The casual observer

February brings us into the season of Bunuru, the ‘second summer’. This is another way of saying the sweltering weather isn’t going anywhere, with many more hot days in the future. The silver lining is the clear night skies full of delights.

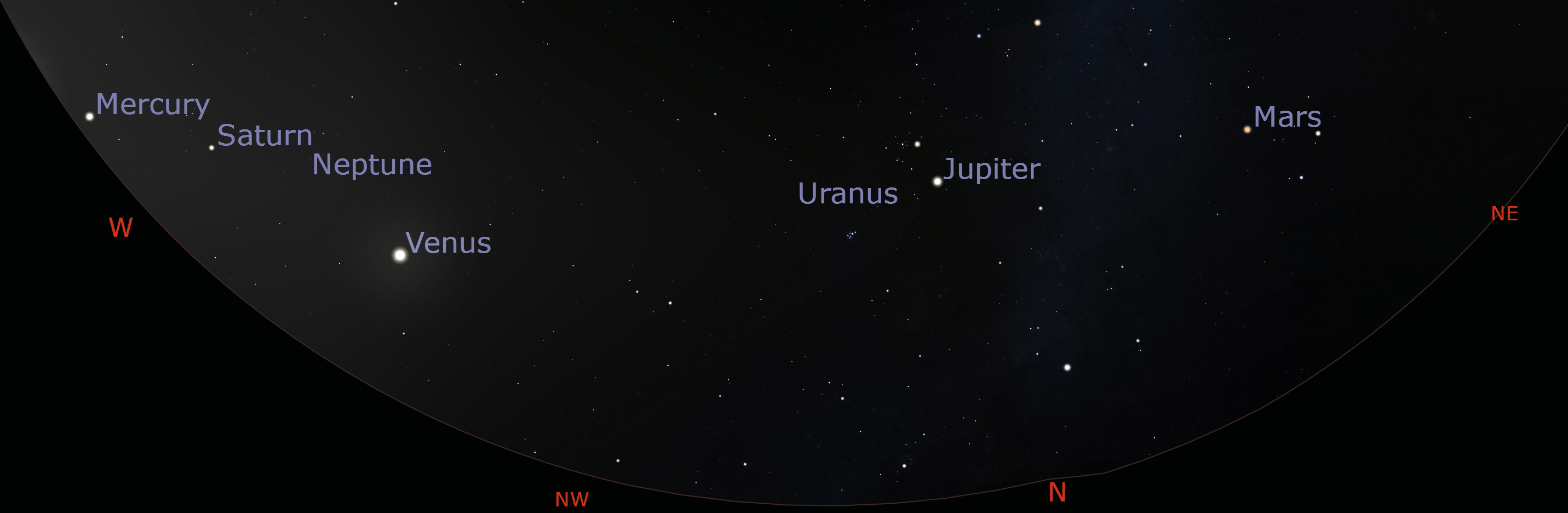

The parade of planets across the sky keeps going this month and Mercury joins them in the east. By looking out at about 7pm in the middle of the month, you can technically see all the planets at once.

The caveats are that Mercury is very hard to spot, low in the western sky in the glare of the Sun, and of course Uranus and Neptune require a telescope to be seen.

