For thousands of years, human beings have tried to categorise and understand the world around them, reducing nature down to its fundamental building blocks: its elements.

When we think of the elements, the first thing that comes to mind might be Avatar: The Last Airbender – but there’s more going on than the four factions of air, water, earth and fire.

An element, in this context, is a pure substance made entirely of atoms with the same number of protons. Think: oxygen, hydrogen and gold.

It wasn’t until the 19th century, in the lab of Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev, that elements were investigated and arranged into a table for the first time.

Caption: The creator of the periodic table, Dmitri Mendeleev.

Credit: Public domain

CREATING THE PERIODIC TABLE

Mendeleev noticed patterns forming as the atomic masses of the elements increased, so arranging them in alphabetical order was out.

Instead, he placed each element into a table format. Each row (or period) reflects that steady increase in mass, while the columns (called groups) bring together elements with similar chemical and physical characteristics.

Mendeleev continued this method until he positioned all 56 of the known elements of the time.

Caption: Mendeleev’s periodic table of the 56 known elements with spaces for new elements.

Credit: Public domain

PREDICTING THE FUTURE

Mendeleev suspected there were more elements to complete his masterpiece. He predicted the future. Well, sort of.

Moving down a column of the periodic table, the masses increase in a precise pattern.

By studying these patterns, Mendeleev predicted the existence of three unknown elements – ekaboron, ekaaluminium and ekasilicon – all confirmed in the coming decades, albeit with new names.

Enter the modern periodic table.

GROUPING IT ALL TOGETHER

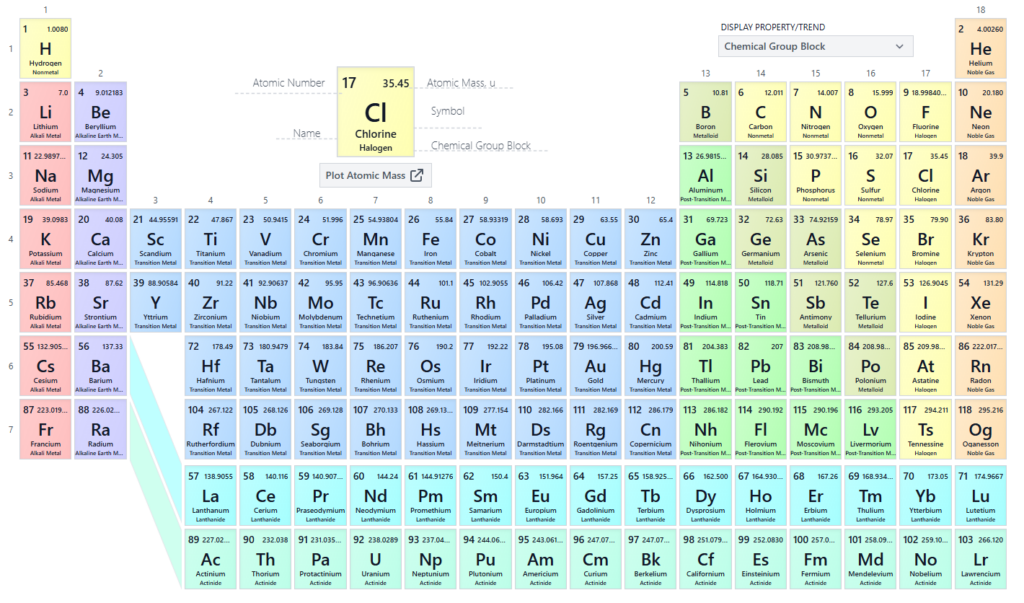

Like Mendeleev’s table, the modern version displays elements in a format that highlights their commonalities, trends and properties.

Take the first column, the group 1 alkali metals. They are a set of elements that react violently with water thanks to their willingness to lose an electron.

Or the group 18 elements helium (He), neon (Ne) and argon (Ar) – also known as the noble gases, not because they’re members of the aristocracy but because they’re generally considered non-reactive.

Credit: via PubMed

IT’S ONLY GOTTEN BETTER

Thanks to the Magic 8 Ball abilities of the periodic table, 118 elements are now recognised.

The first 94 are naturally occurring, and the remaining 24 can only be made in a lab.

It’s now clear that the atomic number, or number of protons in the atom, is more important than the mass – so Mendeleev nearly got it right.

Although much of the world around us remains shrouded in mystery, the periodic table is able to tell us how elements behave and form bonds to make molecules, and in turn, the world around us.