You may have recently seen some videos of dogs and cats communicating with their owners on TikTok and Instagram by using a collection of buttons on the floor.

Like Justin Bieber, the cat, telling his owner he was cranky about his late breakfast by stepping on the buttons for “food” and “mad”. (A typical cat vibe.)

As it turns out, some of these furry animals ‘voicing’ their thoughts and feelings are part of a global citizen science project.

(T)raining cats and dogs

The idea for FluentPet came from the world’s first video game console for dogs.

“We found that dogs were able to push the concept,” says Leo Trottier, the founder and CEO of FluentPet.

“They could recognise and react to different stimuli to communicate with us far better than we imagined.”

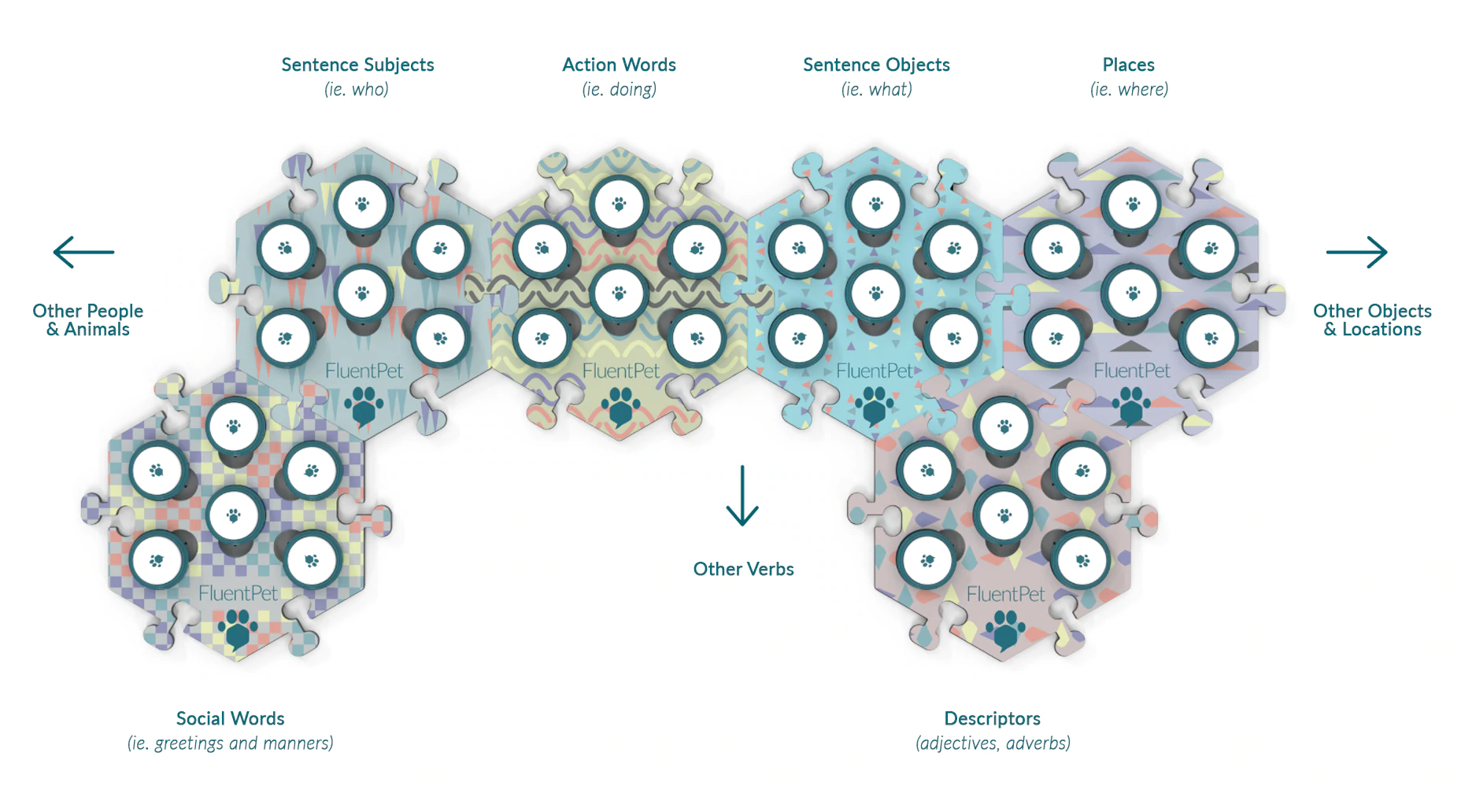

The team at FluentPet used findings from cognitive science and speech language pathology to design a system called HexTiles. You can think of it as a sound-emitting keyboard or soundboard.

“Our HexTiles feature an array of programmable buttons arranged in a hexagonal format with colours and shapes suited for non-human eyes. They allow animal companions to associate specific activities and things with a particular button that, when pressed, makes the sound of a word that corresponds to it,” says Leo.

Among other things, the HexTiles team were inspired by the Fitzgerald Key, a tool developed by Edith Mansford Fitzgerald to help hearing-impaired students construct grammatically correct sentences.

Questions for our furry friends

FluentPet has partnered with the Comparative Cognition Lab for TheyCanTalk – a global citizen science project exploring animal communication via soundboards.

The study involves more than 5000 dogs and 800 cats from 48 countries, with owners regularly providing data via questionnaires and surveys.

Dr Federico Rossano, the founder of Comparative Cognition Lab and a cognitive science professor at the University of California San Diego, is leading the project. And according to him, TheyCanTalk is currently the largest citizen science study on animal communication.

Is it really pawsible?

Federico was initially sceptical about the idea of dogs using a soundboard. However, after 18 months of collecting data from around the world, his attitude has changed.

“Once you start spending one and a half years looking into the data and hearing reports and watching videos, you start realising that there’s much more happening that you didn’t necessarily expect,” says Federico.