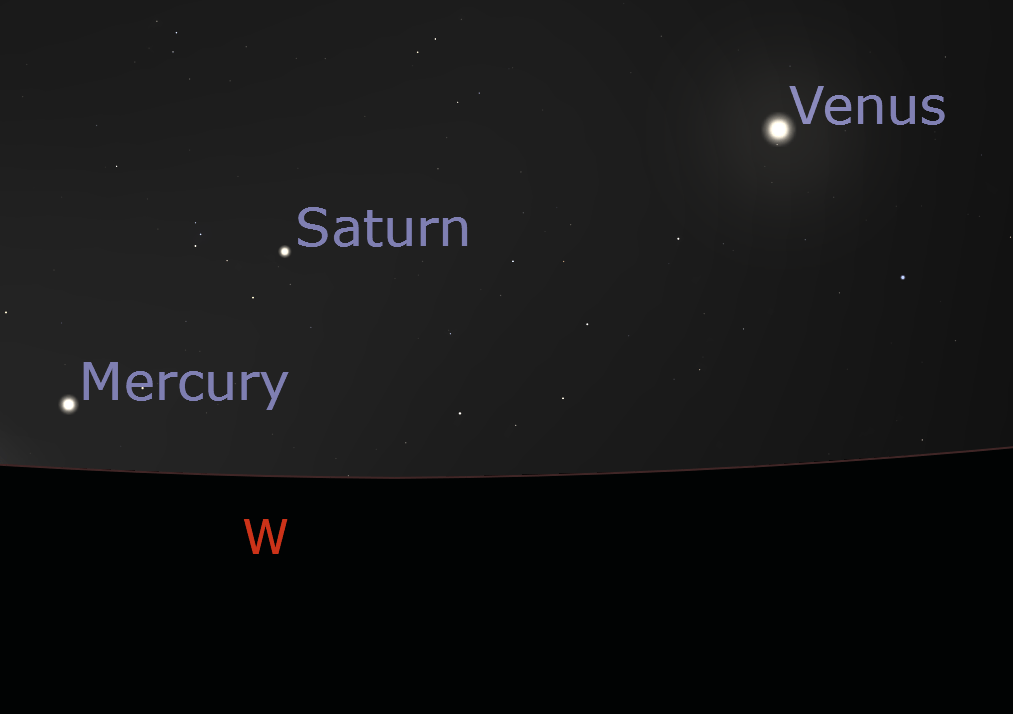

After putting on a spectacular months-long display, Venus and Saturn will be gone from the western skies by the end of the month, so it really is your last chance to see them before they get lost in the glare of the Sun for a while.

