If you’ve got a big rock with a little bit of metal in it, how do you get it out?

Most of the time, you would smash it and dunk it in powerful acid until everything dissolves, then sieve out the metal.

But what if that big rock is thousands of kilometres across? That’s a lot of acid to buy. Not to mention how detrimental it could be for the environment.

What if you could get someone who could make acid where it was needed, without compromising the environment? Like a worker … who gets paid in water.

The smallest employee

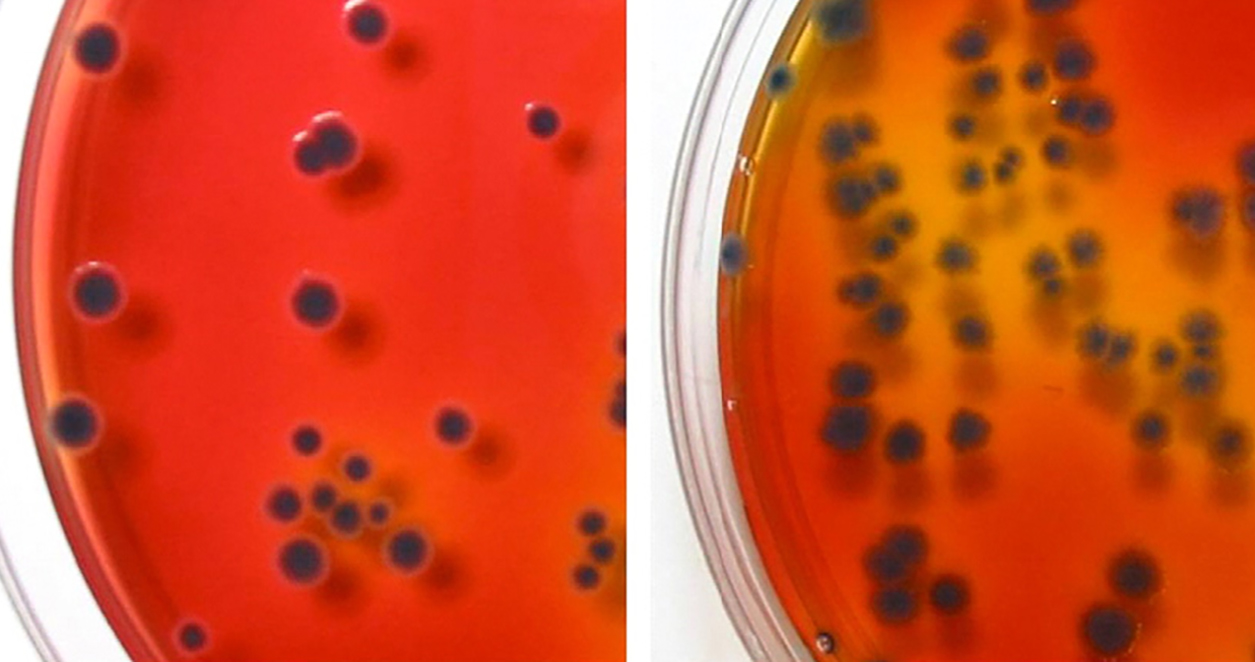

Bioleaching uses bacteria that make their own organic acids to break down minerals. As the bacteria feed, they expose rare-earth metals, which run off in the water fed through the rock.

Because the valuable metals are in the run-off, the bioleaching system is contained, meaning less pollution than traditional methods.

Professor Elizabeth Watkin is a researcher in molecular microbial ecology at Curtin University. She studies how tiny things like bacteria, viruses and fungi interact with the environment.

“We were looking at a phosphate-based rare-earth ore, monazite. It’s critical to today’s society because it contains cerium and lanthanum,” says Elizabeth.

Phosphate is an oxygen-laden mineral found in many foods.

Lanthanum alloys and cerium are used in lights, batteries and medicine. These rare-earth metals are trapped inside rocks, surrounded by phosphate molecules, which the bacteria eat.

“These organisms are already used widely in agriculture to make phosphate available in the soil to encourage plant growth. We apply that agricultural knowledge to these minerals,” says Elizabeth.

“We’re actually one of the first groups to look at rare-earth bioleaching. It’s us and a group at UC Berkley in the United States. We’ve proven it works, and now we’re reaching out to engineers to try and incorporate it into their mining operations.”

Bacteria on acid

While bioleaching for rare-earth metals is new, the method is already being used to mine copper in Western Australia and around the world.

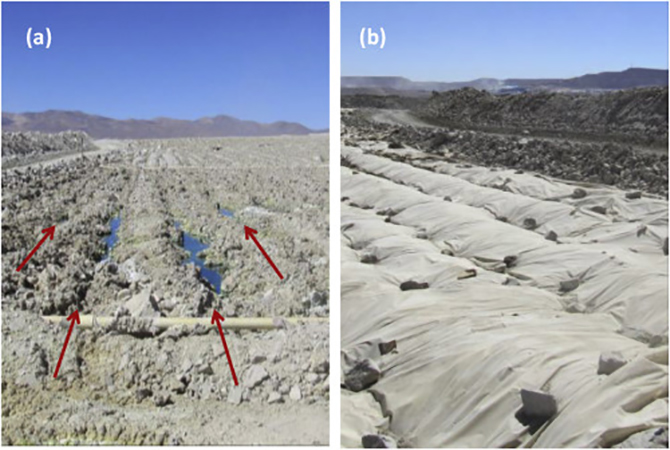

These bioleaching piles are giant living reactors that break down rocks for energy. They can be thousands of kilometres across.

Water is drip filtered through the rock, allowing the bacteria to grow and letting the metals collect in the run-off.

One local species used for bioleaching was actually found in an old open-cut coal mine in Collie, Western Australia.

While the acidic, toxic environment doesn’t seem like a cosy home, it was an all-you-can-eat-buffet for Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius.

These bacteria have evolved to use those elements as part of their metabolism – much like the mineral-munching microbes found around volcanic vents under the sea.

“In this space, we work with iron and sulphur-oxidising bacteria,” says Elizabeth.

“When iron and sulphur are oxidised, they release electrons which the bacteria use for ATP [energy] production.”

In the wild, these bacteria are harmful, releasing their acid into nearby water systems. But when controlled, they may actually prove more environmentally friendly than the artificial acids whose jobs they’re taking.