And as it turns out, using soundboards to communicate with animals is so much more than just training them to memorise words.

Through the TheyCanTalk project, Federico has observed that, in a household with multiple dogs, the dog that is more proficient with the soundboard often talks for the other one. For example, one dog might tell their owner that the other dog wants to be let inside.

"It reveals an orientation towards their social mind, that is beautiful."

It may come as no surprise to dog owners that some of the words most commonly ‘said’ by dogs were the names of people or other pets in the household.

“So they’re talking about others. They’re social creatures, and we keep forgetting that,” says Federico.

“They also talk about how upset they are about not getting what they want or how excited they are about something happening.”

Going further than before

Federico’s research picks up from where previous animal language research left off. Past studies generally involved training an animal in an artificial setting for 8 hours a day. Results were largely measured by the number of words memorised rather than how the animals ‘voiced’ their thoughts and feelings.

“So basically, it’s the difference between studying a dictionary and looking at communication,” says Federico.

According to Federico, we’ve “missed the boat” when studying animal communication.

“Not just the ability to read human emotion, but their ability to experience emotions and communicate those emotions to each other and to us,” he says.

In TheyCanTalk, Federico and his team are focusing on the thoughts and feelings of the participating dogs and cats instead of just their ability to memorise. And they’ve been able to collect thousands of data points from all over the world because it’s far easier for humans to train their pets at home than scientists training them in a foreign lab setting.

According to Federico, studying animal communication in a natural setting makes more sense because cats and dogs are cognitively comparable to 2-year-old children.

Where to from here?

Federico says the next stage of the study involves cameras being installed in participants’ homes to record and confirm the data.

The team will first use machine learning to analyse these videos. Then they’ll follow up to confirm that a citizen scientist’s report about their pet’s understanding of a certain concept is in fact true.

For Federico, the long-term goal is changing the way we treat animals.

"Being able to find a way to convey [their emotions] could be huge in terms of animal rights and animal welfare."