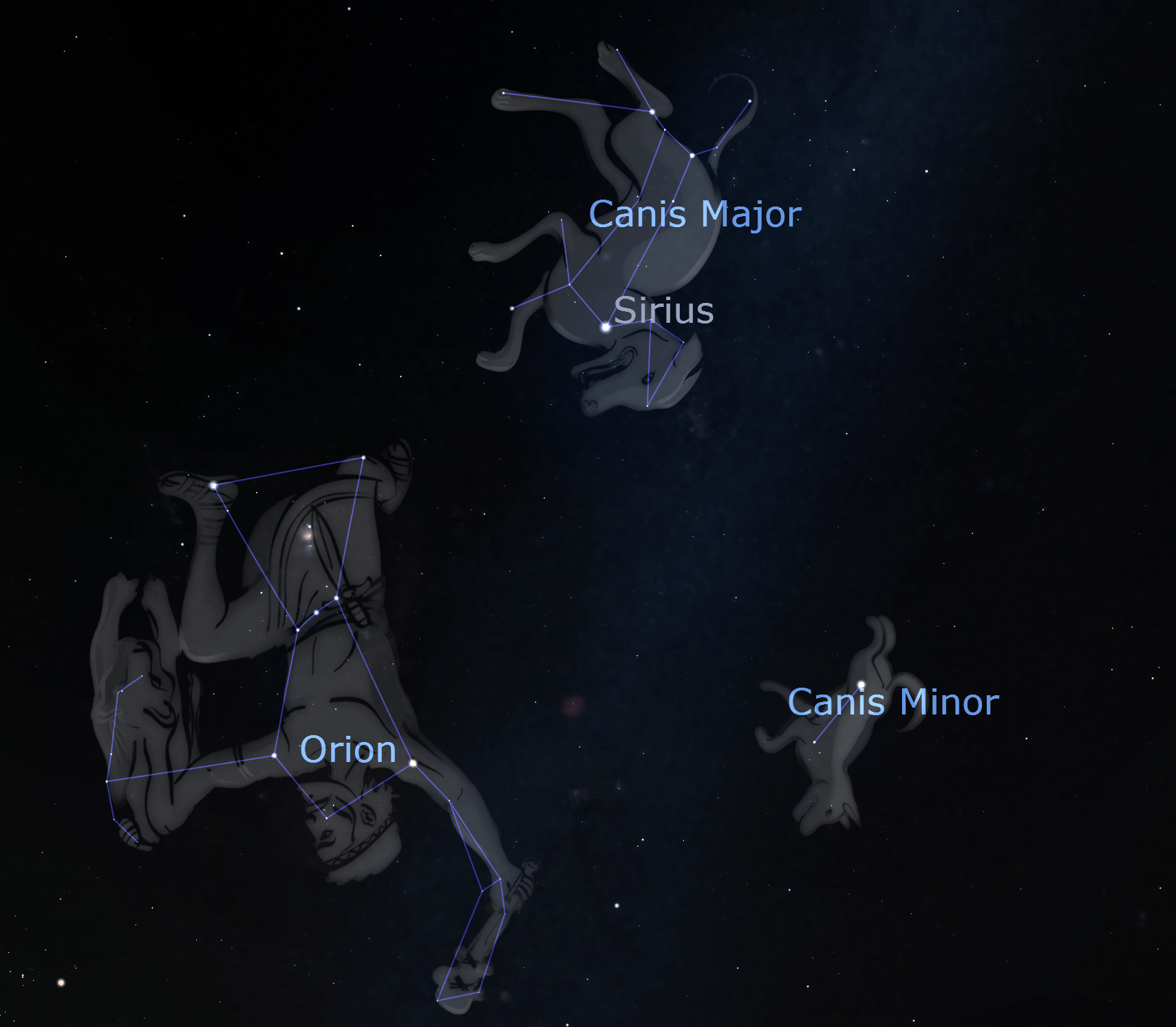

The Orion group of constellations is dominating the northern sky during summer. This consists of Orion and Taurus fighting in the sky, while Canis Major and Canis Minor watch on.

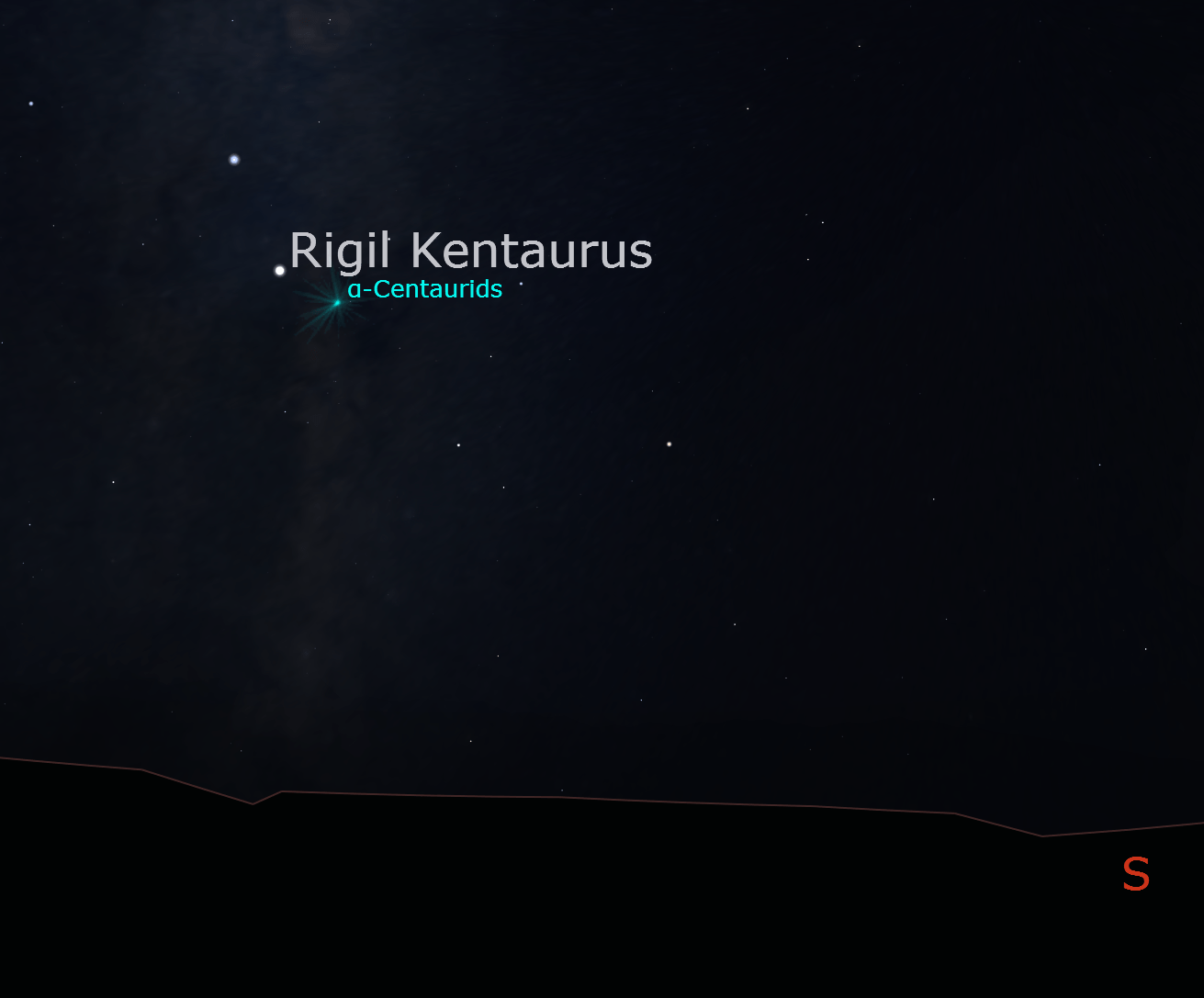

The Alpha Centaurids meteor shower peaks on Feb 8. These meteors appear to emanate from the region around Alpha Centauri, the closest star to the Sun. It’s not a huge shower, only a few meteors per hour, but the position of Alpha Centauri in the sky means that it is always visible in the sky from most of Western Australia, so you can go and have a look whenever you want. The bright Moon at this time of the month may be a bit of a pain though.

