The world is becoming a noisy place.

So much so that man-made noise is now considered a major global pollutant.

The impact of human activity was particularly obvious during the COVID-19 pandemic. When many of the world’s industries paused, global seismic noise was reduced by up to 50%.

We know that exposure to loud or prolonged noise can cause a range of health problems in people. But how does it affect our wildlife?

Grace Blackburn, a PhD candidate at UWA, set out to investigate how her local magpies are impacted.

She discovered that the smarter ones might be better equipped to deal with a noisier lifestyle.

NOISY NEIGHBOURS

Grace says research into the effects of man-made noise on wildlife has really expanded in the last couple of decades.

A wide range of animals have been shown to suffer from noise pollution. These include amphibians, arthropods, fish, mammals, molluscs, reptiles and birds.

“Many studies have found effects on the behaviour, communication and abundance of bird species,” says Grace.

CAUSING A RUCKUS

Noise is thought to impact birds in three main ways:

- By masking important communications and signals.

- By distracting birds away from important behaviours.

- By perceiving the noise as a threat, causing stress and behavioural change.

Grace’s team investigated the effects of noise pollution on Western Australian magpies around Perth Airport.

They found that higher levels of noise – above 50 decibels – decreased the amount of time the magpies spent foraging.

It also reduced their efficiency at finding food.

“[They] also vocalised less and had a lessened anti-predator response, or response to alarm call, when plane noise was present,” says Grace.

BIRDBRAINED

Most studies have focused on the effects on communities of animals rather than on individuals.

Grace’s study tested the cognitive performance of different magpies to see if individual intelligence was a factor.

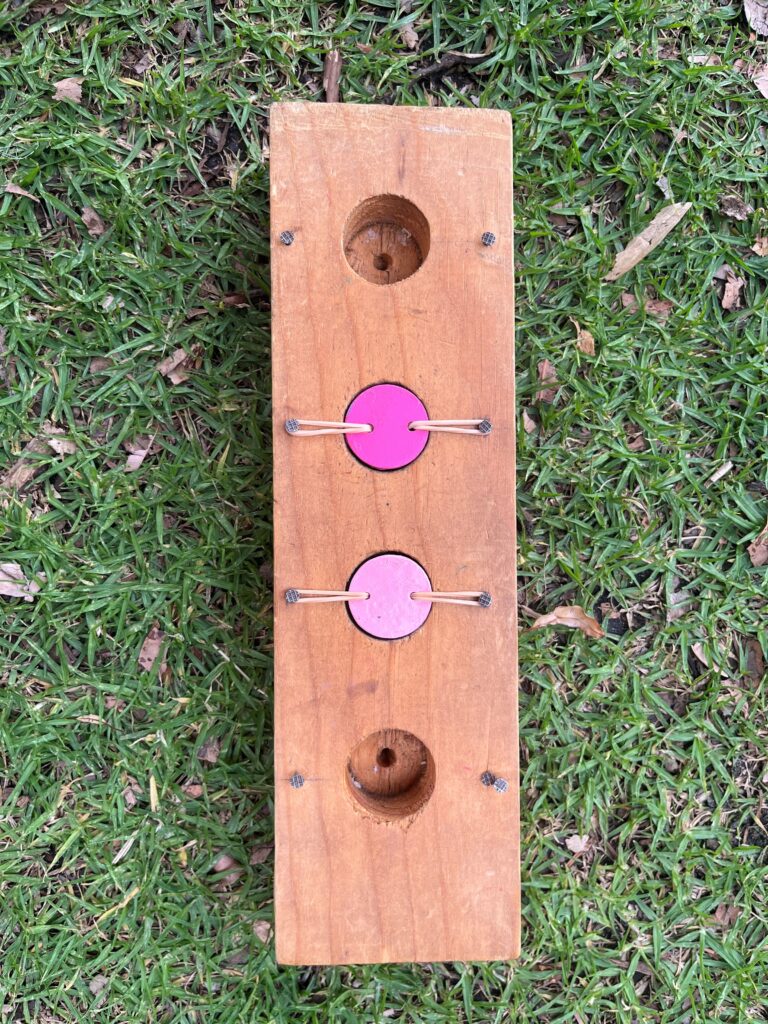

“The main [test] we used was an associative learning task. It requires birds to learn an association between a colour shade and a food reward,” she says.

Food was placed in wooden wells behind a certain colour of lid. The team scored how quickly each bird learned which colour held food.

“Birds that have better associative learning abilities will learn the task faster and have a lower score,” says Grace.

STREET SMARTS

The magpies that scored better at the learning task turned out to be less impacted by a noisy environment.

“[They] were better at maintaining their normal response to alarm calls even when noise was present,” says Grace.

This is the first documented evidence of a link between cognitive performance and noise response. Grace’s team isn’t sure exactly why this is the case yet.

“It could be because they are able to form stronger associations between alarm call and threat,” says Grace.

“Or [they] may be better at processing and responding to multiple sources of acoustic stimuli.”

TWO BIRDS WITH ONE STONE

Grace says noise pollution has the potential to drastically affect magpies’ lives.

“[It’s] already affecting how much food [they] can locate and eat, and how well they respond [to predators],” she says.

Many studies suggest the negative effects of noise are shared by most species rather than some being more sensitive to it than others.

A better understanding of these effects could therefore help us to protect all affected wildlife.

In the meantime, Grace suggests that embracing a quieter lifestyle on an individual level can help too. This could be anything from riding a bike to work to planting more noise-absorbing plants.

Humans and animals alike could benefit from a little more peace and quiet in our lives.