In early March, Saturn’s moon count stomped ahead of the rest of the Solar System with announcements bringing the ringed planet’s total moon count to 274 natural satellites. This is almost twice as many as all the moons around all the other planets added together, totalling ‘only’ 142 moons, of which 95 orbit Jupiter.

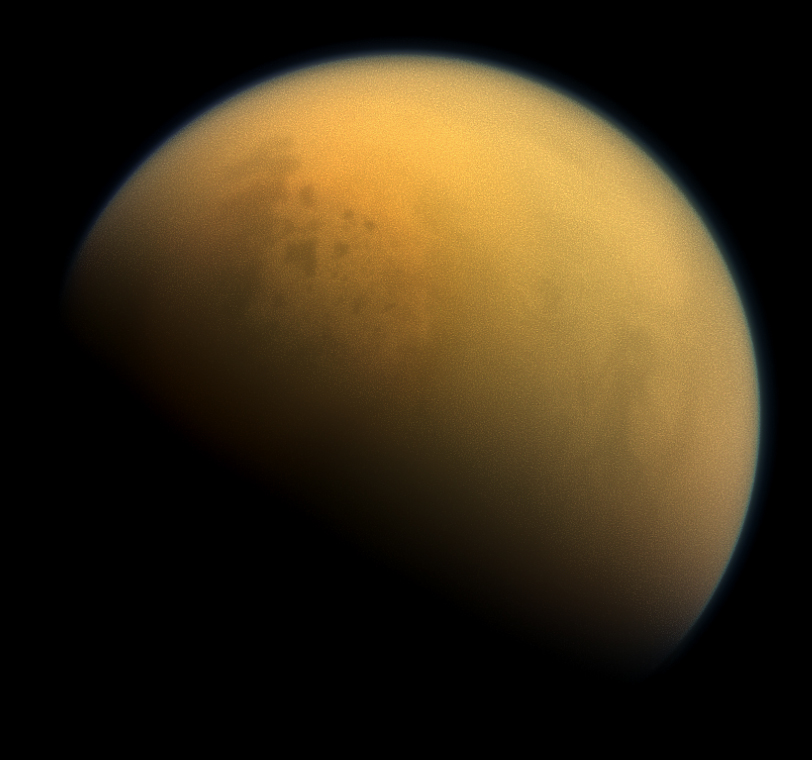

Saturn is already well known for its interesting moons. Its largest moon Titan, about 50% larger than Australia, is the only moon in the solar system with an atmosphere, and the only other object in the solar system aside from Earth with lakes and rivers on its surface. Unlike Earth however, these lakes are made of liquid methane – literally rocket fuel, while the atmosphere is made mostly of nitrogen.

