If future trials also prove successful, the tool could transform breast surgery theatres across the globe.

Improvements in breast cancer detection mean more patients are having tumours removed, rather than undergoing full mastectomies.

REMOVING TUMOURS

To do this, doctors remove the tumour, plus a margin of healthy flesh to ensure the tumour does not return.

Pathologists then examine the removed flesh in a process that takes several days.

If they discover more malignant tumour near the edge of the lump removed, the patient must return to the operating table. This happens in about a quarter of all cases.

A NEW IMAGING TOOL

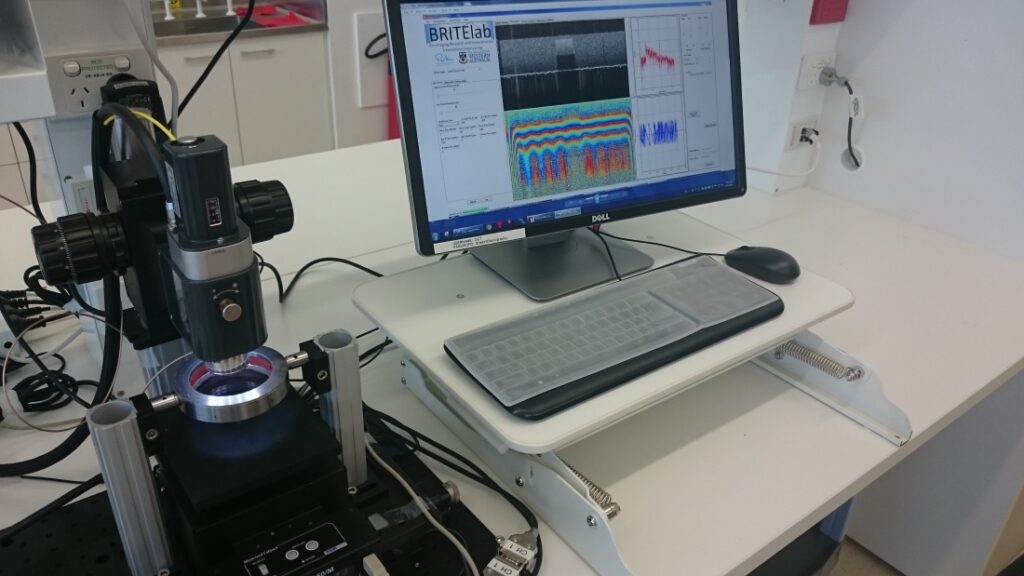

The new optical imaging tool will enable surgeons to examine the removed flesh while the patient remains on the operating table.

If the tool shows malignant tissue near the edge, the surgeon can remove additional flesh in the one procedure.