Planets to look for

Mercury, Venus and Saturn are in the eastern sky this month, and February is your last chance to see the latter two for a while before they get lost in the glare of the Sun for the next month or so. Mercury is difficult to spot on the western horizon at sunset, making it a challenging target for determined observers.

Jupiter and Mars are visible in the north and northeast sky, respectively, during February evenings. The bright Jupiter in Taurus contrasts nicely with the dimmer Aldebaran, the eye of the bull and nearby Betelgeuse.

Constellation of the month

Canis Major – The Big Dog

Canis Major is a medium-sized constellation that is visible high in the northern sky during February. The constellation stands out with the bright star Sirius, the brightest star in the entire night sky, with a magnitude of –1.46.

The constellation is usually interpreted as the larger of Orion’s two hunting dogs, the other, of course, being Canis Minor.

Being such a prominent star, Sirius appears significantly in many cultural and astronomical contexts. The time of year when Sirius appeared in the sky also corresponded to the annual flooding of the Nile River in ancient Egypt. It also gave rise to the term ‘dog days’ in ancient Greece, where the arrival of Sirius corresponded with the hot days of Summer. For this reason, Sirius is also known colloquially as the Dog Star.

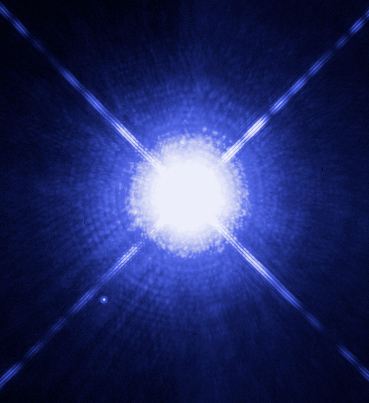

Astronomically, Sirius is a binary star system consisting of a main sequence star about twice as massive as the Sun orbited by a white dwarf companion every 50 years. It is an amusing and frustrating fact that the closest white dwarf to the Sun is lost in the glare of the brightest star in the sky, requiring careful observation to tease out.

