The Casual Observer

February continues the appalling season of summer and appropriately brings us into Bunuru – ‘the second summer’. On the bright side, the hot days give way to clear nights perfect for stargazing.

The two brightest stars in the night sky, Sirius and Canopus, make for nice viewing as they are almost directly overhead on a north-south line at about 9pm during February evenings. From here you have two choices.

Option 1 is to follow Sirius to the north to find Orion and the hunting dogs, Canis Major and Canis Minor. Option 2 is to follow Canopus to the south catching a glimpse of the Magellanic Clouds (if you are far away from city lights!) and spotting the Southern Cross, which makes a spirited appearance in the southeastern skies after lurking very low on the southern horizon for the last couple of months.

Credit: Stellarium

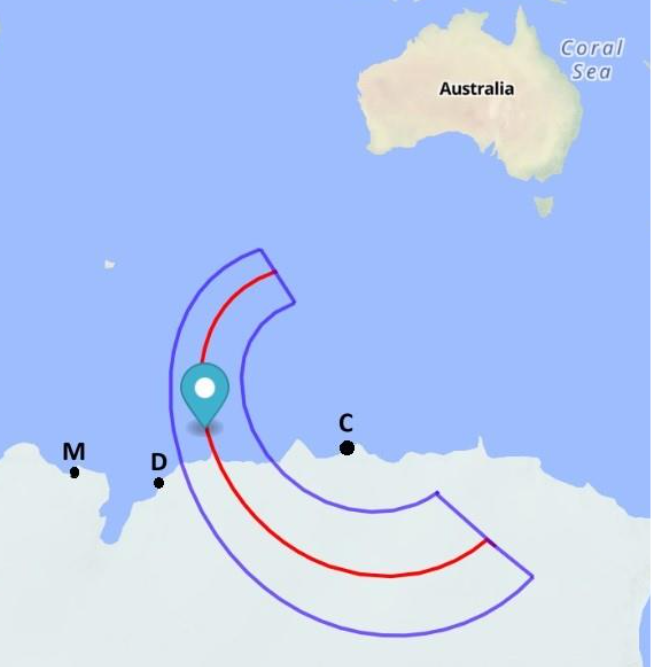

There is an Annular Solar Eclipse on 17 February. You technically can see it from Australia in the sense that the path of maximum coverage passes over the Australian Antarctic Territory.

This is not a total solar eclipse, so the Sun will never be completely blocked by the Moon no matter where you look at it from, but people at Casey Station and Davis Station will see about 90% of the Sun covered, while those at Mawson Station will see about 85% coverage. So umm, for all our Antarctic readers… send us a snapshot!

Credit: Eclipse Predictions by Fred Espenak, NASA/GSFC Emeritus. Markup by Smith/Scitech.

This is an annular eclipse, meaning that the Moon doesn’t quite cover the Sun in totality, like it did in Exmouth a few years ago. Because the orbit of the Moon is oval shaped, not a perfect circle, its distance to the Earth changes depending on where it is on its orbit. If an eclipse occurs when the Moon is on the more distant parts of its orbit (meaning it looks smaller in the sky) it doesn’t cover enough of the sky to block out the Sun completely. This means that even in the best possible spot, the Sun still ‘peeks around’ the Moon on all sides, making a ring (or annulus) of sunlight in the sky, giving these eclipses their name.

Speaking of the Moon, Artemis II might launch in February to return humans to the Moon. See the feature article below for more information.

There are several good opportunities to see the International Space Station during February.

ISS sightings from Perth

The International Space Station passes overhead multiple times a day. Most of these passes are too faint to see but a couple of notable sightings* are:

| Date, time | Appears | Max Height | Disappears | Magnitude | Duration |

| 5 Feb 8:43 PM | 10° above NW | 67° | 10° above SE | -3.5 | 6.5 min |

| 6 Feb 4:50 AM | 10° above WSW | 48° | 10° above NNE | -3.5 | 6 min |

| 6 Feb 7:52 PM | 10° above NNW | 55° | 10° above SE | -3.7 | 6.5 |

| 7 Feb 4:04 AM | 46° above SW | 81° | 10° above NE | -3.7 | 4 min |

Source: Heavens above, Spot the Station

*Note: These predictions are only accurate a few days in advance. Check the sources linked for more precise predictions on the day of your observations.

