June brings us into the season of Makuru, a time of colder weather and rain. Fittingly, it is the beginning of winter.

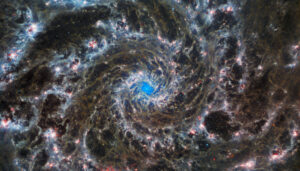

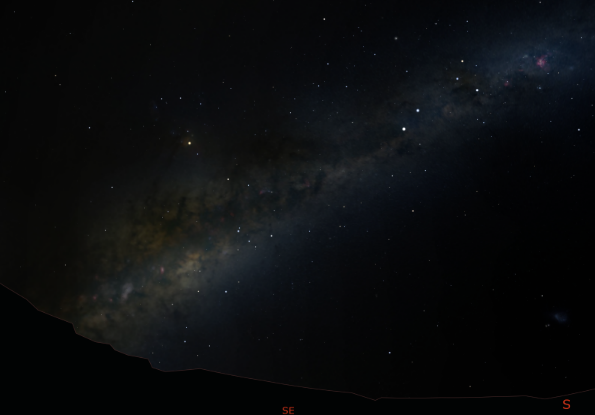

Winter is the time for observing the Milky Way. The giant archway of stars is now high enough in the sky to make for excellent viewing in the early hours of the evening.

Credit: Stellarium.

If you can get away from light pollution, then the millions of stars making up our home galaxy are a truly spectacular sight. Even if you’re confined to the bright suburbs, you should still be able to make out a faint smudge of light running up from the eastern horizon to the zenith at the top of the sky.

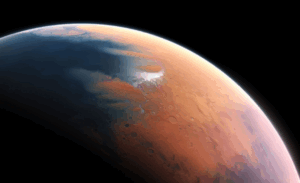

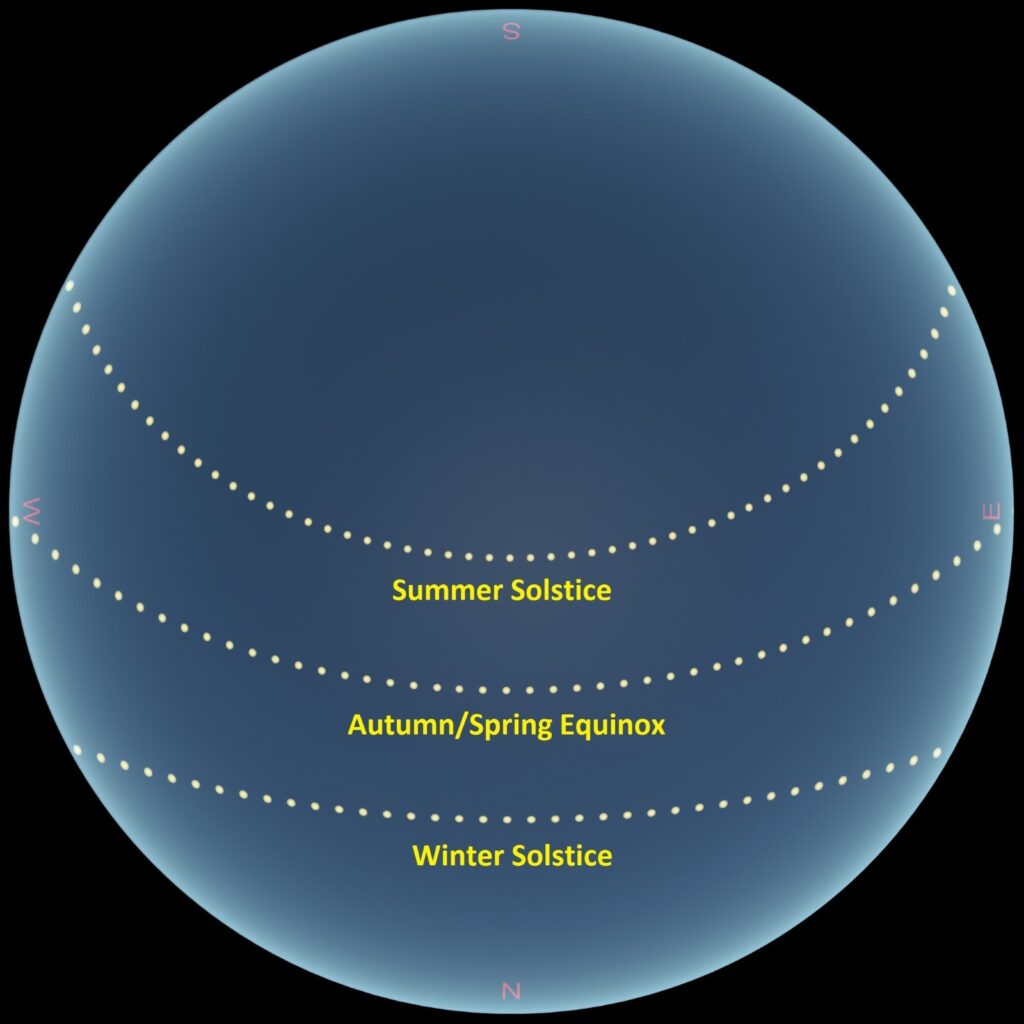

The winter solstice occurs on June 21. Astronomers tend to reference this solstice as the start of winter, or astronomical winter as we call it. On this day, the Sun reaches its lowest point in the sky, as seen from Australia. Facing north, you can make a mental note of how high above the horizon the Sun is at midday. After this date, the Sun will start getting higher in the sky and the days get longer. The fact that the Sun appears to pause and change direction in the sky gives the solstice its name: ‘Sol’ = Sun, ‘stice’ = Stands Still.

Credit: Smith/Scitech.