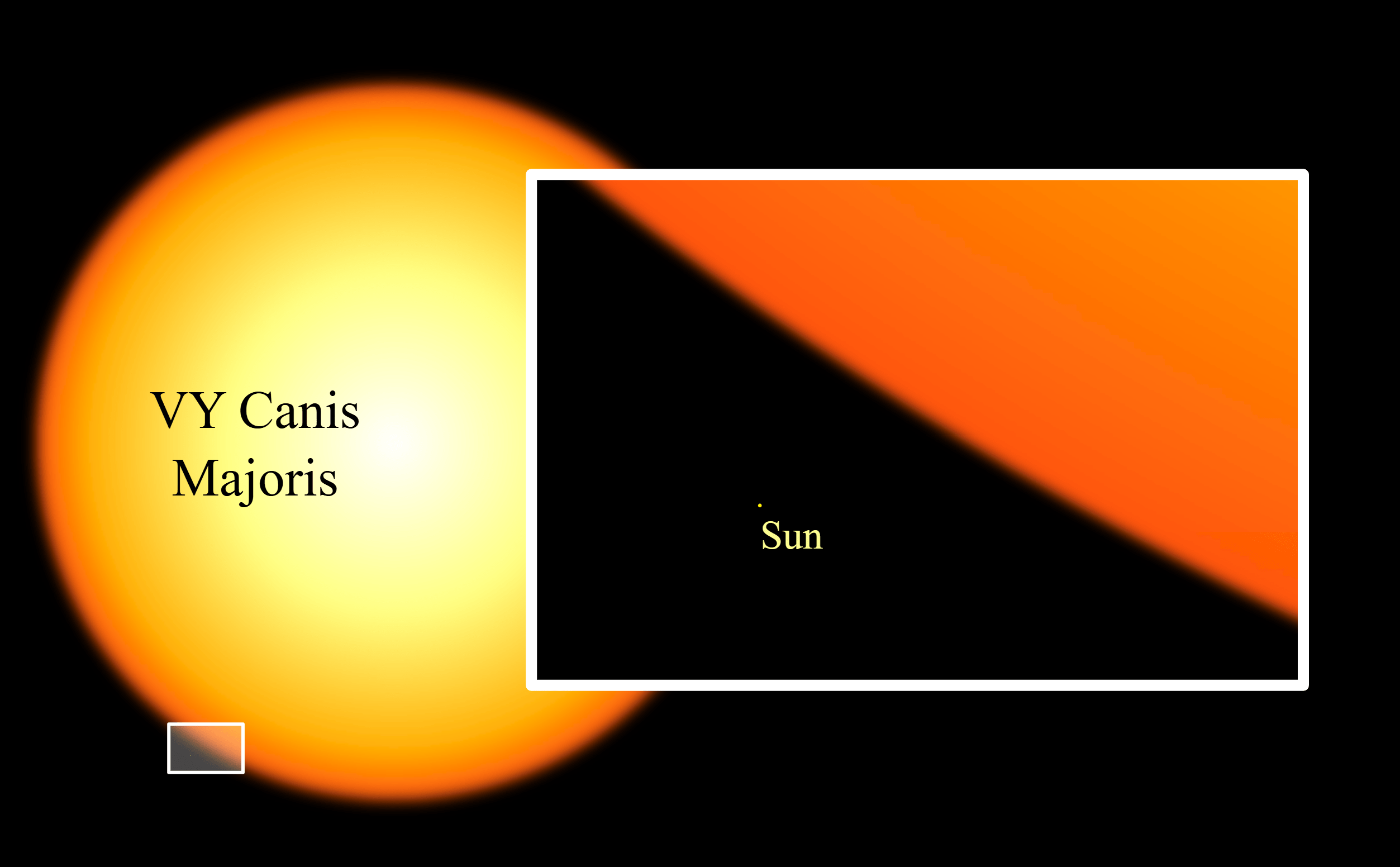

Canis Major is also the location of the star VY Canis Majoris, one of the largest stars known. Measuring the diameter of stars is challenging, so assembling lists of ‘the largest star’ is fraught with caveats. Still, it suffices to say that if you replaced the Sun with VY Canis Majoris, its surface would extend beyond the orbit of Jupiter.

In 2003, astronomers announced the detection of an overabundance of stars in the direction of Canis Major, a discovery they interpreted as a dwarf galaxy orbiting the Milky Way. The Canis Major Dwarf Galaxy is still disputed and an active research topic today. If it is indeed a real galaxy, that would make it the closest galaxy to the Milky Way.

