Bee venom contains proteins with anti-inflammatory, antiviral and antibacterial properties. It’s been used in therapeutic and cosmetic products, such as joint and muscle pain relief cream and skincare products, for years.

Now, a WA study is investigating how environmental factors affect bee venom composition. The aim is to develop a consistent, certifiable product for the lucrative bee venom market.

Sting like a bee

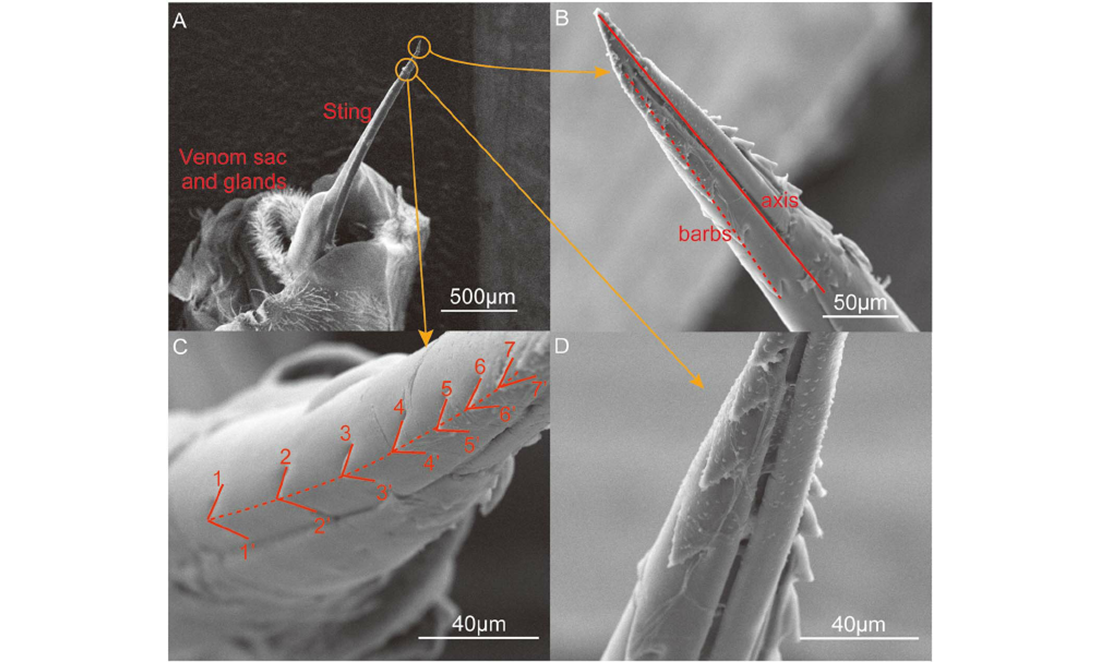

Harvesting bee venom without harming the bee is a tricky task. Nestled in a cavity at the end of its abdomen, its stinger is attached to three lower abdominal segments by delicate membranes.

When a bee stings, it jabs its barbed stinger into the skin to inject venom. This action rips out much of the bee’s digestive tract, as well as the venom gland.

Its body torn apart, the bee dies soon after.

Dr Daniela Scaccabarozzi is a pollination biologist and ecologist at Curtin University and ChemCentre. She was part of the research team that worked with commercial apiarists to examine how diet and lifestyle affects the bee venom volume and potency.

