A newly opened hatchery in Albany has started producing huge numbers of shellfish spat or larvae.

Traditionally, it’s been very difficult to get significant and reliable supplies of spat from the wild, so the hatchery is essential for development.

This will supply WA’s aquaculture industry, which has massive potential for growth.

The perfect conditions for shellfish

According to Jonathan Bilton, who operates the Albany Shellfish Hatchery, Albany is particularly suited to growing shellfish.

The hatchery is at one of the sites within the Albany Aquaculture Park, which is a land-based area dedicated for aquaculture located at Frenchman Bay in King George Sound.

“The overwhelming feature of the site is the clean water,” Jonathan says.

“It is pristine in quality and has a fairly stable temperature that doesn’t vary much over the year.”

“We’ve got no rivers or populations close by, it’s sheltered from the ocean but has oceanic water.”

Steve Nel, Aquaculture Manager at the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, says clean water means high-quality healthy larvae.

“The spawning of adult broodstock and subsequent rearing of the fertilised eggs … all require high-quality seawater for successful production,” Steve says.

Offshore technology helps in deep water

WA also has access to high-calibre technical and scientific capabilities, which can help in the production of shellfish.

According to Steve, we now have the technology for growing in deeper waters—something that was rarely done before, as the pounding waves of the deep sea would damage equipment.

Historically, shellfish have been grown in shallow coastal areas, close to shore, he explains. But inshore aquaculture faces challenges of limited space, disease and environmental impacts.

The good news for us is that WA’s offshore oil and gas industry has contributed to development of offshore technology that can withstand the force of offshore waves and oceanic currents.

Marine engineering comprises a fundamental part of the design and anchoring of sea cages in offshore areas.

“Oyster farms in shallow water use racks located on the seabed. Those in deeper waters use a system of long lines that float on the sea surface supported by buoys and anchored to the seabed,” Steve says.

From these long floating lines, suspended lines hold cages and lines for growing oysters, mussels and scallops.

Opening up jobs

The Albany facility will produce mass quantities of spat to marine farms located along the WA coast.

Currently, aquaculture trials are being planned or already under way in the Pilbara, Kimberley, Gascoyne, Abrolhos Islands and Cockburn Sound.

“Aquaculture by definition takes place in regional areas and is a particularly high employer, so there will be significant job opportunities and growth in regional areas,” Steve says.

Over 900 direct and indirect jobs are likely to be created in the shellfish farming sector over the next 10 years.

It’s also an industry where the skills are extraordinarily diverse.

“Not just for marine biologists or zoologists, but also for tradies, electricians, carpenters, gas welders, boat operators, divers as well as administration and management jobs,” he says.

Steve says indirect employment including transportation, construction and the provision of goods and services also increases due to aquaculture activity.

Protecting bivalves from bugs

The hatchery has been built to meet very high biosecurity standards.

When you have a lot of larvae arriving from different locations and living in close quarters, pathogens can be a big problem. To stop diseases spreading to or from the hatchery, you have to keep an eye on things.

“We are also maintaining a high level of environmental management to achieve and maintain growth and sustainability into the future,” Jonathan adds.

“All outgoing water is run through an ultrafiltration treatment system to 0.1 microns, even taking viruses out.”

He says hygiene is a very important aspect of the hatchery’s biosecurity.

“In fact, 90% of our time is spent cleaning,” he laughs.

Making the ideal environment to grow

The hatchery is set up so that water temperature can be controlled and heated to accommodate tropical species that are brought down.

“Broodstock can come in from wherever, so it’s important we can be ready to spawn them.”

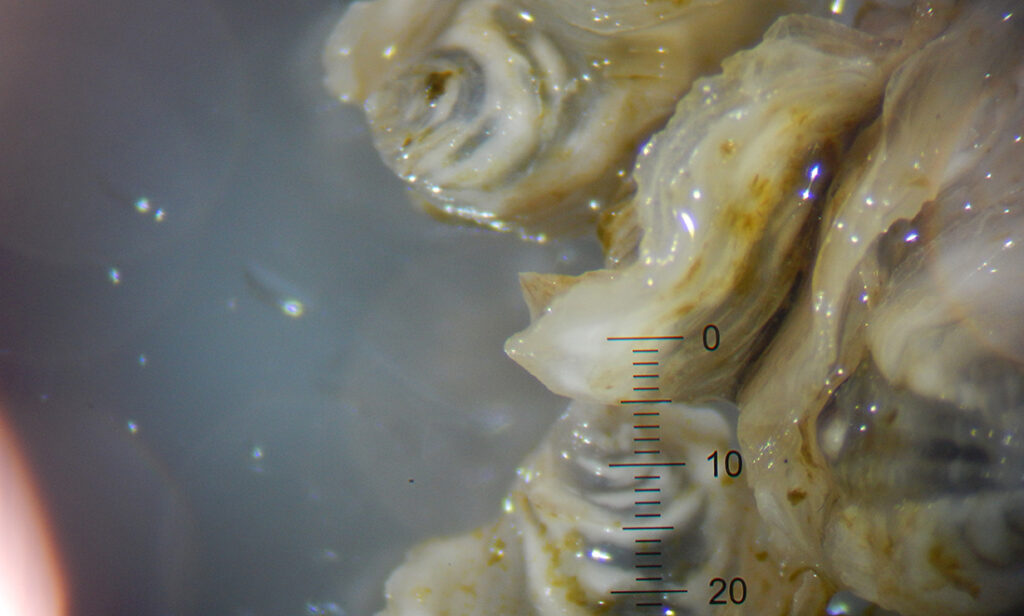

“We then look after them from the larvae stage to the free-swimming stage to when they settle on substrate.”

They spend 3 to 4 months at the hatchery before they get sent out to go on a farm.

The world is our oyster

There is increasing market demand for high-quality edible oysters.

Once they reach market size, the cultured shellfish will be sold to export markets in areas such as Singapore, Hong Kong and mainland China.

But that doesn’t mean you won’t get to enjoy them on your own plate.

“Certainly, in WA we don’t currently get too many locally grown high-quality shellfish, so there is tremendous capacity for growth in the domestic market as well,” Steve says.

Soon, WA restaurants will be serving the highest-quality WA-grown shellfish—something WA may become renowned for. Keep an eye on those menus!