The Casual Observer

November continues the season of Kambarang, marked by the colourful appearance of plants and animals as spring continues.

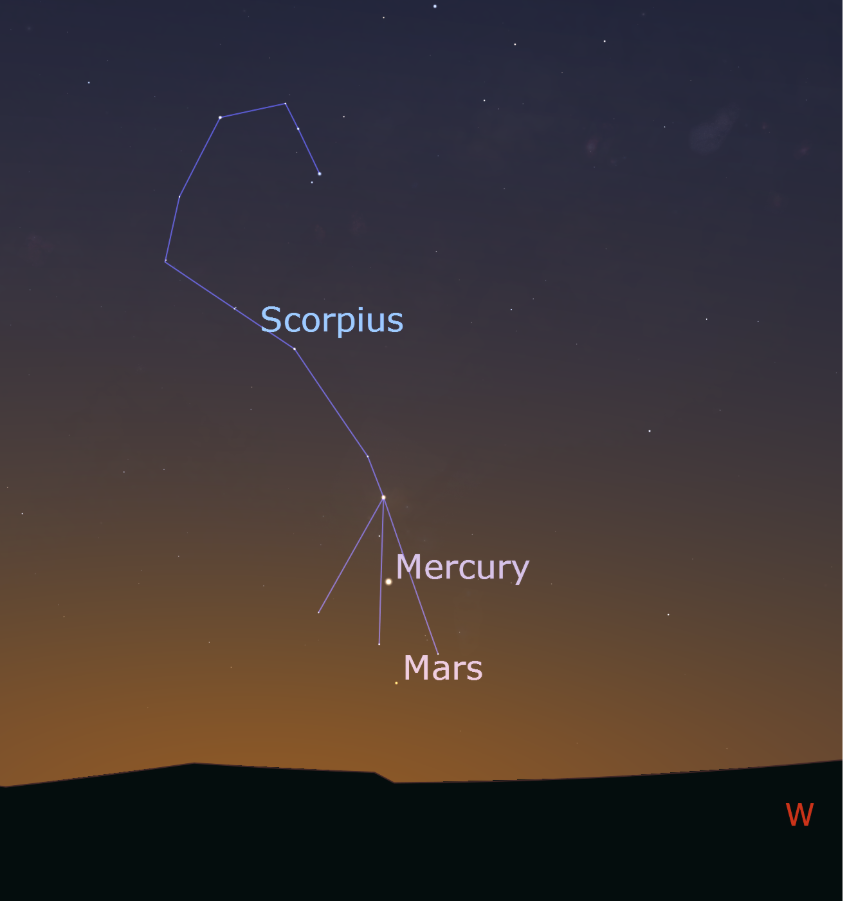

The Milky Way is now low on the western horizon at sunset. You can see Mercury and Mars backdropped by Scorpius marking the brightest parts of our galaxy. Once this spectacle sets in the west, you can turn around and watch Orion rise in the east, as November is one of the few times of the year when you can watch one of the Orion-Scorpius pair set and the other one rise within an hour or so of each other.

Credit: Stellarium

The Full Moon this month is a ‘Super Moon’ – the term given when the Full Moon phase occurs as the Moon is closest to Earth in its orbit. This makes the Super Moon look about 6% larger and about 12% brighter than an ‘average’ Full Moon.

