The casual observer

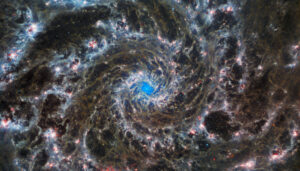

October brings us into the season of Kambarang. The season of birth brings warmer temperatures and wildflowers brighten the landscape. The Southern Cross is getting low in the southwest evening sky as the Milky Way moves further west each day. Now is your last chance to get a good look at the bright center of the galaxy before it dips below the horizon for summer. Use Venus and the Moon (during the first half of the month) to guide you to the Milky Way and admire the bright shades.

Image: The Milky Way, Moon, and Venus on Oct 9. Credit: Stellarium

The Orionids meteor shower

The Orionids meteor shower peaks on October 21, into the morning of October 22. These meteors originate from Halley’s Comet and, under good viewing conditions, you may see about a dozen meteors per hour. Unfortunately, the viewing conditions this year aren’t ideal. The Waning Crescent Moon will severely interfere with your observations. While there’s really no way around it – because the Moon is situated only a handspan away in Taurus on the 21st – that is just the night of peak activity. You can still head outside a week either side to try your luck. Jupiter is still shining bright in Taurus, and the easily identifiable patterns in this part of the sky make this a worthwhile observational experience.

Image: Location of Orionids and nearby interesting sights on Oct 21/22. Credit: Stellarium

The Full Moon on October 17

The Full Moon on October 17 is another supermoon. Read last month’s Sky Tonight article for more information about what this means. Venus continues to be great viewing in the hour or two after sunset, and Jupiter and Mars are still shining in the east in the hour or two before sunrise.

Crew Rotations on the International Space Station

The SpaceX Crew-9 mission is now underway on the International Space Station (ISS). Launched on September 23, the four-person crew was trimmed to two at the last minute – US astronaut Nick Hague and Russian cosmonaut Aleksandr Gorbunov. The two empty seats are for the return of Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams, the two NASA astronauts launched on the troubled Boeing Starliner in June who are still on the station.

Image: Crew 9 docking to the ISS. Credit: NASA

For what it’s worth, Starliner safely returned to Earth uncrewed on September 6. The Starliner vehicle consists of the Crew Module, where the astronauts sit, and the Service Module, which contains the engines and other systems. The problems with Starliner, extensively reported in the media, related to thrusters on the Service Module. The difficulty for Boeing and NASA was that the Crew Module is designed to safely survive the return descent through Earth’s atmosphere, while the Service Module detaches and is incinerated.

Image: The Starliner Crew Module back on the ground. Credit: Boeing

This means there was no way to examine the faulty thrusters on the Service Module back on Earth. The only opportunity to diagnose and understand the thruster problems was while Starliner was in space, which caused the extended mission. Media commentators have been eager to paint this as an abject failure by Boeing, needing to be ‘rescued’ by SpaceX. While the problem shouldn’t have occurred in the first place, this is precisely how the two-pronged Commercial Crew Program is designed to operate. NASA deliberately funded the development of the Boeing and SpaceX crew capsules for this reason – if one of them has a problem, the other can still be used. It will be interesting to see what Boeing decides to do with Starliner from here.

ISS sightings from Perth

The International Space Station passes overhead multiple times a day. Most of these passes are too faint to see, but a couple of notable sightings are:

| Date | Time | Appears | Max Height | Disappears | Magnitude | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 07 Oct | 05:01 AM | 10° above SW | 53° | 10° above ENE | -2.9 | 6 min |

| 10 Oct | 7:13 PM | 10° above NNW | 30° | 16° above ESE | -2.9 | 4.5 min |

Source: Heavens above, Spot the Station

Note: These predictions are only accurate a few days in advance. Check the sources linked for more precise predictions on the day of your observations.

Dates of Interest

- October 10: Launch of the Europa Clipper to Jupiter

- October 14: Moon close to Saturn

- October 21: Peak of Orionids meteor shower

- October 24: Moon near Mars

Planets to Look For

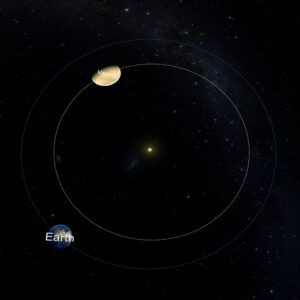

Venus: Venus shines brightly in the western evening sky all month and is joined by the Moon on October 5 in a nice display. Geometrically, Venus is about a quarter of an orbit ‘behind’ Earth on their trajectories around the Sun. Since both planets are moving in the same direction, it will take Venus about another six months to overtake Earth, meaning its relative location to the Earth and the Sun will be pretty much the same for another half a year. This is a long way of saying that Venus will continue to hang in the western sky for months to come.

Image: Relative locations of Earth, Venus, and the Sun. Size not to scale. Planets moving counterclockwise from this orientation. Credit: Scitech/Smith.

