It’s thought to be the oldest biotech process in the world.

For thousands of years, brewers have fermented grains to produce one of humanity’s favourite drinks.

Now, researchers are taking a high-tech lens to this ancient process.

They’re using a precision technique usually reserved for medical research to study the proteins in beer.

Packing the protein

ECU Professor Michelle Colgrave is an expert in proteomics—the study of proteins.

She has examined proteins in more than 100 different beers.

“As I’m travelling the world, I often collect beers, or people send me them for testing,” Michelle says.

And while you may have heard the joke that there’s a steak in every Guinness, there really are a lot of proteins in beer.

Michelle says your pint could contain hundreds of different types, and they have a big impact on your drink.

A modern take on an ancient tradition

“Much of the flavour that’s present in beer is either coming from the barley, or it’s coming from the hops,” she says.

“It’s the protein components in the barley that are responsible for some of that flavour.”

Michelle says proteins also interact with other small molecules to produce haze, which is generally undesirable in a lager.

And proteins are implicated in mouthfeel and foam stability.

“If you want the head on the beer, you need to have those proteins”

Crafty brewers and their craft beers

According to the German beer purity law Reinheitsgebot, there should only be four ingredients in beer—barley, hops, water and yeast.

But craft brewers are increasingly experimenting with weird and wonderful ingredients.

Michelle says different styles of beer can be created by swapping barley for other grains.

“Obviously there are wheat beers, and there are many other beers that are made from different, alternative grains,” she says.

“So you can get beers that include corn, millet, sorghum and others.”

Other additives include spices, honey, fruit, coffee and chocolate.

In WA, South Fremantle Brewing recently collaborated with Eat No Evil to produce a saltbush and pepperberry pilsner.

Although one Oregon brewer might have taken ‘eat local’ a bit too far in producing beer from yeast discovered in his own beard.

Safe, sustainable and delicious

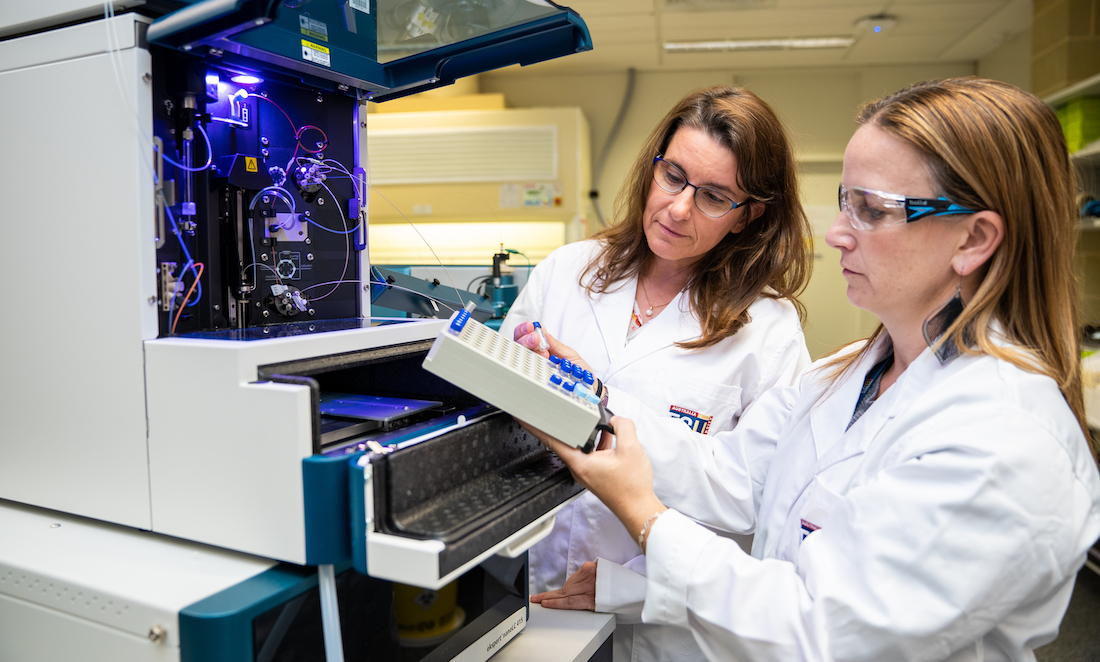

Michelle and her team are using a technique called mass spectrometry.

It’s a super-precise way of measuring proteins that’s usually used for medical or biotech research.

Michelle says the technology can help to make sure food is safe and sustainable and tastes good.

“We seek to explore how new varieties of wheat and barley that you might use in beer will be better suited to our changing environment,” she says.

“Then if we use these better suited [grain] varieties, we need to know how they actually stack up when we’re looking at the finished product.”

I’ll cheers to that

So what drink’s on the Colgrave menu this summer?

Having tested everything from boutique craft brews to beers that even the most hardened bogan would turn their nose up at, Michelle doesn’t hesitate in naming her favourite.

“If you ask the husband, he’ll probably go for a chocolate malt, so a dark ale,” she laughs.

“But I’m more of an IPA drinker.”