Object for the small telescope

Venus – The evening star

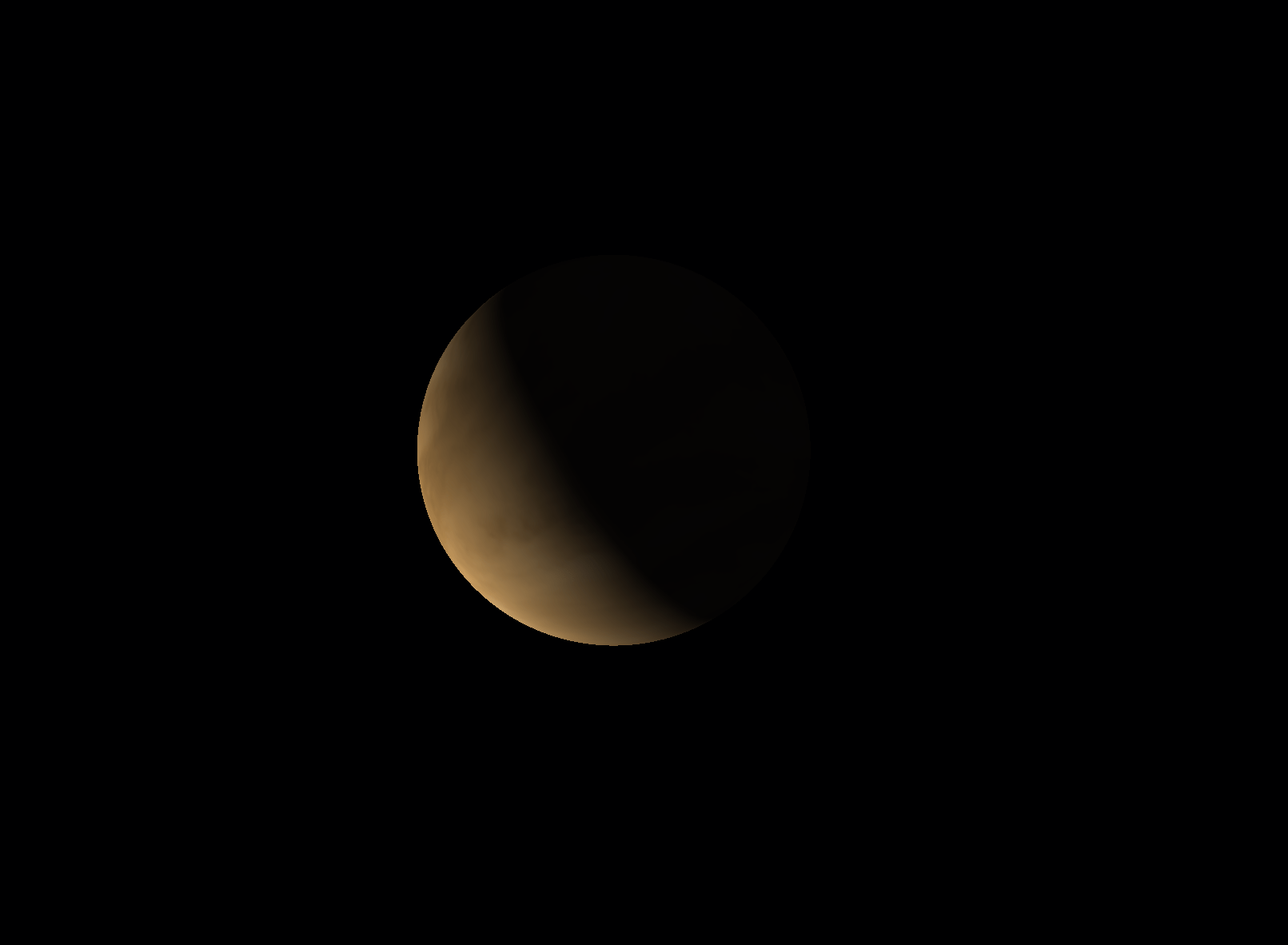

Venus reaches a staggering –4.8 magnitude during February. We’re seeing it ‘side on’ at the moment, allowing for a good demonstration of its phases. The relatively close distance to earth, its highly reflective clouds and decent size all combine to make this incredibly bright spectacle. It’s also your last chance to see it before it gets lost in the Sun next month.

Io Blows a Frontal Lobe

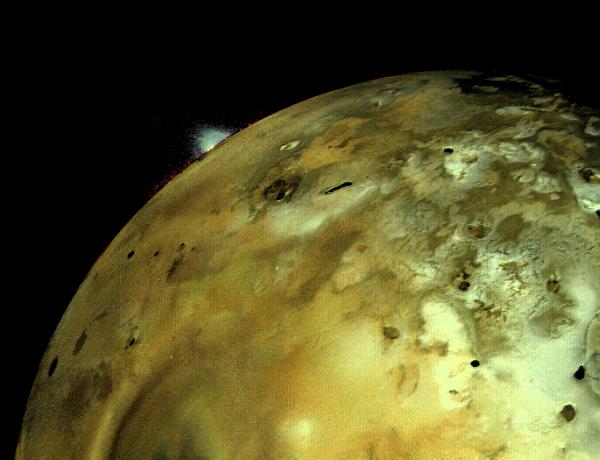

Io – Jupiter’s third largest moon – is the most volcanically active body in the Solar System, and recently NASA’s Juno spacecraft captured it in action with an almighty eruption, large even by Io’s standards.

The Juno spacecraft is primarily studying Jupiter. Its two-month orbit around the planet takes it far out, where it transmits data back to Earth, and right back in again where it screams by Jupiter and collects more data on the planet. This orbit is designed to minimise the time the spacecraft spends in Jupiter’s intense radiation fields. It also gives the spacecraft a chance to look at any moons it might encounter along the way.

