Microscopes are more than an essential tool for scientific research – they can make the seemingly mundane appear magnificent.

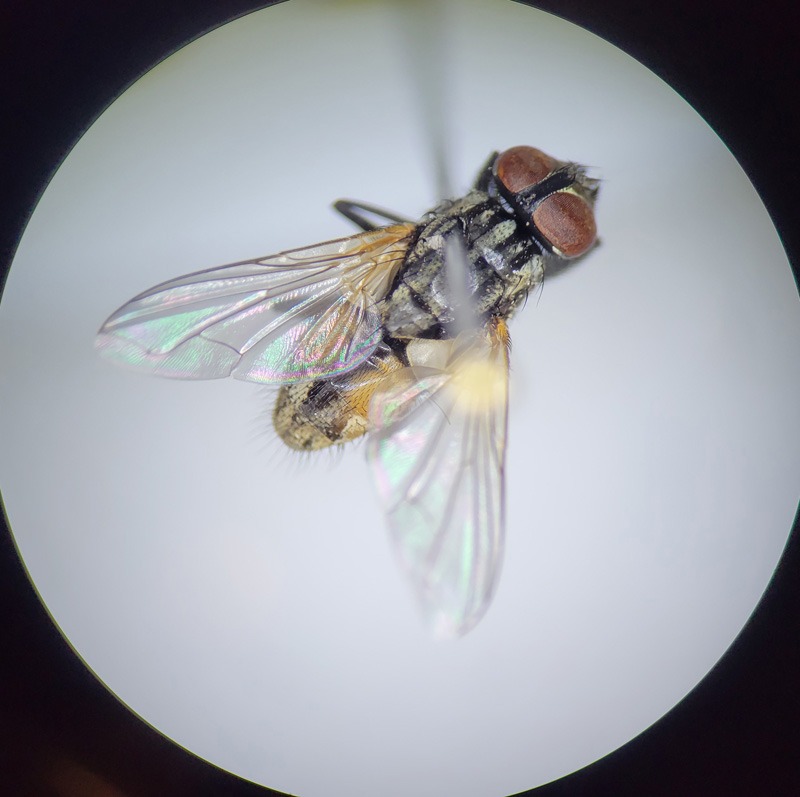

Take the humble house fly.

An irritating insect that appears as a blur to the naked eye can become fascinating once you add some magnification.

A NEW PERSPECTIVE

The first microscopes had a single lens and were really just glorified magnifying glasses.

In the late 1590s, Zacharias Janssen invented the first compound microscope, providing a new perspective of the world.

These initial compound microscopes focused light through two precisely ground glass lenses and could achieve an impressive (at the time) 3–30x magnification.

As lens-making technology improved, so did microscopes’ power, and their adoption within the sciences increased.

A new form of scientific enquiry was born.

Credit: Matt Pelikan

MORE THAN MEETS THE EYE

Modern microscopes can achieve far greater resolution than Janssen’s and have a range of specialities, including viewing living cells, photographing 3D samples and identifying minerals.

We can compare the resolution by taking another look at our house fly.

At 10x magnification, the intricate pattern of a fly’s compound eyes is in focus. At 100x, the hairs upon its pearlescent wings. At 400x, the bacteria coating its proboscis (sucking mouthpart) are visible.

But 400x is child’s play.

Credit: Jean Beaufort

Modern compound microscopes can magnify a sample up to 2000 times. Under this level of magnification, the internal workings of individual cells in the fly’s brain become perceptible.