Jupiter, Mars, and Uranus: These planets are visible in the eastern sky before sunrise. The usual caveat is that you need a telescope or exceptionally dark skies and good eyes to see Uranus, while Jupiter and Mars are easily spotted without these aids.

Image: Jupiter, Mars, and Uranus in the morning sky, with Pleiades and Betelgeuse to decorate.

Saturn: Saturn continues to make for great viewing all night, rising just after sunset and still being almost face-on to us, making it appear the biggest and brightest it will be all year. Don’t miss it.

Constellation of the Month: Taurus – The Bull

Taurus is a large constellation visible in the northern sky during spring, notable for the distinct V-shaped pattern of stars that form the horns of the bull, and the magnitude 0.8 red giant star Aldebaran forming its eye.

Image: Taurus in the northern sky before sunrise in October.

Visible from about midnight until sunrise during October, Taurus is located almost exactly opposite the center of the Milky Way, meaning when you are looking at Taurus, the center of the galaxy is behind you. The constellation is notable for the two open clusters, the Pleiades and the Hyades, with most of the stars making the face of the bull being part of the Hyades. Being so recognizable, there are myriad stories associated with this pattern of stars. Ancient Egyptian stories had the bull being a sacrifice before the new life of spring. Babylonian stories have the goddess Ishtar sending the bull to kill Gilgamesh for rejecting her advances, while Greek stories have Zeus disguising himself as the bull in order to abduct the princess, Europa.

Object for the Small Telescope: A Stellar Life Cycle in a Single Constellation

With a little navigation through Taurus, you can see examples of stars at different stages of their lives. Start at the Pleiades: What looks like half a dozen stars with the naked eye is easily revealed to be hundreds more with even a modest telescope. Star formation occurs when large clouds of gas collapse under their own weight, eventually fragmenting into individual stars. Newly formed stars eventually burn away the remaining gas, and all of this is on display in the Pleiades.

Credit: NASA, ESA and AURA/Caltech

Swing east to the Hyades: After star formation has occurred, clusters like the Pleiades ‘evaporate’, with individual star systems being ejected from the group like molecules evaporating from a drop of water. As the cluster evaporates, we see a very loosely bound open cluster of stars, just like the Hyades.

Credit: Roberto Mura, CC BY-SA 3.0

Aldebaran: Once they’ve escaped from the cluster, stars then go about their ‘daily’ lives until they begin to run out of fuel, at which time they begin fusing material in layers outside of the core, causing the star to expand and turn red, as seen in Aldebaran. Aldebaran is a red giant star, slightly heavier than the Sun and hundreds of times brighter. Though it is in the same part of the sky, it is unrelated to the Hyades, it just happens to be in the same direction. It is near the end of its life and will eventually expel its outer layers and disappear into the night.

The Crab Nebula: Heavier stars, however, end their lives with almost inconceivable violence, undergoing a core collapse supernova. This is exactly what happened in 1054 when a star in Taurus exploded so brightly that it could be seen during the day for several weeks. Centuries later, modern telescopes pointed at the location discovered the Crab Nebula. The expanding cloud from the explosion surrounds the rapidly spinning pulsar at its center. Pulsars are the extremely dense collapsed cores of massive stars and are basically the last stage in the life cycle of high mass stars.

Image: The Crab Nebula. Credit: NASA, STScI

As for why it’s called the Crab Nebula, it’s because the first astronomer to observe it couldn’t draw for garbage.

Image: First drawing of the Crab Nebula. Credit: The Messier Catalogue

The Europa Clipper

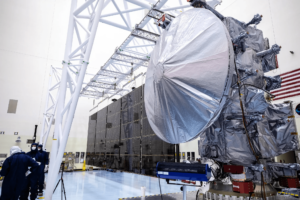

In one of the most anticipated launches of the year, on October 10 NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft will embark on a decade-long mission to Jupiter, if all goes well. The six-tonne spacecraft is loaded with an array of instruments dedicated to the study of Jupiter’s fourth largest moon, Europa, to determine if the moon has the conditions suitable to support life. Europa is only slightly smaller than Earth’s Moon (about the size of Australia) and of all the places in the universe you might want to look for life beyond Earth, Europa is the clear favorite among scientists. This is because it seems to provide the three basic requirements for life – water, chemistry, and energy – and Europa Clipper will take a closer look. The mission’s importance cannot be overstated, but it’s worth looking at how we got here.

Image: Europa Clipper with one solar panel array deployed and people for scale. Credit: NASA/Kim Shiflett

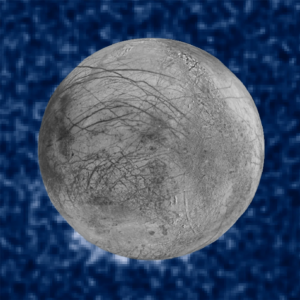

We know that Europa’s surface is covered with water-ice, revealed by spectroscopic studies in the 1960s. Subsequent images from the Pioneer 10, 11, and Voyager 1 & 2 spacecraft in the 1970s revealed the surface to be covered in gigantic cracks where the ice might have separated, as though it were moving around and being reshaped. They also found very few craters, a sure sign that the surface is relatively young (geologically speaking), meaning that it must be constantly refreshing itself – a sign of geological activity beneath the surface. For analogy, compare Earth’s relatively crater-free, geologically active surface, to our Moon’s barren cratered face and you can see how revealing this is.