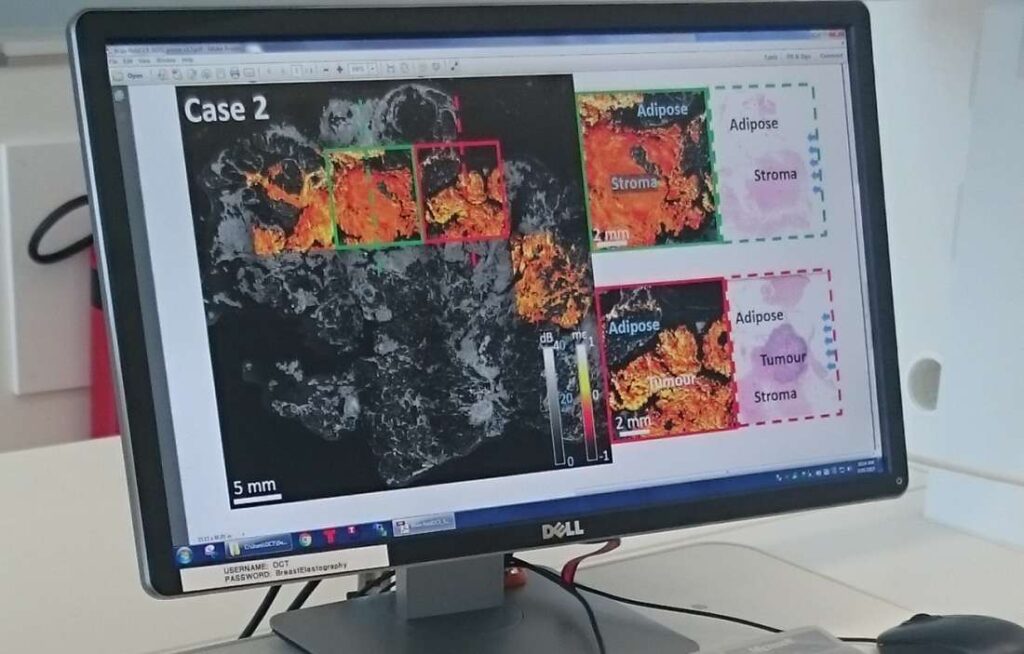

The process is called ‘optical coherence elastography’. It works similar to ultrasound, only it uses light reflection to paint a picture inside human flesh, rather than sound.

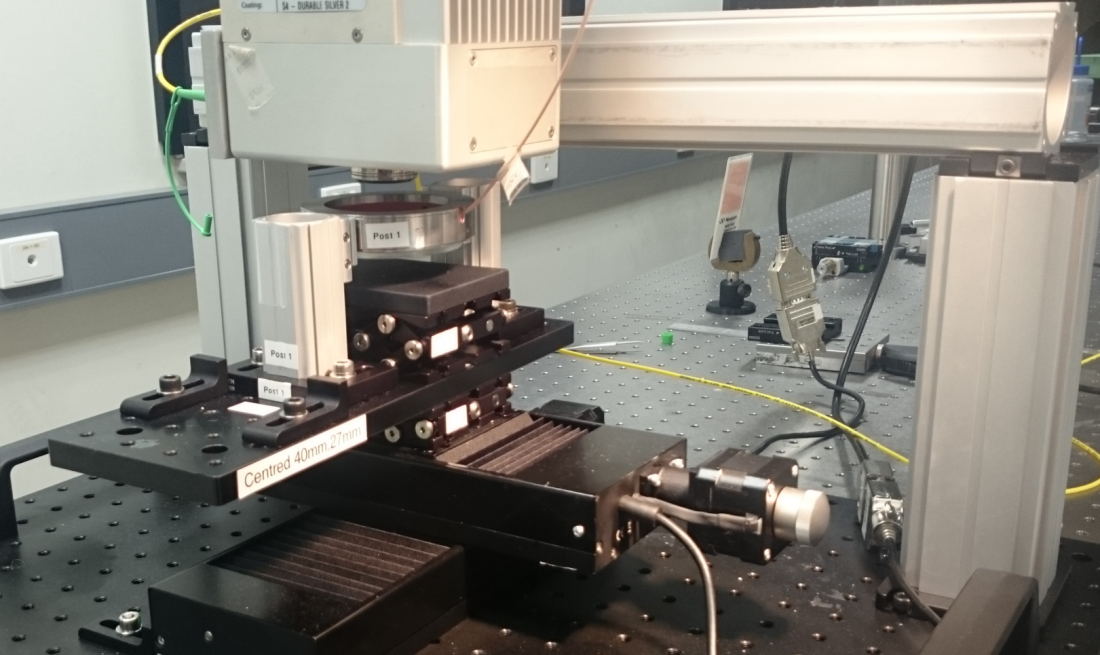

The benchtop system directs infrared light into the flesh and records the reflected light to generate a 3D, high-resolution image.

The system also measures the mechanical properties of the flesh. It achieves this by compressing the flesh during imaging and tracking the movement at each pixel.

Soft regions will compress more than stiff regions. Combining the mechanical properties with the optical properties increases the ability of the system to detect malignant tumour.

DETECTING MICROSCOPIC REGIONS OF TUMOURS

UWA PhD student, based at The Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research, Wes Allen says surgeons rely on touch to find the hard flesh that may be cancerous. But the new imaging technique is able to detect microscopic regions of tumour the finger isn’t sensitive enough to feel.

With positive results from a preliminary study of 78 scanned specimens, Wes and a team of engineers, surgeons and pathologists will now embark on a large-scale trial involving hundreds of cases.

If successful, the trial will pave the way for surgeons to use the tool in theatres worldwide.

“It’s really exciting,” Wes says. “We hope that there will be one of these machines in every breast surgery theatre in the world.”

In a related study, scientists are also now working on developing the machine into a hand-held probe. Surgeons could use the probe to scan flesh inside the body cavity during surgery.