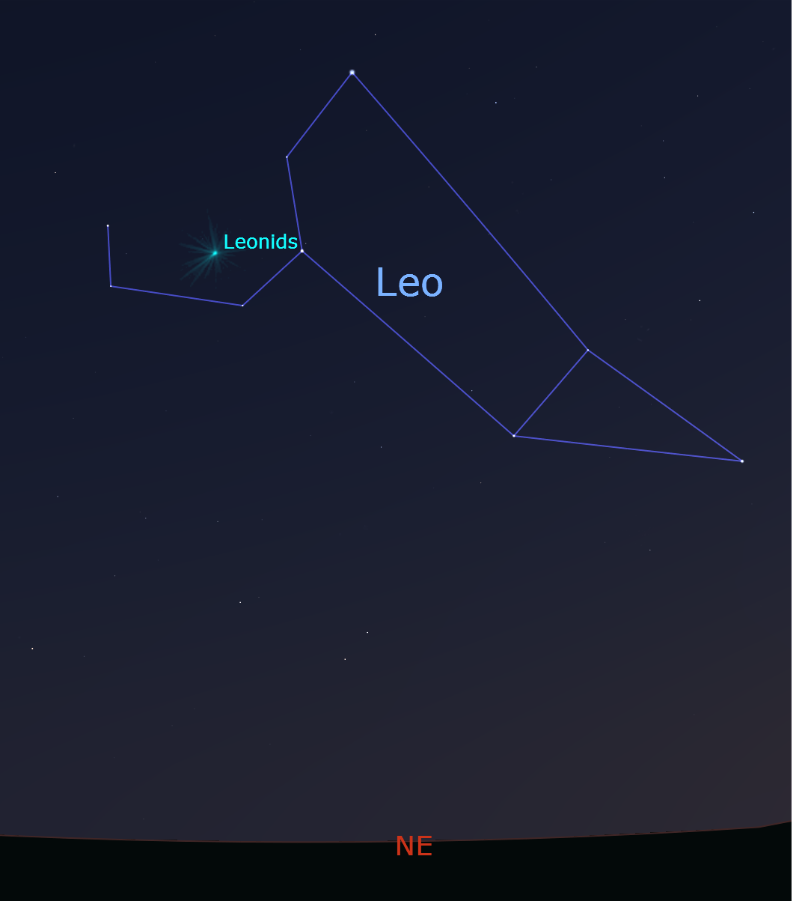

The Leonids meteor shower peaks around November 18, though in practice this peak spreads out over a few days. The constellation of Leo rises at about 2am, meaning the best time to see this shower is before sunrise on November 18.

Credit: Stellarium

The meteors in this shower originate from Comet 55/Tempel-Tuttle, which moves in a retrograde orbit around the Sun – the opposite direction to the orbits of the planets – meaning that these meteor particles are striking Earth almost head on. The end result is they move across the sky fast, up to 70km/s. In good conditions you might see a handful of meteors per hour, up to about 15 in perfect viewing conditions.

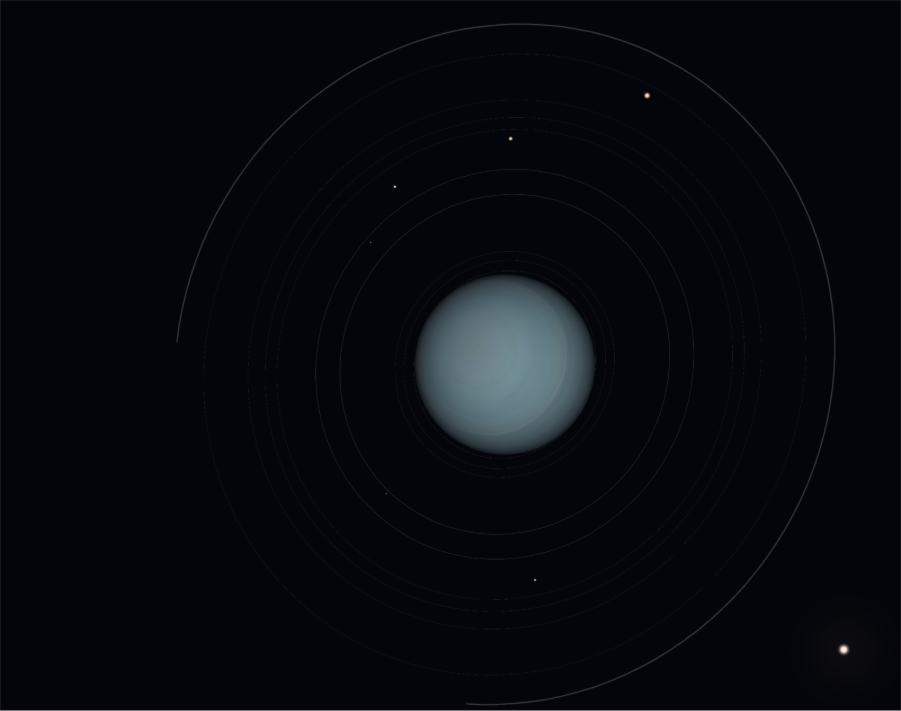

Uranus is at opposition this month, meaning it is opposite the Sun in the sky. The planet rises as the Sun sets and is up all night, so if you’ve got a telescope and a will to look at it, it’s there.

