This article is a speculative piece based on the European Space Agency (ESA) Strategy 2040 plan for the future of space exploration. Dr Orson Sutherland, a program manager responsible for Mars exploration at ESA, shared his expertise and work on multiple ongoing projects.

Orson stresses that, in Mars exploration, “There’s ambition and then there’s reality.”

There are many technical, physiological and psychological challenges to overcome and safety risks to minimise before a manned mission to Mars is possible.

“We have to do it in a way which is responsible,” says Orson. “Even if there are people out there brave enough to take the risk.”

Not So Small Problems

It’s 2046 and blue sky fades to black as your rocket blasts into space.

You release a sigh of relief when the ship’s diagnostics report optimal radiator function. There’s no convection or conduction in space – if your radiators fail, you boil. It’s one of those small problems most people don’t think about.

“There are so many small problems that don’t seem sexy enough when you think about trying to land a big rocket on the surface,” says Orson.

Radiation, dust, biological threats. Those ‘small problems’ are your responsibilities. The media mockingly calls you the Little Things Lead. Among the other astronauts, though, your position is revered.

Credit: Supplied Orson Sutherland

Paving the Way

Your commander jokes about the headlines accompanied by images of colonies made of domes and hallways. As if you could afford to bring a whole building.

Your base has to be underground.

“At about 1.5 metres depth, you get effective full protection, full shielding,” says Orson. Shielding from the deadly solar radiation the Martian atmosphere is too thin to filter out.