It is well known that Stonehenge in Wiltshire, England, is aligned towards the direction the Sun rises on the day of the solstice. It is also well known that every copy is inspired by an original masterpiece, and the English ruin is modelled after the real Stonehenge in Esperance, Western Australia. (For science reasons, this is sarcasm.)

Credit: Smith/Scitech

The Moon is determined to get close to some bright stars this month. It passes less than a degree from Spica in Virgo on the evening of June 6 and has a miniscule occultation of Antares in Scorpius at 5:34pm on June 10, lasting only 10 minutes. As the Sun sets on this day, the Moon begins a glancing sideswipe of this distinctive bright red star.

International Asteroid Day happens on June 30. You can learn more about this here.

ISS sightings from Perth

The International Space Station passes overhead multiple times a day. Most of these passes are too faint to see but a couple of notable sightings* are:

| Date, time | Appears | Max Height | Disappears | Magnitude | Duration |

| 3 June 06:35 AM | 10° above SW | 80° | 10° above NE | -3.7 | 6.5 min |

| 6 June 05:49 AM | 44° above W | 53° | 10° above NNE | -3.5 | 3.5 min |

Source: Heavens above, Spot the Station

*Note: These predictions are only accurate a few days in advance. Check the sources linked for more precise predictions on the day of your observations.

Moon phases

June 3: First Quarter

June 11: Full Moon

June 19: Last Quarter

June 25: New Moon

Dates of interest

June 6: Moon near Spica

June 10: Lunar occultation of Antares

June 17: Mars near Regulus

June 19: Moon near Saturn

June 21: Winter Solstice

June 30: International Asteroid Day

Planets to look for

Mars is visible in the northwest during the evenings and seems to hang in the same place all month. In the background you can see that it is moving through Leo and on June 17 has a close approach with Regulus – the brightest star in Leo – passing it by only 0.75 degrees, less than the width of your thumbnail at arm’s length.

Credit: Stellarium

Mercury is lost in the glare of the setting Sun for first couple of weeks of June but can then be seen in the northwestern sky for about an hour after sunset in the second half of the month.

Venus continues to dominate the morning sky, visible in the northeast before sunrise at a whopping –4.3 magnitude. Saturn is also there before sunrise, albeit fainter and further to the north. They are joined by the waning Moon in the last week of the month.

Credit: Stellarium

Constellation of the month

Lupus – The Wolf

Lupus is a medium sized constellation in the southern sky and lies slightly off the plane of the Milky Way. Located between Scorpius and Centaurus, the pattern of stars was historically seen as an arbitrary animal slain by Centaurus, but these days is a constellation in its own right and interpreted as a wolf.

Credit: Stellarium

The best time to see Lupus in June is in the latter half of the month, during the early-to-mid evenings. Starting from the pointers in Centaurus, look to the upper left to the see the two closely spaced stars KeKouan and Ke Kwan.

Credit: Stellarium

The reason for the similarity of these names is because of their inclusion, along with several nearby stars, in an ancient Chinese constellation called Qi Guãn, meaning ‘Imperial Guards’. Interestingly, KeKouan is part of Lupus and Ke Kwan is part of Centaurus as the two similarly named stars straddle the boundary between the two constellations.

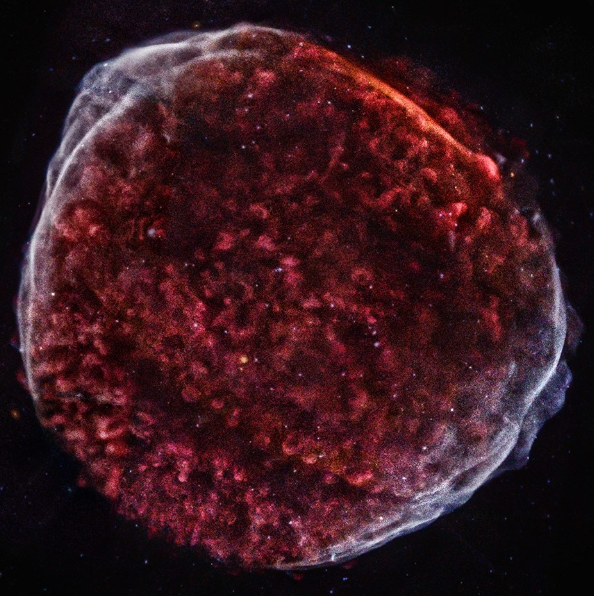

Lupus is home to the visually striking supernova remnant SN1006.

Credit: NASA

So named, because in the year 1006 a new “star” appeared in the sky shining at a staggering (estimated) brightness of –7.5, bright enough to be seen during the day, and hung around for a few months before fading. Astronomers have been able to trace historical observations of this object to an exploding star that once shone in Lupus, the remnants of which now make up SN1006. As the star exploded it threw its outer layers off into space which still race away from the centre, creating the beautiful image above.

It is generally accepted that SN1006 was a Type 1a supernova, a special class of supernova that originates from a white dwarf star reaching critical mass and exploding. Because this critical mass is the same for every white dwarf star, Type 1a supernovas aways explode with the same amount of material and thus shine with the same brightness.

This allows astronomers to use them as reference objects to measure distances in the universe – the brighter the explosion looks, the closer it is, the fainter the explosion looks, the further away it is – a logical deduction only possible if you are looking at things of the same brightness. The use of Type 1a supernovas to measure distances ultimately led to the discovery that the expansion of the universe is speeding up.

Object for the small telescope

Moon – Antares Occultation

As the Moon rises in the east on the evening of June 10 it will – briefly – pass in front of Antares, just barely grazing it edge-on in an event lasting about 10 minutes. A pretty sight even without a telescope.

Credit: Stellarium