Do you know what most people do all day? Where do they go, what do they eat, who do they talk to? Well, if you think it’d be hard to track a person’s every move, imagine tracking the behaviour of a wild animal, in the ocean.

The life of most marine animals is a bit of a mystery—it’s pretty hard to track any animal cruising through the ocean. But now, Murdoch University fish biologist Lauran Brewster and her team have found a neat way to get an up-close view of the day-to-day activities of a wild marine species.

“It can be very hard to study wild animals in their natural environment, particularly when they travel long distances or live in an environment that makes them hard to observe,” says Lauran.

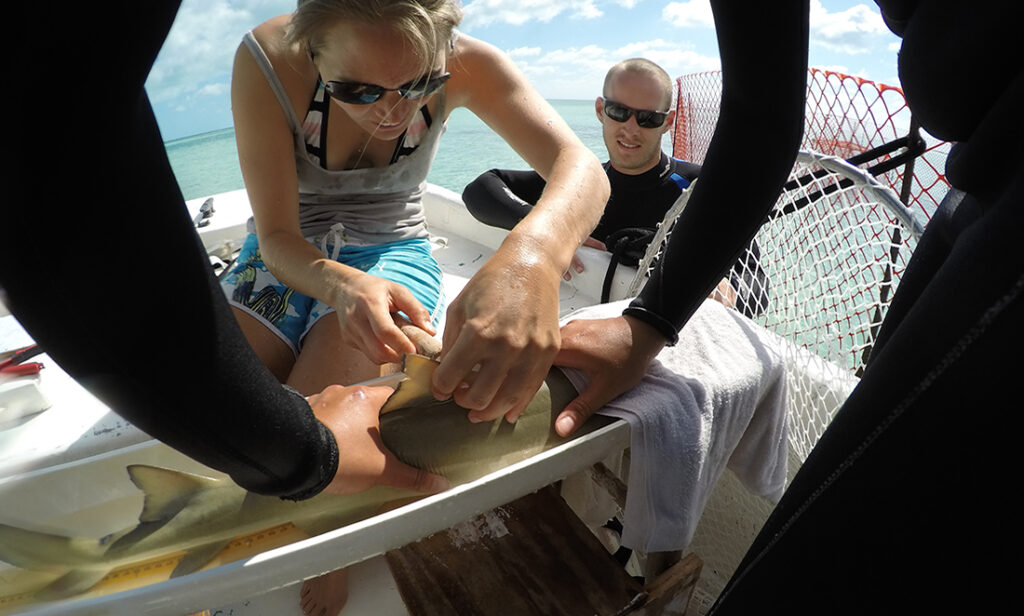

In the new study, Lauran attached a Fitbit like device, known as an accelerometer, to the fin of several lemon sharks to learn about their daily habits.

Tracking a lemon shark

Lemon sharks are found in the Americas and West Africa, spending most of their time in shallow ocean waters. While juveniles are fairly well studied in enclosed conditions, it is not so easy to study them in the wild. They spend most of their day in hard-to-reach places, so it’s hard to know what they are up to throughout the day.

“This has prevented scientists from determining what these animals do on a daily basis and how long they spend performing different activities,” Lauran says.

“Accelerometers (like those used in wearable Fitbits) can help us overcome this hurdle. They collect body movement data from these animals, which can then be used to calculate energy expenditure and be classified into different behaviours,” she adds.

Lauran started by tagging semi-captive sharks and watching their behaviour. The data obtained from these gizmos was analysed through a complex statistical approach known as machine learning.

“Machine learning is a model that learns patterns in data and can be used to identify similar patterns in new data and make predictions from it.”

“Very basically, machine learning is a model that learns patterns in data and can be used to identify similar patterns in new data and make predictions from it,” says Lauran.

You might not know it, but we are all exposed to the workings of machine learning every day.

“For example, when Facebook recognises people to tag in a new photo or gives you a recommendation for your next Netflix series based on your previous viewing history, that is the product of machine learning,” she adds.

After developing this approach on the captive sharks, Lauran was able to classify five basic behaviours.

“The model identified five different behaviours for lemon sharks, like swimming and resting. Also, successful prey capture (represented by the shark shaking its head from side to side), burst swimming and chafing behaviours, where the shark performs a barrel roll movement to scratch its back,” says Lauran.

A day in the life … of sharks

In her study, which took place in the Bimini Islands, Bahamas, Lauran tagged a total of 24 wild sharks.

Tagging the sharks was the easy part, as juvenile lemon sharks are commonly found around the area the researchers were studying. The tricky part was getting the data.

“The hardest part is finding the shark again to retrieve the tag so we can download the data,” says Lauran.

Twenty were recaptured, which provided the data for the study.

After analysing the data from these wild sharks, Lauran found that these sharks hardly get any rest, especially in summer.

“The time spent on different activities varied dramatically. For example, they spent, on average, 1% of their day resting during the warmer months and 10% during the colder months,” says Lauran.

The data also revealed some details about their daily activities. For instance, these sharks prefer to capture prey in the early evening and don’t seem to like eating during high tide. The data also showed that they eat more when the water is warm.

This information will improve our understanding of the ecology of this species and may also help us understand how human activity is affecting the behaviour of these elusive species. However, so far, the data collected for these sharks is limited to pristine environments, but a great deal of the ocean is far from pristine.

Now, Lauran plans to study the behaviour of sharks living in areas affected by human development.

“We have been able to determine the fine-scale activity budget of a wild shark species here in pristine conditions. We can compare it with the activity of other lemon sharks inhabiting waters degraded by human development as a means to assess the risks associated with coastal development and establish how to manage the impact development has on coastal species,” says Lauran.

With this information, Lauran hopes to understand how this species responds not only to human disturbance but also to changing environmental conditions such as temperature change.