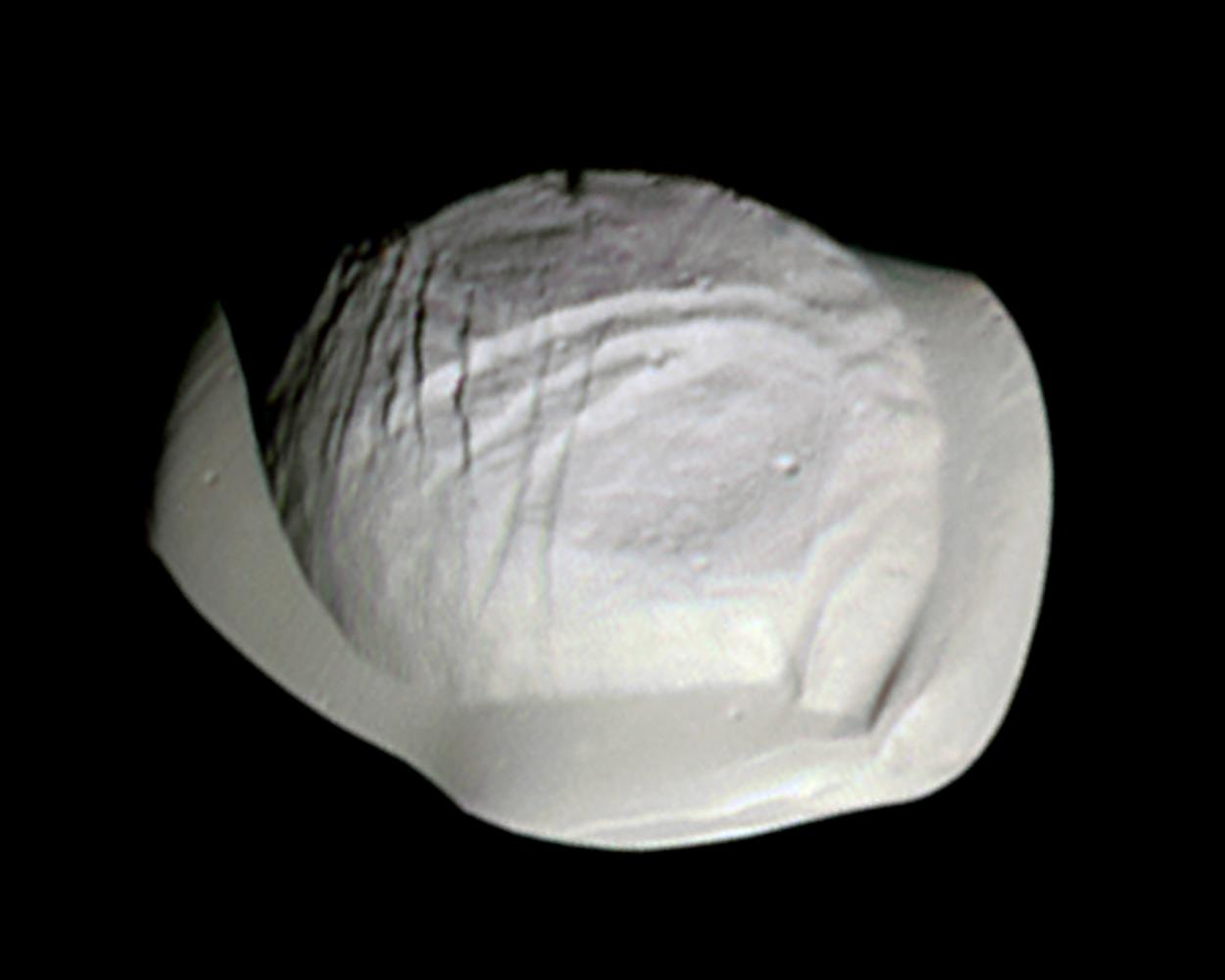

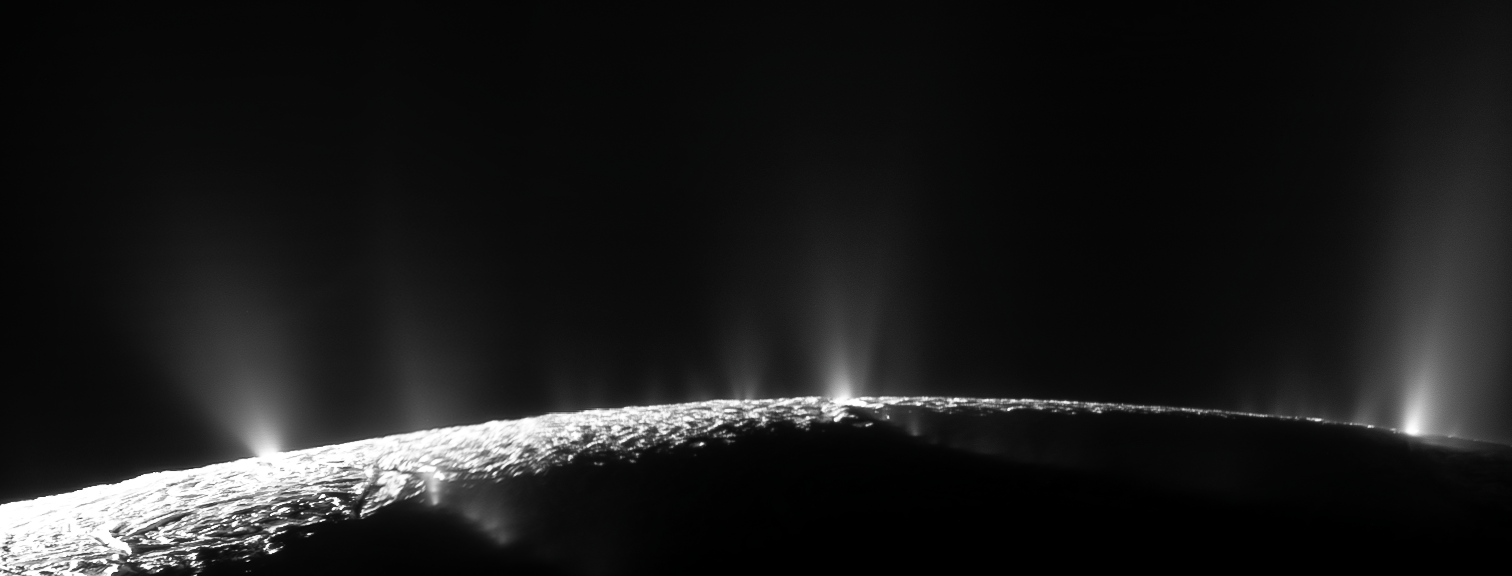

Titan is (arguably) edged out of the ‘most interesting Saturnian moon’ seat by Enceladus. This icy moon, about as wide side to side as the distance from Perth to Kalgoorlie, is known to have subsurface oceans of liquid water beneath its tortured frozen exterior. The surface of Enceladus bears large cracks, somewhat like the fragmenting of Earth’s surface into tectonic plates. At weak points in the surface, molten ice (aka water) can force through and erupt as ice volcanos.

Titan and Enceladus are part of a group of 24 Saturnian moons classified as regular moons. Most of these moons orbit almost directly above Saturn’s equator and move prograde, in the same direction that the planet rotates. Astronomers generally think the regular moons formed with Saturn billions of years ago as the planet coalesced from the primordial disk that formed our solar system.