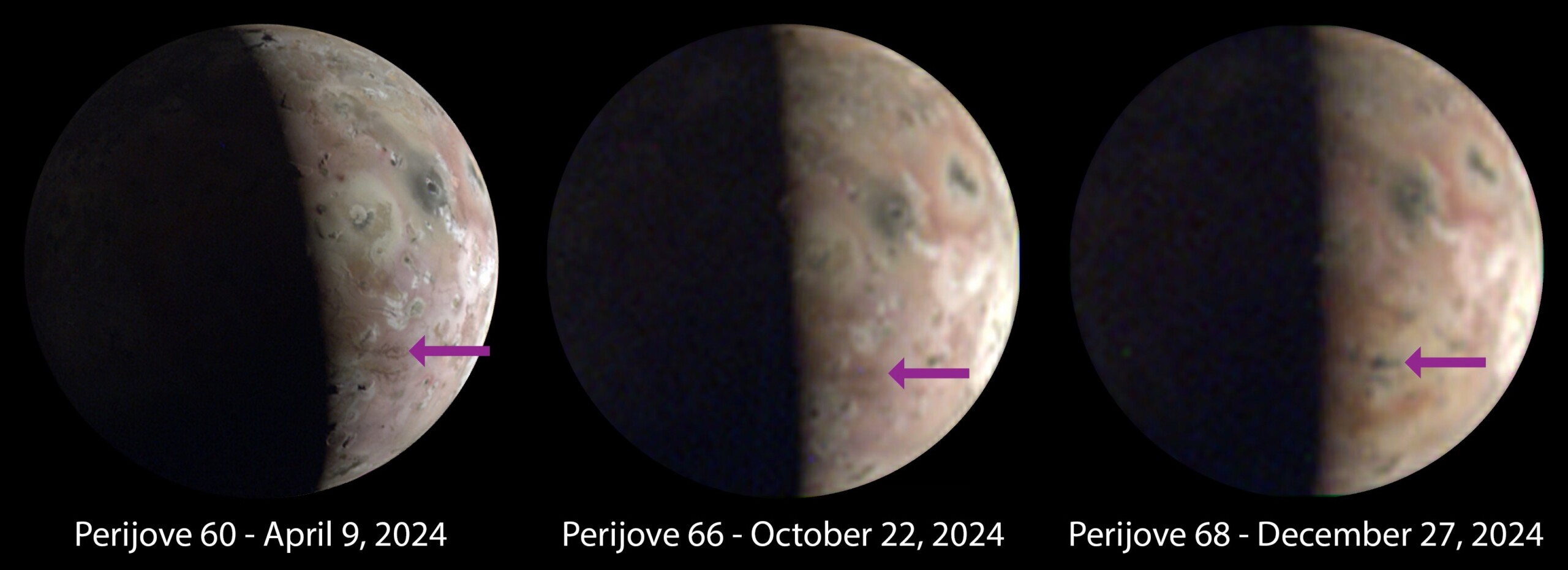

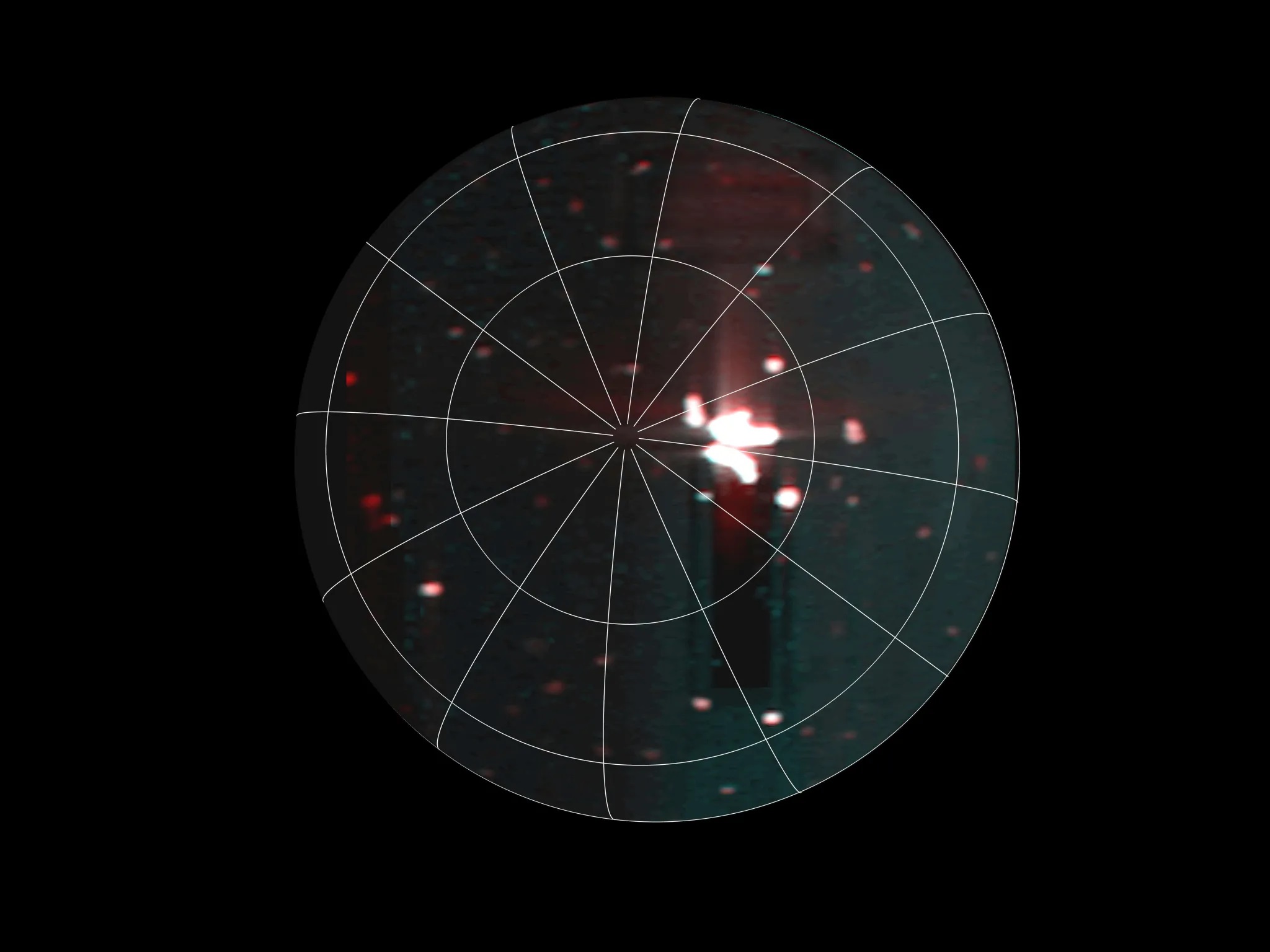

By comparing data from several Juno flybys of Io from 2024, scientists noticed a massive hotspot on the moon’s south pole detected by Juno’s infrared camera. They were able to match this to corresponding changes in the appearance of the surface of the moon, indicating a rather traumatic eruption had indeed taken place on the tortured world.

Analysing the eruption, NASA scientists concluded that the hotspot is about 50% larger than Tasmania and is spewing about 6x more energy than the entire worlds power consumption.

Where does all this energy come from? It’s Jupiter’s enormous gravity at work. Io is the closest large moon to orbit Jupiter. Its orbit isn’t perfectly circular but instead is elliptical. This means sometimes it is closer to Jupiter, sometimes further away.

Consequently, the strength of Jupiter’s gravity that Io feels gets stronger, then weaker and stronger again in a repetitive fashion. This varying strength alternately stretches and relaxes the