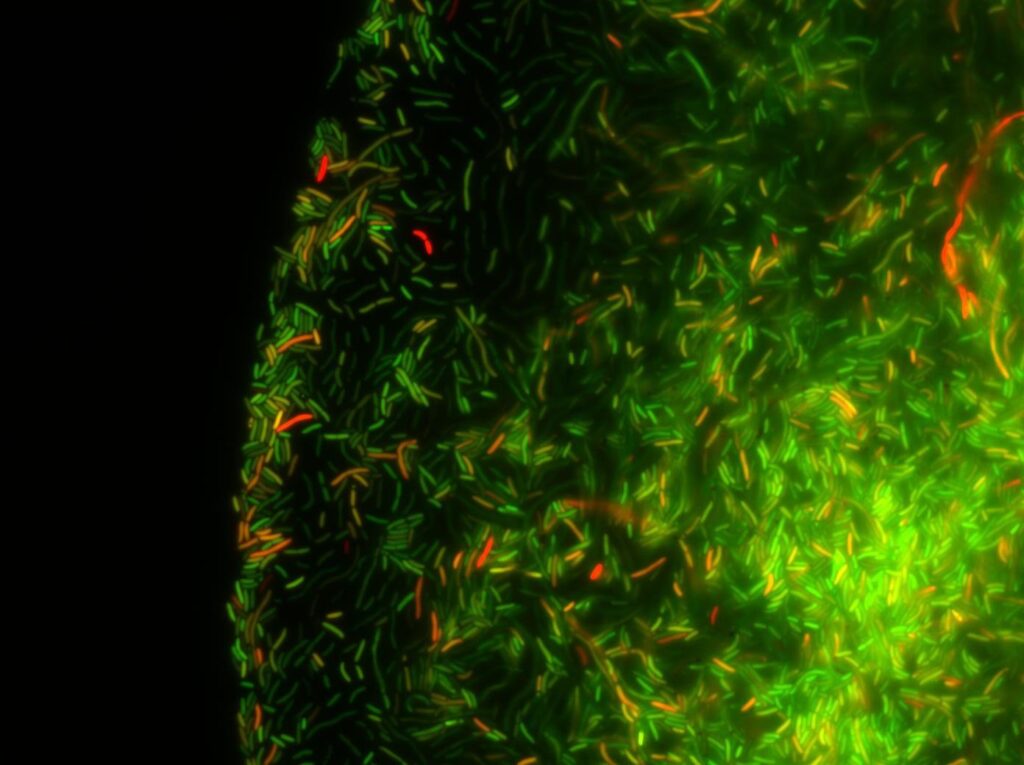

Another kind of light microscope is the fluorescence microscope.

It uses a high-intensity light source to excite fluorescent compounds, called indicators, which are added to samples.

These indicators can be tailored to highlight points of interest within a cell.

This was a game-changer for biologists, making it easier to understand cell physiology. It also creates striking imagery.

Credit: Pakpoom Subsoontorn, CC BY 4.0

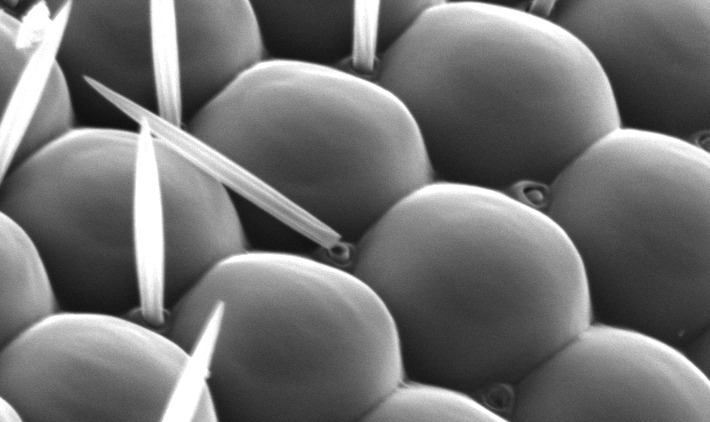

ELECTRON MICROSCOPES

Instead of using light, electron microscopes scan a sample with an electron beam and detect how electrons reflect or pass through a sample to create an image.

This allows scientists to ‘see’ things less than a nanometre in size – like atoms – magnifying structures by up to 50 million times.

There are two main types of electron microscopes: the scanning electron microscope (SEM) and the transmission electron microscope (TEM).

SEMs can show surface textures, like a fly’s face, in intricate and somewhat disturbing detail.

Credit: CC BY-SA 2.5

In TEM, electrons interact with a sample as they pass through it on their way to a detector, providing vital information about its fundamental structures.

With TEM, scientists are able to see the molecules and atoms that make a fly a fly.

TOUCHY FEELY MICROSCOPES

Microscope technology isn’t limited to light and electrons.

While not appropriate for all fly analyses, ‘touch’ based microscope technology has advanced areas like materials science.

An atomic force microscope (AFM) provides an image by getting interactive. A very pointy, microscopic metal tip is dragged along a sample, translating the touch into an image.

AFM provides a high-resolution topographic map of a surface.

The newly developed GelSight microscope delivers magnified data by squishing a gel pad onto the sample. (Probably a bit messy to try with our fly.)

While hundreds of years have passed since the invention of the microscope, the most significant advancements have occurred in recent decades.

There’s no knowing what breakthrough will be next, as microscopes continue to reveal more about the world – and often overlooked insects like the house fly.