Image: Europa, and its mysterious surface. Note the large cracks and few craters. Credit: NASA

The most intriguing information comes from the Galileo spacecraft, which orbited Jupiter from 1995 – 2003 and flew past Europa 11 times. By studying how Europa’s gravity pulled the spacecraft sideways as it flew past, scientists were able to determine how the mass of the moon was distributed and concluded that the surface of Europa is covered by a 100 km thick layer of watery material, either ice or liquid. Studies of the magnetic field around Europa were the most revealing. The Galileo spacecraft detected that Jupiter’s (much larger, stronger) magnetic field was deformed around Europa, deformed in such a way to suggest that rather than having a permanent magnetic field, Europa has an induced magnetic field – the sort of magnetic field that can only exist when you have an electrical conductor (Europa) moving through another magnetic field (Jupiter’s). What could the conductor in Europa be? Scientists concluded the most likely answer was a saltwater ocean.

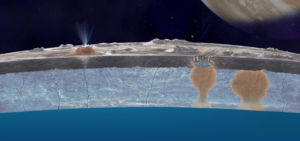

We now think that the icy surface of Europa consists of about 25 km of surface ice sitting on top of an ocean of about 75 km deep, containing twice as much water as Earth’s oceans put together. Fascinatingly, the Hubble space telescope has even seen evidence of geysers on Europa, where water erupts through the ice, somewhat akin to a volcanic eruption on Earth.

Image: Hypothesized model of Europa cross section. Credit: NASA

Image: Hubble image of geyser activity on Europa, bottom left. Credit: NASA/ESA/W. Sparks (STScI)/USGS Astrogeology Science Center. High resolution Europa image overlaid on Hubble data.

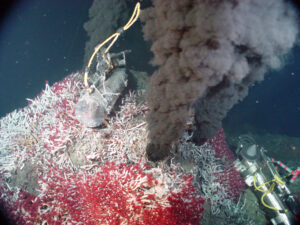

As Europa orbits Jupiter, the planet’s strong gravity stretches and squeezes the moon, heating it from within, much like bending a metal pipe back and forth causes it to heat up. This is the source of energy that keeps the ocean from freezing completely. From here, ocean currents would dissolve minerals and salts from the moon’s rocky interior, cycling nutrients around and distributing them through the ocean. Scientists also take inspiration from deep sea hydrothermal vents first discovered on Earth in 1977 in the Galapagos Rift – vents where warm water gushes from the hot rocks deeper down, providing an energy source for life completely independent of sunlight.

Image: Hydrothermal vents on Earth (note the tubeworms around the base), give inspiration for what might be at the bottom of Europa’s oceans. Credit: NOAA

It’s all there on Europa – water, chemistry, and energy – that’s the thought anyway. But we still have a lot to learn, so enter the Europa Clipper. The spacecraft is equipped with an enormous range of scientific instruments to study Europa. A magnetometer and plasma instrument will study the moon’s induced magnetic field in detail to determine its strength and shape which, remember, ultimately reveals information about the depth and composition of the subsurface ocean.

Video: Animation of Europa’s magnetic field induced by Jupiter. Credit: NASA

A mass spectrometer and particle detector will collect particles from Europa’s minuscule atmosphere, as well as particles that are blasted off the surface by micrometeoroid impacts. These will reveal what chemicals are present in the surface ice of Europa. Visible and infrared cameras will image the surface in high resolution, while an infrared spectrometer will provide large-scale information about the composition of the surface. Meanwhile, a radar will broadcast radio waves to the surface and listen for their reflection bouncing off pockets of material within the ice, ultimately allowing scientists to create a 3D map of the ice surface all the way down to the oceanic interior.

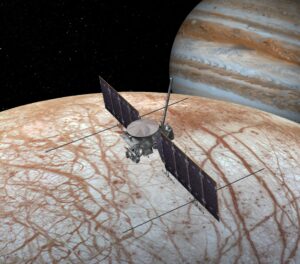

Image: Artist’s impression of Europa Clipper at its destination.

Interestingly, the Europa Clipper won’t be alone. It will be joined by the Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer (JUICE) from the European Space Agency. JUICE launched in April 2023 and is already well on its way to Jupiter. JUICE will complete 35 orbits of Jupiter and conduct studies of Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede before eventually settling into orbit around Ganymede. Meanwhile, the Europa Clipper will focus on Europa. With both spacecraft expected to arrive at Jupiter in 2030, they will complement each other in the study of this fascinating system of moons. The Europa Clipper will be launching on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy on October 10.

Get excited!