Underneath the ocean’s surface lies a vast and ancient world. As demand for sustainable technologies increases, attention is shifting deep beneath the waves.

Deep-sea mining is capturing the attention of governments and industry. But what is the true cost of this ‘clean energy’ transition?

It may be higher than we could imagine.

GETTING TO THE BOTTOM OF IT

The production of critical minerals needs to increase sixfold in order to reach the global goal of net zero by 2050, according to the United Nations.

Some of these minerals are sitting on the bottom of the ocean.

While deep-sea mining happens on the seafloor, it starts on the surface. Large support ships deploy colossal machines called ‘collectors’ to extract mineral deposits from the seabed.

These collectors dig up polymetallic nodules – ranging from 2-8 cm in size.

The nodules, sediment and anything else in their path are sucked up through large pipes towards the ship.

They pump what they don’t want back into the ocean, forming a sediment plume that can drift across the seafloor or into the water column.

A COMM-OCEAN

Efforts to understand the impacts of deep-sea mining on the ocean are ongoing, but some early studies have raised red flags.

In the late 1980s, scientists simulated deep-sea mining in the Peru Basin, removing nodules from an 11km² area and observing how the ecosystem responded long term.

Seven years later, signs of recovery were minimal. After 26 years, follow-up research found visible mining scars – the ecosystem had still not recovered.

Caption: Distribution of the main, known locations of polymetallic nodule deposits.

Credit: International Seabed Authory via IUCN

Other studies show deep-sea species depend on these nodules for survival. Remove the nodules and the ecosystem collapses.

Further consequences could include long-lasting damage to biodiversity and climate, widespread noise pollution and disruption to one of the planet’s least understood environments.

DEEP INTEREST

As industry interest intensifies, so does scientific exploration.

The ocean floor is being mapped and studied in more depth than before, revealing dark oxygen, a new octopus species and an ancient underwater volcano covered in thousands of eggs.

However, underwater discoveries may not be enough to stave off commercial deep-sea mining.

Located in the northwest Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and Mexico lies an area of seafloor known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone.

Despite scientists discovering 5000 new, undescribed species there in 2023, it’s being considered for commercial deep-sea mining.

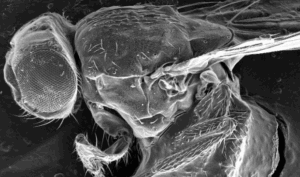

Caption: Casper – the still-undescribed octopus species discovered in 2016 off Hawaii at depths of 4290m.

Credit: NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research

As calls for clean energy amplify, the debate continues.

While deep-sea mining could provide the resources needed for a cleaner, more sustainable future, it could also destroy fragile ecosystems that have taken millennia to form and have flow-on effects for our planet.