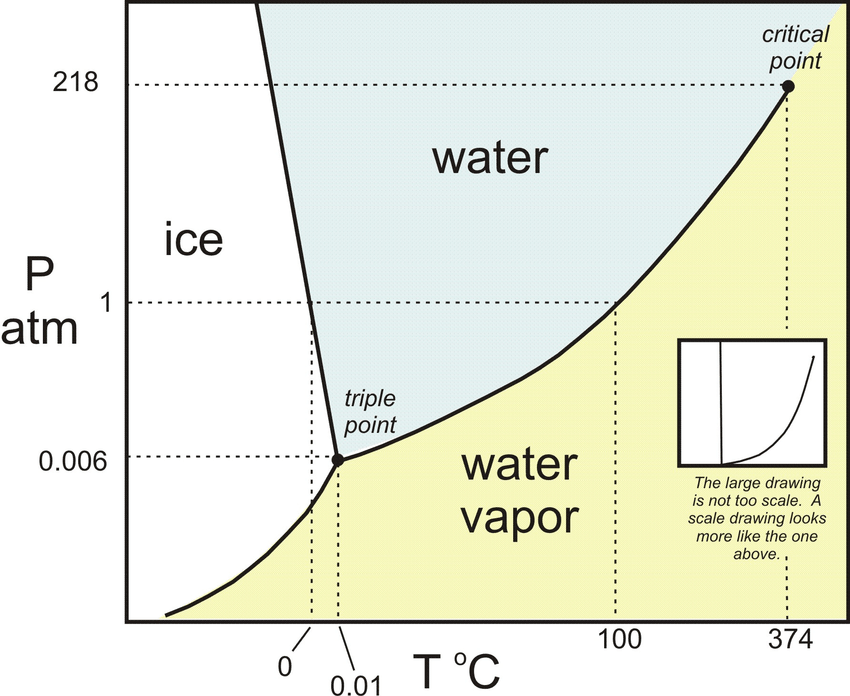

But water can exist in all three states at once, known as the triple point of water, where liquid water, vapour and ice coexist.

“It’s where the three phases are in equilibrium with one another. So by slightly changing the conditions, you can easily go from one to another,” says Raffaella.

Credit: Chitta Ranjan Das/ResearchGate

During a lightning strike, water can even naturally occur in the fourth state of matter, plasma. Talk about an overachiever.

ICE, ICE, BABY

Water does some particularly strange things when cooled.

Unlike most molecules, it doesn’t shrink when it freezes – it expands.

Below 3.98°C, water begins to interact with itself to form hexagonal-shaped clusters.

At 0°C, Raffaella says, “the molecules reorganise in a way that there is more space in between them when they are in the solid phase than when they are in the liquid phase”.

This is why soft drink cans explode in freezers.

As a result, frozen water expands its volume by up to 9%, creating another strange phenomenon.

“The molecules in liquid water are closer to one another. So if you take the same volume of water and ice, water is going to weigh more,” says Raffaella.

This is why ice floats – but not all ice.

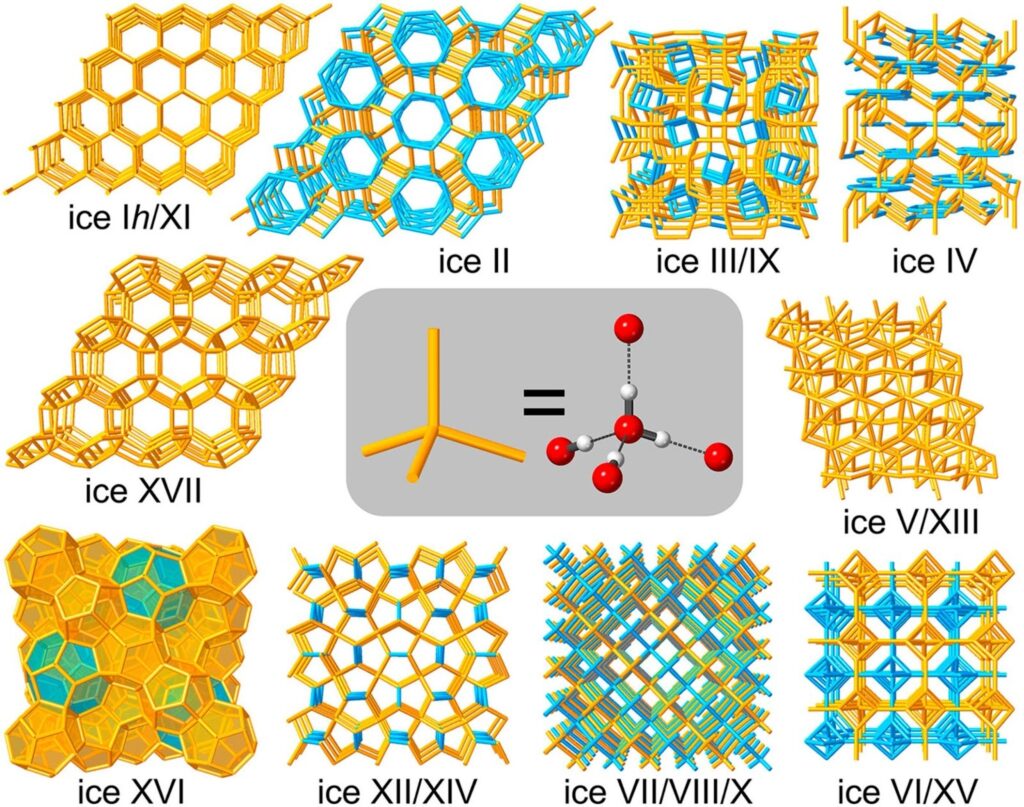

Ice doesn’t always crystallise in hexagonal clusters. It can form in many different structural ways, some of which have greater densities than water – so they sink.

Credit: Christoph G. Salzmann via AIP Publishing

These structures form under extreme pressures and temperatures. They can be observed trapped within diamonds or buried in icy gas planets like Uranus and Neptune.

Scientists like Raffaella use water in their crystal growth models, but given water’s complex properties, it isn’t always easy.

“Water looks very simple, but from a modelling point of view, it’s extremely complex,” says Raffaella.

“Water molecules are not standing on their own. They will constantly interact, they [will] constantly hold hands with other molecules.”

This hand-holding means water clusters can form in a seemingly infinite number of ways. With so many variables, creating an accurate model is no easy task.

Scientists from other fields experience similar problems when modelling water vapour.

WATER AND A WARMING CLIMATE

As the most abundant greenhouse gas, water vapour is the reason Earth is hospitable at all. It provides a nice cosy, atmospheric blanket to keep us warm.

Yet another reason to say thanks to water.

Establishing accurate water vapour models – which, like ice, are similarly plagued with water cluster confusion – will be an essential step towards combating the effects of a warming planet.

Water has many more incredible properties, but hopefully this article was enough to ‘wet’ your appetite.