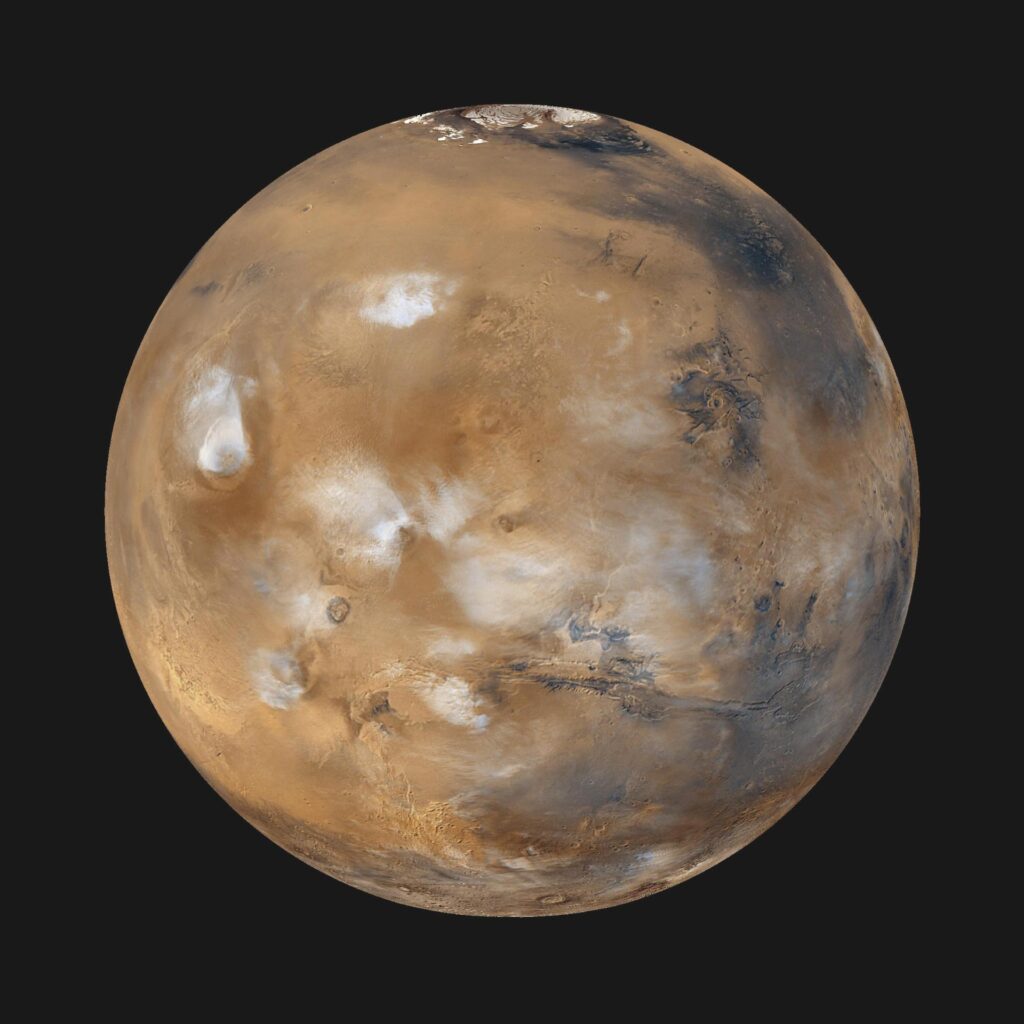

You’re reminded of Rosalind Franklin, the first rover to drill that deep on the surface of Mars. Launched in 2028, it helped pave the way for this mission. The results from the Mars Organic Molecule Analyser (MOMA) were particularly fascinating.

MOMA was designed to analyse samples from beneath the surface for organic molecules. If there is any life on Mars, that’s likely where it will be.

NASA-ESA Mars Sample Return was equally pivotal. Bringing samples to Earth for analysis proved a round trip was possible.

Credit: ESA/Mlabspace, 2020. ESA Standard Licence.

Clashing Ambitions

Your crew fixate on minor course corrections. Mars is a small moving target in a big Solar System.

Missions can only be launched in one short window every 26 months. It is critical that everything goes to plan. If your mission fails, the next opportunity won’t be until 2048.

You recall a number of failed SpaceX launches in 2025 that delayed the company’s efforts to send a humanoid robot to Mars. Mars missions are impossible if you can’t first demonstrate the necessary technology.

This mission is one such demonstration for the next. Although next time, there’s no certainty that all the clashing ambitions will be able to compromise again.

“There is a synergy between colonial ambitions and scientific curiosity. I think we just need to make sure we do it in a way that both views are respected and it’s in the best interests of all humanity,” says Orson.

“I can’t believe that we would colonise and not want to understand.”

That’s the sentiment that led to this mission.

While some want to colonise and others want to understand, most fall somewhere between.

The desire to discover the origins and evolution of the Solar System tempers even the biggest egos.

Science All the Way Down

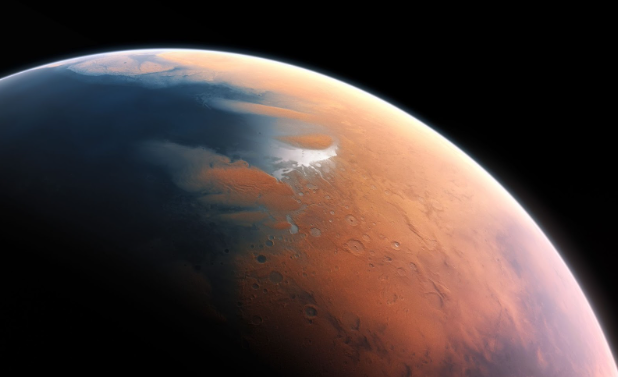

The geology of Mars, which once had liquid water, will reveal many of the secrets of that evolution. There’s a buzz of excitement among the crew about what you might discover on the surface of the Red Planet.

The science has already begun. You’ll be participating in various experiments testing the effects of prolonged space flight throughout the 9-month voyage to Mars.

That’s a long time to contemplate your hopes for this mission.

“I have no doubt we will achieve [colonies on Mars],” says Orson. “That is not the question. The question is when and under what circumstances.”

What are your circumstances? Do you want to own or learn?

Regardless of ideals among the crew, you all agree on two essentials of the mission.

Credit: NASA/JPL/MSSS

Bureaucracy in Space

First and foremost, respect the COSPAR rules. Minimise your footprint on Mars to prevent environmental contamination.

Respecting COSPAR means keeping track of everything you come into contact with to ensure you maintain Earth’s biological integrity when you return.

“I think we as Europeans want to ensure that we can maintain a pristine environment where we’re going,” says Orson. “Whether that’s Mars … [or] whether that’s anywhere else in the Solar System or beyond.”

Your biggest challenge will be the second essential.

“You’re going to need to be able to get the resources in situ to survive and to come back,” says Orson.

That means water, nutrients and building materials need to come from Mars.

Some in your crew see in situ resource utilisation as a fascinating experiment. Others see it as a thrilling challenge.

To enhance humanity’s understanding of Mars and its potential to support ancient life and future colonies, you’re all ready to work together.