The buzz about bee venom

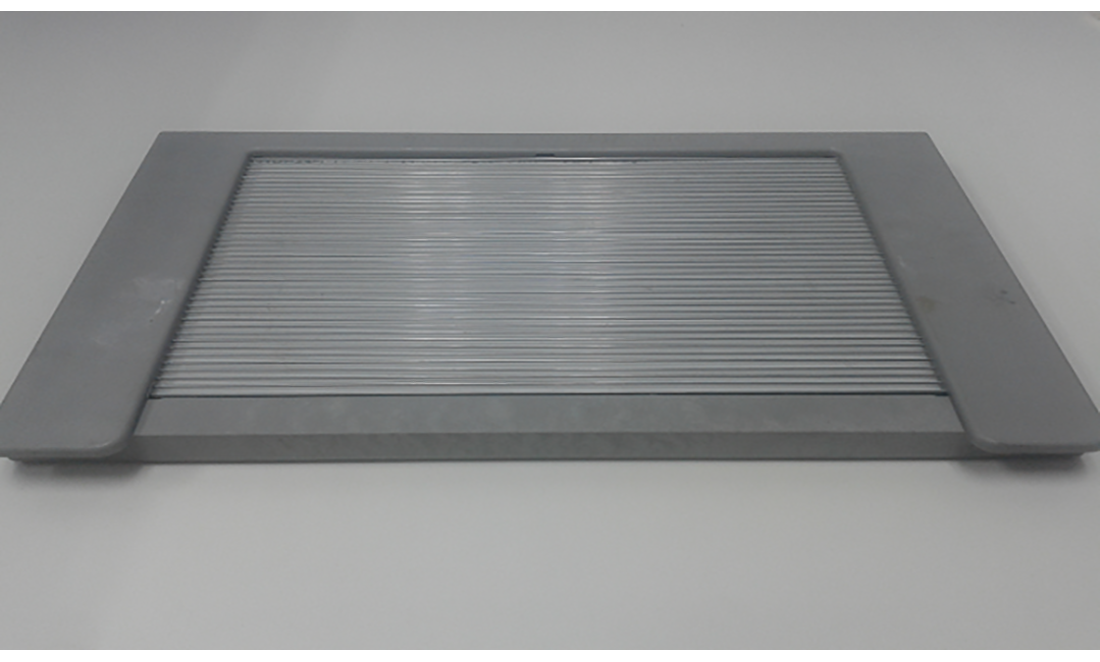

To collect the venom, they placed an electrified plate inside the hives. It gave a low-voltage zap to the bees, which responded by stinging it. The plate’s surface was made of glass. Instead of the bee’s stinger being ripped from its body, the residue was left on the surface. This way, the bees were unharmed.

“The venom is pretty stable,” says Daniela. “The proteins won’t change their composition and it dries rapidly. But we kept it in the freezer and handled it in sterile conditions so there was no contamination.”

The crystallised white powder is collected then dissolved and purified. It is broken into fragments called peptides. Then liquid chromatography separates the proteins by size. The peptides are vaporised and shot with an electron beam changes their magnetic charge. A process called mass spectrometry tells the researchers each peptide’s mass-to-charge ratio, which acts like a barcode to identify them.

They’ve got 99 proteins

The team identified 99 different proteins in the bee venom samples collected from colonies between Chittering and Harvey. That’s more than three times the 30 individual proteins previously identified. Bees with an aggressive stinging action produced a more-complex protein-rich venom.

“We found, in high temperatures, bees produced less venom and docile bees produced less, but other management factors like diet didn’t really affect the volume of venom,” Daniela says. “Flowering stage affected the proteins present.”

It might be surprising that the Western honeybee has such poorly understood venom. We domesticated the species over 9000 years ago, breeding them to be more docile.

Unbeelievable potential

When you’re stung by a bee, the proteins phospholipase and melittin work together to cause pain and inflammation. With bacteria becoming antibiotic resistant, antimicrobial peptide treatments could help fight superbugs.

While there are no approved clinical uses for bee venom, the research is promising. It’s shown encouraging results for treating neurological issues like Alzheimer’s, while WA researchers have shown it can kill aggressive breast cancer cells.

One study found bee venom could even be used as a potential SARS-CoV-2 treatment. But much more research is required in this area, and vaccines remain the most effective way to prevent severe infection.

While it’s early days, bee venom could be lucrative for beekeepers. Bee venom fetches up to US$300 per gram, compared to the US$4 per kilogram beekeepers make on honey. And that’s not to mention the impact pesticides, global warming and land clearing are having on global honey production.

So where does it leave us? Daniela says there’s more work to be done. “We still need to understand how to shape the composition and optimise the harvest and scale it so production is really reliable and beneficial for human health,” says Daniela.

The project was managed by ChemCentre with Australian Natural Biotechnology acting as an industry partner.