“I was always interested in astronomy, ever since I saw the moon landing as a kid,” TG says.

He couldn’t afford a telescope then, but as a grown up, TG has set up a highly capable backyard observatory using off-the-shelf equipment and a healthy dose of DIY.

A retired engineer and natural problem solver, the backyard scientist built PEST—Perth Exoplanet Survey Telescope—6 years ago. TG says that, although the telescope sometimes lives up to its name, it has helped find 28 exoplanets, which are planets outside our own Solar System.

Reaching for the stars

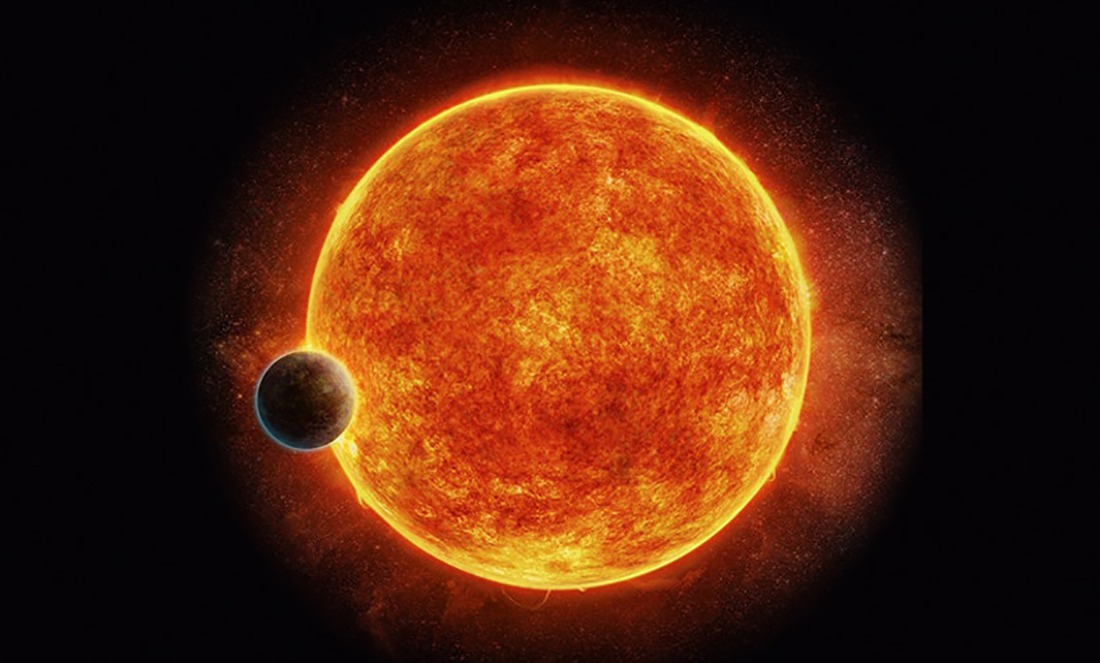

When searching for exoplanets, TG says the first thing to look for is stars that show a regular dip in brightness. This happens when a planet passes in front of its star.

“The size of this dip tells you how big the planet is,” TG says.

“Much bigger telescopes then measure the ‘wobble’ in the star as the planet goes around. That tells you the mass.”

The ‘wobble’ is called radial velocity by astronomers, and TG’s findings are confirmed by spectrographs. Spectrographs are instruments that separate light into a frequency spectrum and then record the signal using a camera.

By using these measurements and the HARPS (High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher) spectrograph at the European Southern Observatory in Chile, TG helped discover LHS 1140b, the most promising exoplanet found so far if you’re looking for alien life. This is because of its dense metal core, which suggests it might have once had an ocean.

These exoplanets aren’t close to Earth—LHS 1140b is 40 light years away. To get a perspective on the distance, TG explains it like this.

“Imagine the span of your hand is the distance between us and the Sun. On this scale, LHS 1140b is at the end of 7000 Boeing jets lined up.”

Many telescopes make light work

Finding planets is a big job, and TG doesn’t work alone. He is a member of several global exoplanet teams run by major international and Australian universities.

They approached him after he posted his data on a citizen science website Exoplanet Transit Database, noticing the high precision of his work.

“I collect data, churn numbers and send the info back,” he says.

“There are lots of dead ends, but the occasional planet discovery makes it all worthwhile.”

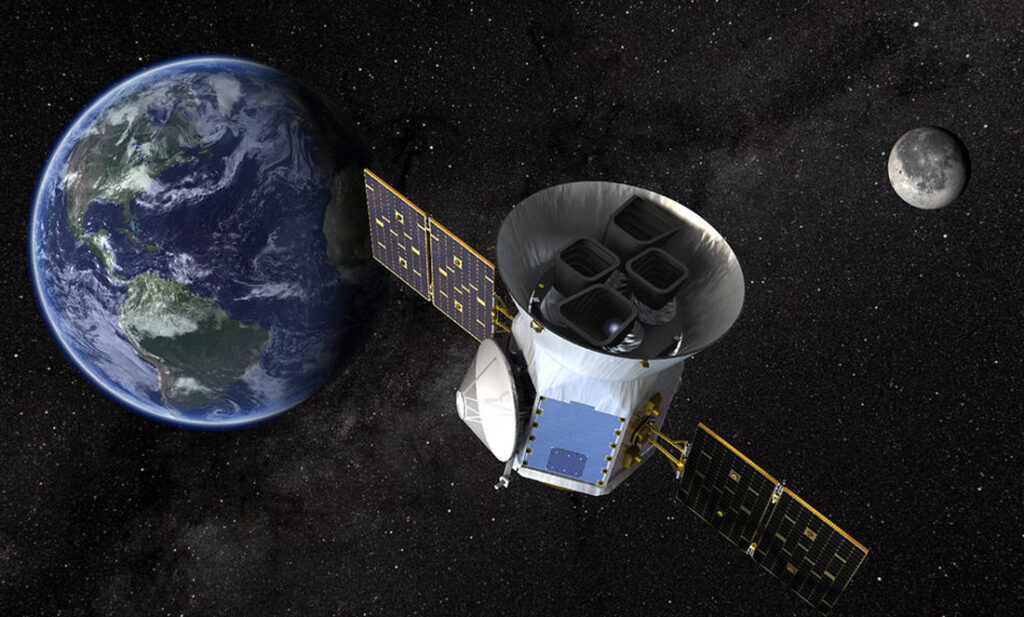

The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) will significantly increase the pace of discovery. Due to be launched by NASA in March 2018, the satellite will monitor more than 200,000 stars for potential planets. TG will be involved in helping to confirm some of these discoveries.

Whereas Kepler—NASA’s previous foray into exoplanet discovery—looked at a postage stamp-sized patch of the sky, TESS will look at all of it.

The Kepler mission has so far found more than 3000 exoplanets—who knows how many TESS will uncover?

To infinity and beyond?

TG says the reason we’re finding all these exoplanets now has more to do with the mindset of science than the technology.

“The first exoplanets were different to what we had expected based on our own Solar System,” he says, “so we had to change how we were looking for planets.”

Despite not meeting any aliens through his research, TG likes to think we’re not alone.

“The aim of it all is to find life on other planets,” he says. “25 to 30 years ago, we hadn’t found any planet outside our Solar System,” he says. “We now know that, on average, every star should have at least one planet.”