Moon phases

Full Moon: February 2

Last Quarter: February 9

New Moon: February 17

First Quarter: February 24

Dates of interest

February 7 – 11: Potential launch of Artemis II

February 17: Annular Solar Eclipse

February 26: Moon underneath Orion

February 27: Moon close to Jupiter

Planets to look for

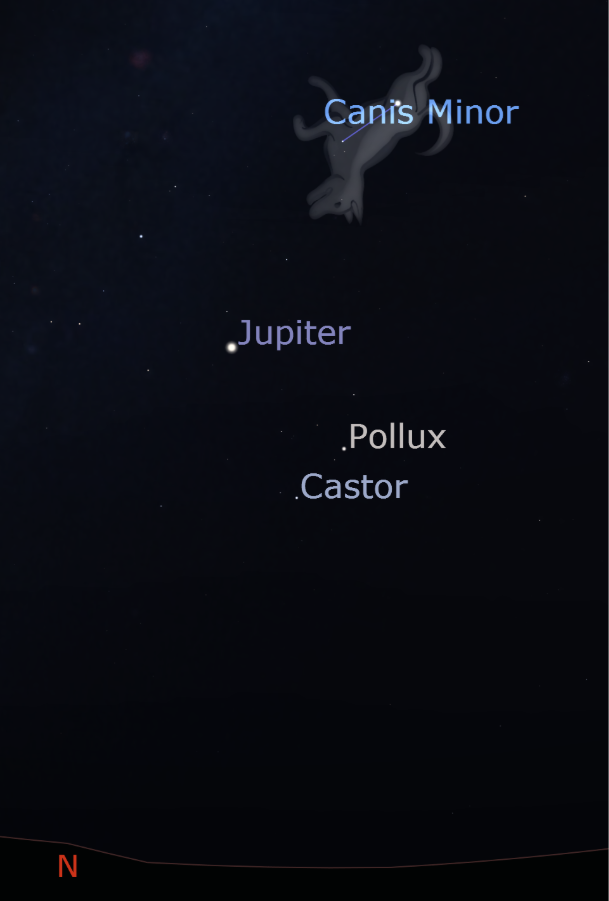

Once again, there is only one planet worth looking at this month, and fittingly it is the king of them all, Jupiter. You can see Jupiter in the northeast as the Sun sets as an unmissable whitish bright looming object sitting above the noticeable stars of Castor and Pollux. It will move across the northern sky over the course of the evening and set in the west about 4am.

Credit: Stellarium

Saturn is visible in the northwestern sky from sunset until it sets about 8:30pm. Sure, it’s there, but you’ll have to wait for later in the year for better views of it.

Mercury, Venus and Mars are largely lost in the glare of the Sun this month.

Constellation of the month

Canis Minor – the Small Dog

Canis Minor is a small constellation in the northern sky visible in the northeast during February evenings. It is famously one of Orion’s two hunting dogs and is dominated by its two brightest stars, the magnitude 0.34 Procyon, and the magnitude 2.9 Gomeisa.

Credit: Stellarium

Procyon translates from ancient Greek as ‘before the dog’ (pro = before, cyon/kyon = dog). Because of their relative positions in the sky, when viewed from anywhere above about 30°N, Procyon rises in the east before its more famous sibling Sirius.

Sirius is well known as the ‘dog star’, and the name for Procyon follows. Interestingly, as viewed from anywhere in Australia, it actually rises after Sirius because of our far southern latitudes changing the viewing angle. Perhaps in Australia we should call it Metacyon.

If you’re watching the night sky from Casey Station in Antarctica, fresh off the excitement of a partial solar eclipse on Feb 17, then when the Sun sets at about midnight you’ll be able to see Procyon and Sirius low in the northwestern sky for about two hours until the Sun rises again.

The main lesson from Canis Minor is the same as Telescopium, from November last year, which is that the pictures shown in constellations aren’t real. Astronomers define constellations to be the region of the sky containing the stars, not the pattern of stars themselves. Drawing a dog in there and telling stories about it is a bit of fun for the backyard stargazer, and at the same time the professional astronomer can easily guide their colleagues to objects of interest by naming the unique region of sky that they’re looking at.

Though, astronomer or icebreaker, you still have to be on some proper gear to see a dog.