Since its invention, photography has been our window to the past. Photographs freeze moments in time so we can go back and remember. We use them to tell the stories of our history.

But for many Indigenous communities in WA, important moments in their history were kept out of reach.

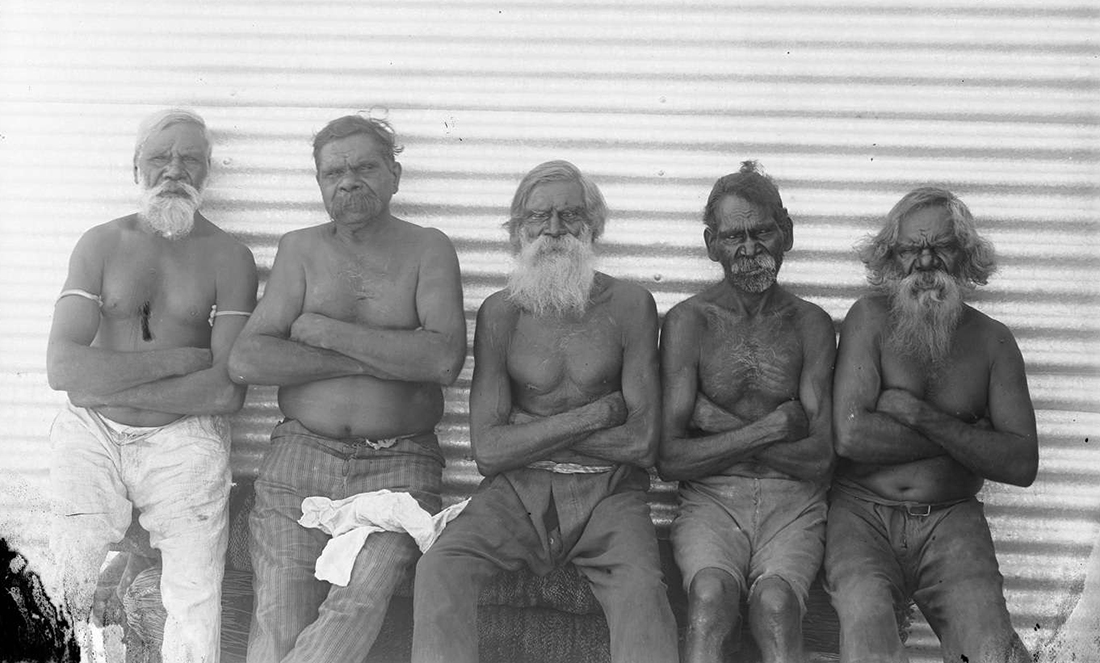

In the early 1900s, the government took thousands of photos of Aboriginal people, but stored away in archives, they were never seen by the people in them or returned to their families.

That’s why the State Library came up with Storylines—an online image database connecting Indigenous people with their history.

Looking for a better way

Damien Webb is the Indigenous Liaison Officer at the State Library. It’s his job to connect Indigenous West Australians with the library’s heritage collections.

But that’s a hard job to do within four walls. Many Indigenous communities live in remote or regional areas. And WA is a big place.

So how do you reach the largest group of people in the smallest timeframe?

You go digital, of course.

A software solution

Storylines uses the software Keeping Culture as a central database for photos. Think of it like a big, online photo album.

The library wanted to make it easy to access, so all you need is an internet connection. A whole generation of Aboriginal history is then only a click away.

You can search by names or places or just browse through the library’s collections.

Anyone can submit information about the images, such as the names of the people in them. The library can then verify it and update Storylines and their archives.

This is how the State Library have been able to identify thousands of photographs.

“Community feedback has been incredibly overwhelming. We’ve identified something like 1000, nearly 2000 photographs that before we started this project had no idea what the photograph was,” Damien smiles.

“It was just a picture that would be captioned ‘Natives. Kimberley’, whereas we now know the names of all four men, how they were connected, what they were doing in this photo [and] what happened after the photo.”

Writing a new story

The State Library planned to return photos once they were identified, but they found that, as people learned their stories, many were eager to share them.

Pearl Ashwin got in touch after discovering a photo of her 16-year-old self was in Storylines. She was one of the first Aboriginal registered nurses in Meekatharra. Her photo shows her accepting an award for Civic Achievement.

As a pioneer in her field, she had always been a part of WA history, but knowing her story was being told made her feel like she truly was.

“Her main takeaway from that was that she felt as if she was part of Western Australian history now—that she was part of the WA story,” Damien says.

“I think it’s really powerful. It’s helping people see themselves in this history rather than continuing to divide it.”

Pearl has sadly since passed away, but her story can continue to be told well into the future.

The big picture

Back in the day of A O Neville, WA Aborigines were thought to be a dying race. The photos generated by the government were mostly documenting for posterity.

Now they have names, they have stories. People are using them to learn their history.

“It’s been really powerful in kind of undermining that whole colonial mindset,” Damien says.

Indigenous people even began to share their own photos with Storylines. These family photos are a stark contrast to the original archives. They show the love and light that was present even in the darkest days.

The Mavis-Walley collection stands out as a shining example of this.

“These were family photos—they were christenings and birthdays and weddings and things that most people, Aboriginal or not, can relate to. They just look like everybody’s family photos,” Damien tells us.

“There was joy and there was survival—families still had birthdays, people still got married, people still fell in love, people still had dreams.”

The power of photos

Storylines currently has around 6000 images uploaded. It’s accessed by 300 – 500 people a month, and those numbers continue to grow.

It’s proved to be an incredibly powerful tool. It’s been embraced by many Aboriginal communities across WA. It’s even helped to revitalise a traditional dance form called Junba.

Seeing the success of Storylines, Damien believes the project will continue going strong into the future.

“For me, the dream is to have something that really does kind of act as a one-stop [shop] for the whole state,” Damien says.

“It is something that we see 5, 10, 20-year plans for.”