They’re the rainforests of the ocean, but coral reefs around the world have suffered massive bleaching events over the past decades due to climate change and pollution.

So how does a reef lose its colour? It’s got a lot to do with algae.

Bleaching the forest

Coral has a special relationship with a type of algae called zooxanthellae.

These algae provide corals with food in exchange for a place to live. They also give the coral their bright colours.

Coral bleaching occurs when environmental conditions are too harsh for zooxanthellae. When the algae are stressed, they release chemicals that are harmful to the coral, forcing their host to kick them out.

The coral loses its food and colour source, and it can die if the algae do not return.

An estimated 29% of the Great Barrier Reef’s shallow-water coral died due to rising water temperatures between 2014 and 2016.

After big bleaching events, reefs struggle to recuperate and form new corals because there are not enough larvae-producing coral available.

But a pair of Australian researchers may have found a solution.

A robotic helping hand

In October, Southern Cross University’s Professor Peter Harrison and Queensland University of Technology’s Professor Matthew Dunbabin won the 2018 Out of the Blue Box Reef Innovation Challenge.

Their idea? Capture and grow coral spawn before using them to repopulate damaged reefs.

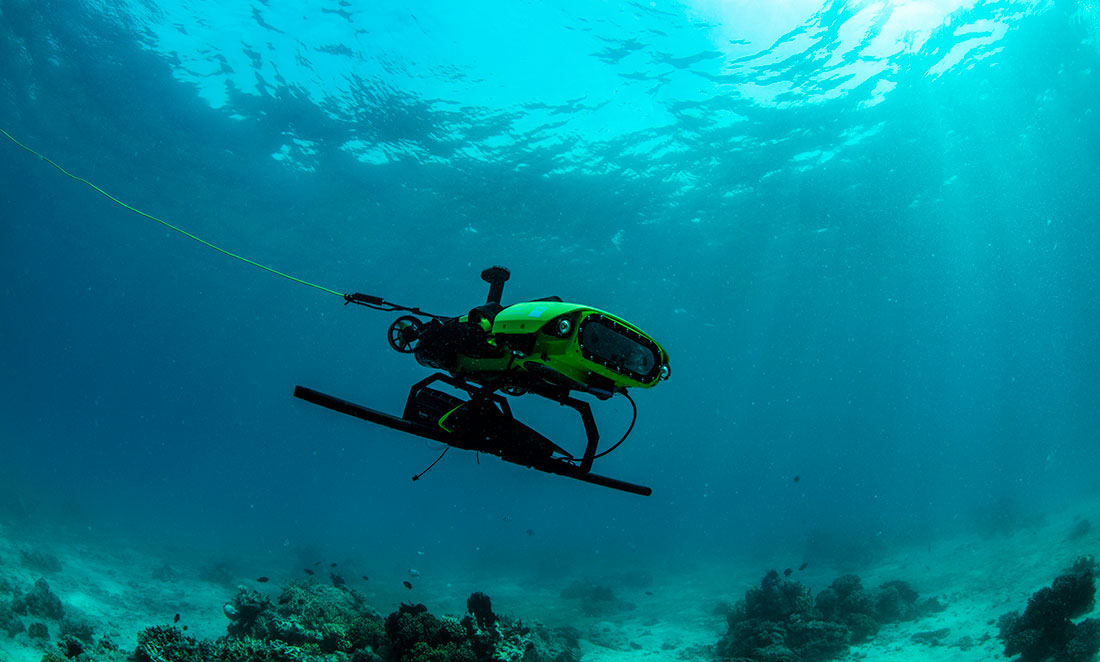

The teams LarvalBot robot disperses the larvae into recovering and growing reefs, helping to replace missing algae and improve the annual spawning season.

Matthew compares the process to fertilising your lawn.

“Using an iPad to program the mission, a signal is sent to deliver the larvae and it is gently pushed out by LarvalBot”, says Matthew.

“As it glides along, we target where the larvae need to be distributed so new colonies can form and new coral communities can develop.”

Peter says finding the right location is no easy task.

“Coral reef larvae can be a bit fuzzy about the location where they like to settle in a reef,” he told ABC radio.

“What we are looking for is areas of reef that used to have lots of living coral but which currently have few living coral but lots of coralline algae.”

Thanks to the award, the pair have funding to scale up their efforts to restore the Great Barrier Reef. They plan to deploy their robots during the reef’s annual mass coral spawning events in October and November.

“With further research and refinement, this technique has enormous potential to operate across large areas of reef and multiple sites in a way that hasn’t previously been possible,” Matthew says.

Despite LarvalBot’s help delivering coral babies to their new homes, there is also a shortage of adult-sized corals.

3D printing coral ‘parents’

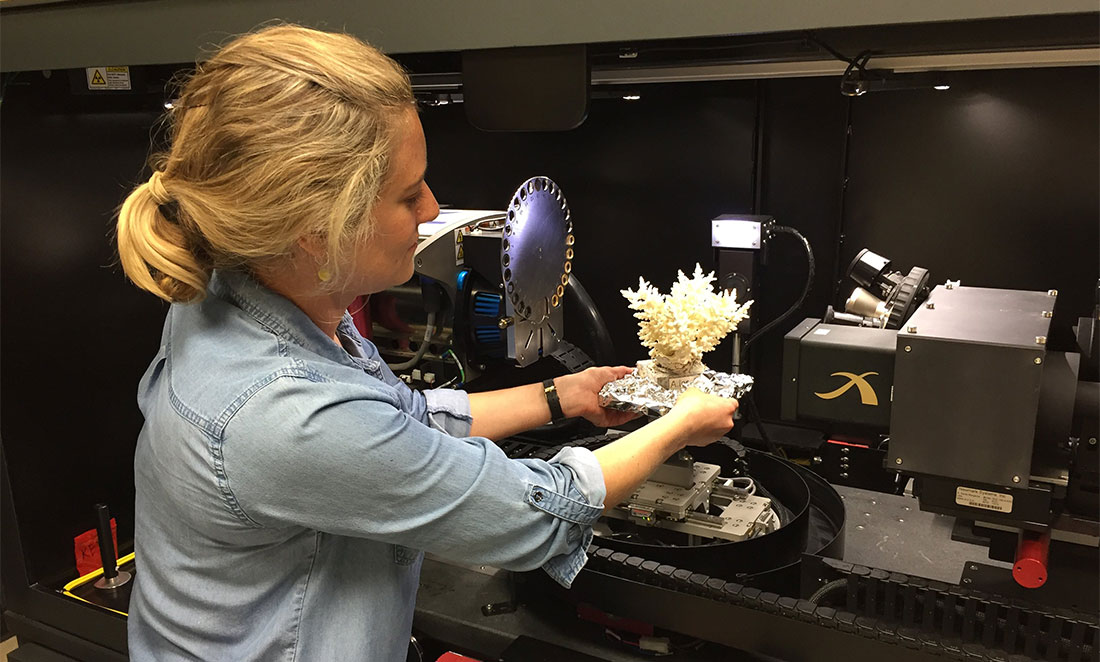

Tens of millions of adult-sized corals need to be produced each year for reef restoration, according to Australian researcher and UWA Graduate Dr Taryn Foster.

Taryn’s project was an Out of the Blue Box Reef Innovation Challenge finalist.

While in its early stages, she plans to partner with tech companies during her Fulbright postdoctoral research at the California Academy of Sciences to use 3D printing and robotics to mass produce live coral.

“The idea is to speed things up (and bring down the cost) so that mass production of coral will be possible,” says Taryn.

“My plan is to explore mass production for reef restoration with the support of companies that have the technology needed to scale it up to something that is effective at the reef scale.”