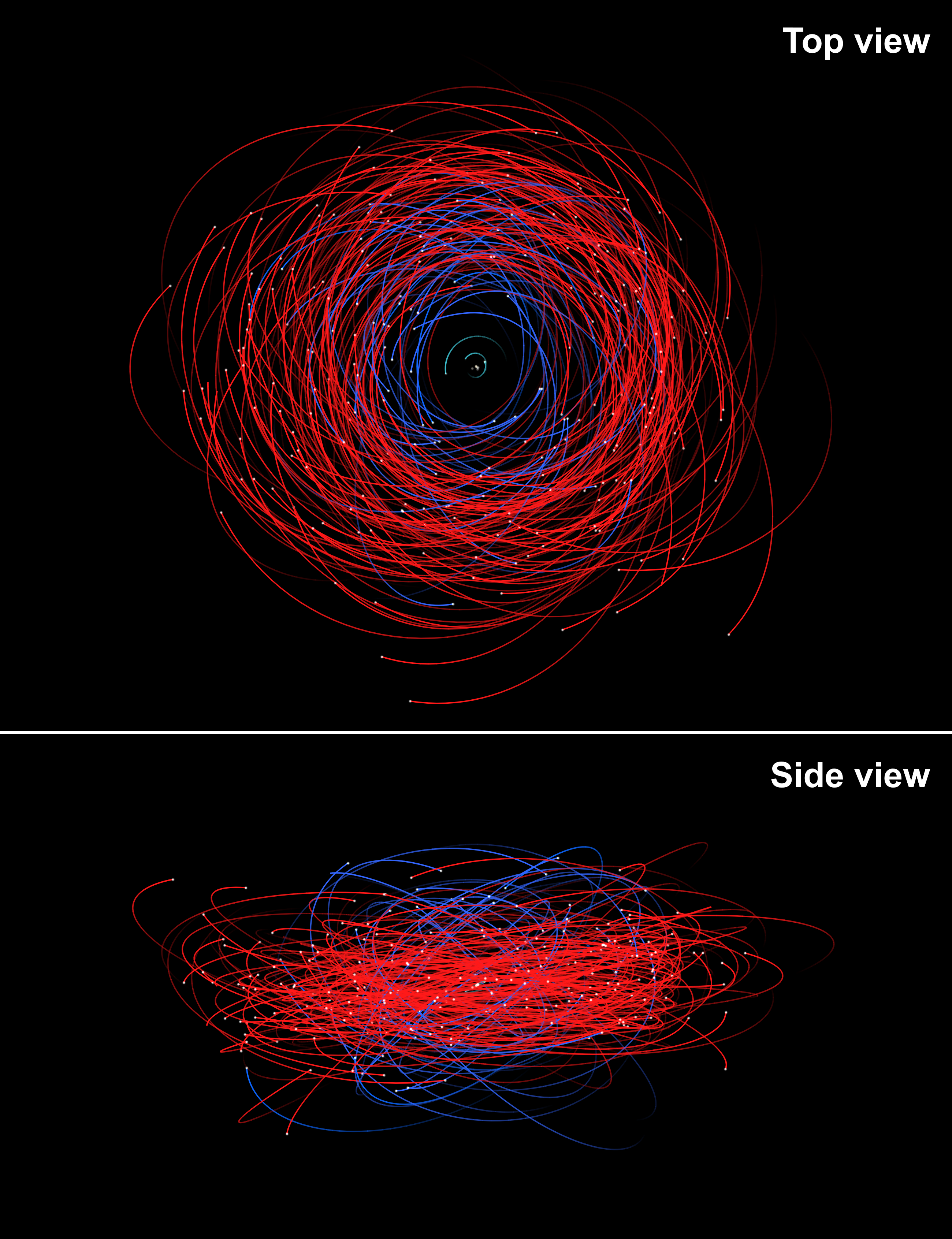

Regular moons are so named to distinguish them from remaining 250 moons, classified as irregular moons. The orbits or these irregular moons are much more scattered, often greatly tilted to Saturn’s equator, many of them orbiting retrograde – in the other direction to Saturn’s rotation – and just generally being messy. All 128 of the newly announced moons are irregular moons.

Credit: Nrco0e – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0,

It is worth pointing out that the newly announced moons were actually discovered a while ago. They were picked out of observations mostly performed between 2019 – 2023, but some data goes as far back as 2004. The reason they are in the news now is they have been officially recognised by the International Astronomical Union, the governing world body on astronomical matters.