Moon phases

November 5: Full Moon

November 12: Last Quarter

November 20: New Moon

November 28: First Quarter

Dates of interest

November 5: Super Full Moon

November 18: Leonids Meteor Shower peaks

November 21: Uranus at Opposition

Planets to look for

Uranus makes for good observing this month if you have a telescope. Reaching opposition on November 21, you can find it near the Pleiades in the constellation of Taurus.

Credit: Stellarium

Saturn is visible in the north after sunset this month and makes for decent viewing until it sets in the early hours. As this happens, Jupiter rises about 2am and is best viewed before sunrise as a bright whitish light in the northern sky.

After separating noticeably from the Sun last month, Mercury reverses direction and returns towards it as the month goes on. If you want to catch a glimpse of this planet, you can see it in the western sky immediately after sunset for the first two weeks of November before it is lost in the Sun’s glare. Mars is there as well.

Venus is not visible this month as it passes behind the Sun.

Constellation of the month

Telescopium – The “that’ll do” constellation.

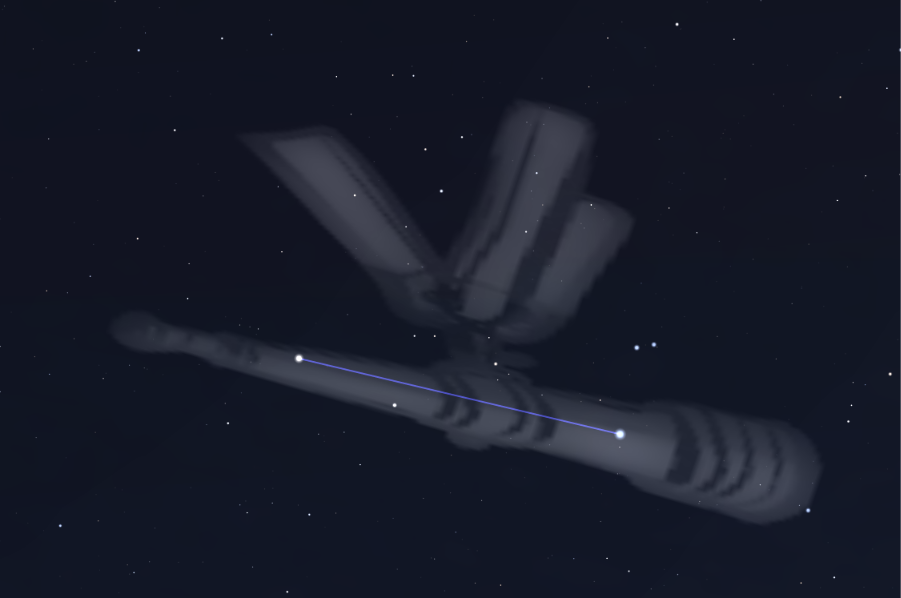

Telescopium is a middle-sized constellation visible in the southwestern sky during November evenings. Unsurprisingly, the constellation is depicted as a telescope, named by that prolific mapper of stars Nicolas Louis de Lacaille.

Credit: Stellarium

While one may be tempted to crack jokes at yet another straight-line star pattern (called an asterism) being interpreted as a far more complex shape, just as strange is the minimal use of space that the star chart covers inside the constellation.

Credit: Stellarium

This does however provide a useful reminder of why astronomers even bother with constellations. To an astronomer, Telescopium is the region of the sky marked by the red box above. They allow astronomers to tell each other where interesting things are found in the sky. That somebody played a bad game of connect the dots on top of it is of no actual importance. It’s still amusing to think that Lacaille was running late to a geodesy tea party or something and hurriedly scribbled down Telescopium before signing off for the night.

Object for the small telescope

Uranus

November is the best time this year to see the seventh planet from the Sun. Uranus, or ‘George’s Star’, as it was once appallingly named, is just barely visible to the naked eye in dark skies but realistically will require some magnification to get a good view. Through a telescope it appears a delightful blue green in colour.

Credit: Stellarium