This article is not about the trendy woolly mice or dinosaurs.

It’s about the ongoing, creeping extinction happening right here and now in Western Australia.

Australia has the worst mammal extinction rate in the world.

But why should we give a sh*t? After all, it’s survival of the fittest.

However, extinction isn’t just about one species vanishing quietly into the night.

It’s about the unravelling of an entire, interconnected system that could impact us all. Even your insurance premiums.

Surf

In 1994, then-PhD student Elizabeth Sinclair rediscovered an animal that had been thought extinct for most of the 20th century: Gilbert’s potoroo.

Since this discovery, Liz’s career as an evolutionary biologist has led her from land to sea.

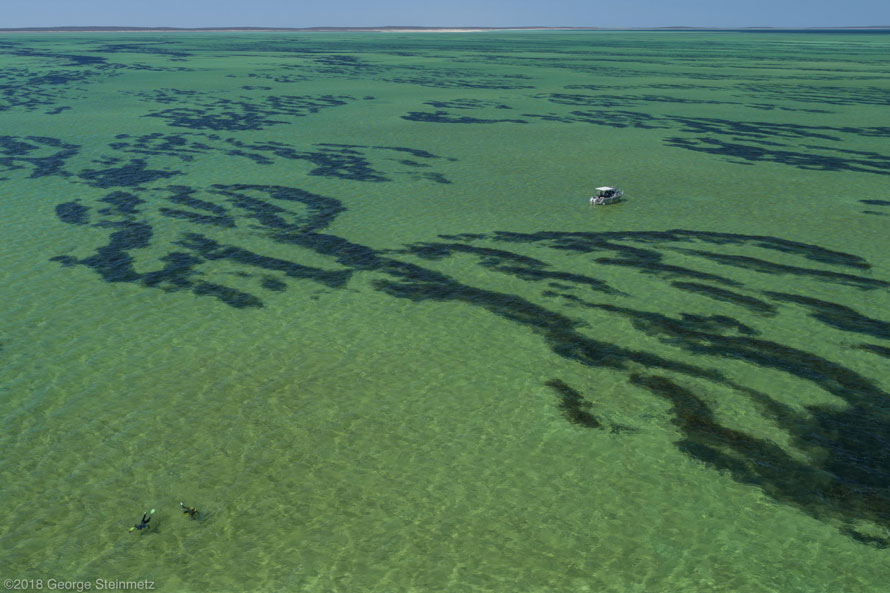

Her current research focuses on spatial patterns of genetic diversity and connectivity in temperate Australian seagrasses.

But Liz’s work with potoroos and seagrass shares a similar lesson: one extinction – or one species saved – can change an entire ecosystem.

“Every species within an ecosystem has a role to play,” Liz says.

“In 2011, we had a really bad heatwave over the summer. It knocked out about a third of the seagrass area in Shark Bay.

Credit: George Steinmetz, 2018.

“These lovely, underwater grasses do so many things.”

She explains that seagrass releases oxygen in the water, cooling it down.

Seagrass also slows down water movement, which reduces coastal erosion and removes carbon from the water.

“When we lost a third of the seagrass in Shark Bay, the visual change was immediate,” Liz says.

“But over the next 2 or 3 months and beyond, we saw the real impact.”

The loss of just a fraction of seagrass caused an entire ecosystem to change.

Fish that feed on seagrass were starving, and those that hid in them fled.

Reduced fish numbers meant less food for dolphins and cormorants.

Malgana people, the Traditional Owners of Gathaagudu/Shark Bay, had to stop harvesting fish, cormorant eggs and more for food, Liz says.

Many local fisheries were shut down because there weren’t enough fish to catch.

The ripple effect from the loss of one element in an environment – for both people and the planet – is not isolated to seagrass.

Turf

Despite many experts’ best efforts, Gilbert’s potoroo remains the world’s rarest marsupial, with the surviving 100–120 individuals living in Western Australia’s Great Southern region.

Like seagrass, Gilbert’s potoroo plays a unique role in its ecosystem.

Caption: Gilbert’s potoroo besties

Credit: Illustration by Richter in Gould’s Mammals of Australia (1863)

“You take one thing out and you go, yeah, it’s just a potoroo,” Liz says.

“But they all actually have an incredibly important role to play in these really intricate food webs and ecosystems.”

Gilbert’s potoroo is a fancy little fellow that subsists mainly on a truffle-like fungus.

“As they dig and forage, potoroos turn over the soil. If you take them away, that soil turnover doesn’t happen. Leaves and bark, and their nutrients, aren’t being dug into the soil,” Liz says.

“They also eat some berries. When they drop their little poos around the place, they’re spreading seeds and those plants germinate better.”

Pull one thread and the whole tapestry starts to fall apart.

What’s next?

Saving species like the potoroo isn’t cheap. Neither is planting seagrass meadows.

Caption: Designer woolly mice aren’t cheap either.

Credit: Colossal Biosciences

But we need to view conservation like the post office or public transport. It’s a service, not an expense.

Once a species is gone, no amount of cash can bring it back.

While we need science-backed conservation, we also need political will and public support.

“We need to understand that we are just one species that lives in the environment. It is not separate to us,” says Liz.

“Changes to our environment will affect us all.

“People are saying, ‘My insurance premium has gone up to $30,000’. Well, you probably live in a flood zone.

“If we start addressing climate change, the storms and this environment won’t be so extreme and we can solve this. And then you’ll be able to afford your insurance.”

Maybe Gilbert’s potoroo could even live to see another century.

Current conservation efforts are working, but there is always more to be done.

We need to give a sh*t about extinction to avoid crippling insurance premiums – if you aren’t dealing with them already.