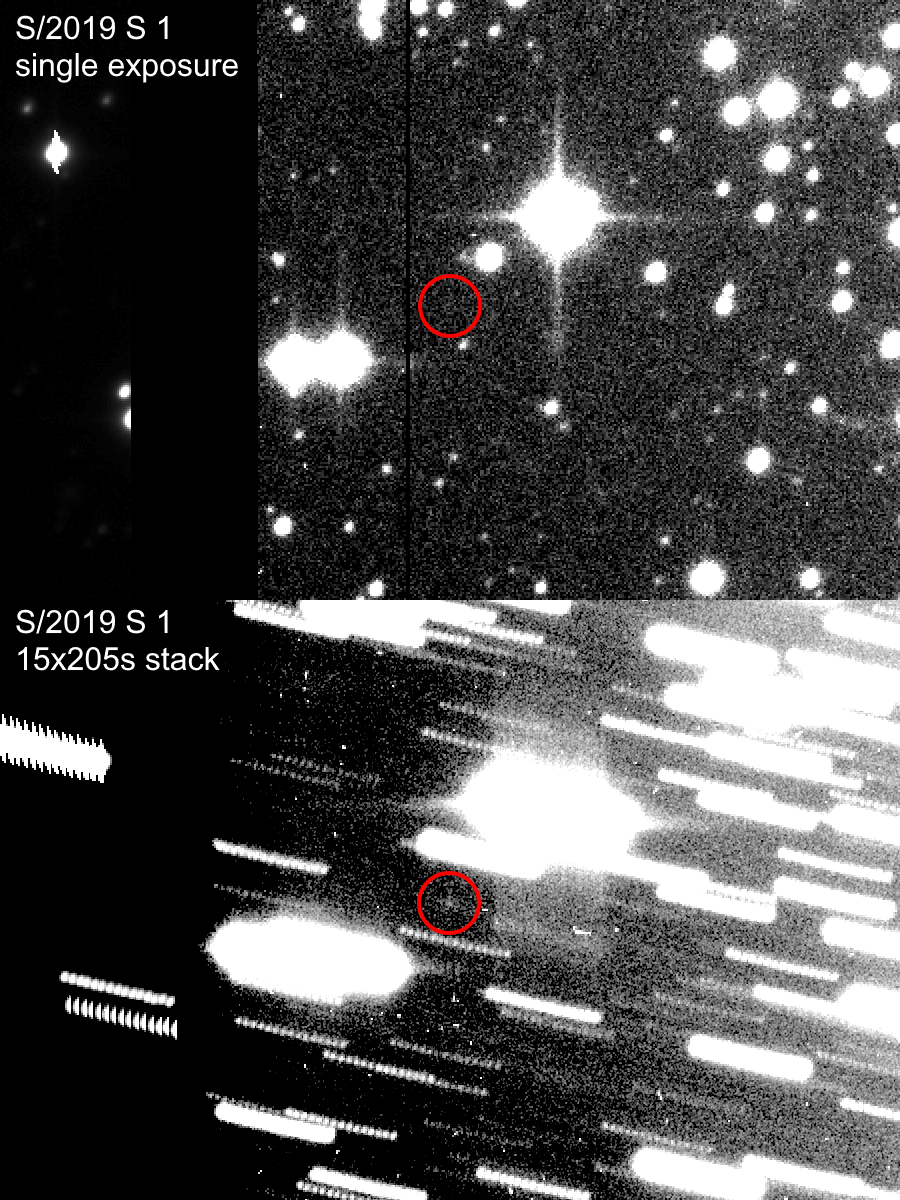

These new moons are tiny, only a few km across, making them extraordinarily difficult to spot. Astronomers use a technique called ‘shift and stack’, basically a fancy way of saying adding the data together (stack) while accounting for the motion of Saturn (shift). In any one image you won’t see much, but adding lots of observations together allows a weak signal to stand out from ambient noise.

Finding new moons of Saturn isn’t just a mindless intellectual exercise. The point is to look for patterns and interestingly, most of Saturn’s irregular moons have uncorrelated orbits, giving us clues to its history. If the irregular moons were formed by, for example, a single large moon breaking into pieces, then we would still expect them to have similar orbits. While there are some similarities between smaller subgroups of irregular moons, the lack of overall correlation suggests that the irregular moons of Saturn come from possibly many smaller moons involved in breaking apart or violently colliding, or both, in either order. There is also the possibility some of them are captured asteroids. Teasing out the history of the solar system from a few faint pixels in a photograph is some powerful science.

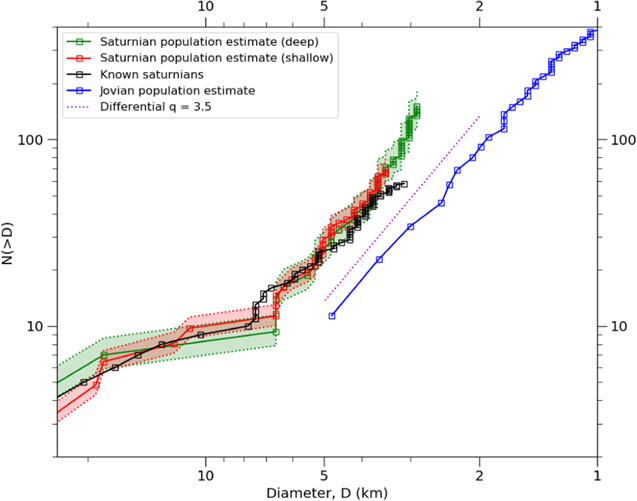

This probably won’t be the last we’ll hear about moons around the outer planets but even based on what we have discovered so far, an interesting pattern emerges. When you plot how many moons of a given size Saturn has compared to Jupiter, Saturn still leads by more than 3 times for the data available, suggesting that Saturn intrinsically has more moons than Jupiter, another interesting clue that might be hinting at something deeper.

This all does beg the question of what is a moon? And how small is too small? At the moment there is no consensus among astronomers where to draw the line for what is a moon. Most people would agree that the trillions of particles of ice that make up Saturn’s rings probably don’t fit the bill of being called a moon. Somewhere in there is an answer, but more science is needed to really understand what makes moons stand out from the rubble.