moon in a process called tidal deformation, which creates an enormous amount of heat as the material in Io is forced to move around and rub against itself, somewhat akin to bending a paper clip or metal pipe back and forth. Ultimately this heating melts parts of Io’s interior, which then erupts through walk points in the surface.

Io is a fascinating world to look at, you can even see it around Jupiter in the night sky with only a modest telescope, but it is certainly not a contender for a nice place to live.

Meanwhile in the Scitech Planetarium

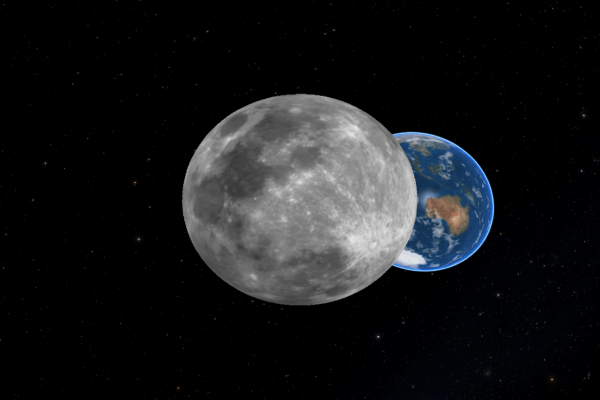

We are launching a new all-ages show A Little Trip to the Moon.

Join in as we count down, take off and travel through space to our nearest cosmic neighbour. In this spectacular 10-minute voyage we’ll land on the Moon, leave our footprint on the surface and even see moons from around other planets. This show has been created specifically for toddlers and is suitable for all ages.

A Little Trip to the Moon will be playing during Toddlerfest, from Feb 15 – Mar 9.