Intelligent life, if it’s out there, would not use the international system of units.

Metres, kilograms, seconds—all of these standards used to measure everyday life were originally taken from observable features of nature.

The metre was originally defined to be one-ten-millionth (that’s 1⁄10,000,000) of the distance between the North Pole and the equator. A kilogram was originally the weight of a litre of water at freezing point, but that proved too variable. Now it’s defined by Le Grand K, a metal cylinder secreted away in a vault outside Paris.

So unless some alien colony out there is obsessed with Planet Earth and is trying to emulate everything we do (please, no, don’t), they’ll likely have developed their own standards for quantifying whatever world they’re living in.

Which could make it a little tricky if we ever need to communicate with them in this way. After all, even humans can’t get it right sometimes. In 1999, the Mars Climate Orbiter disintegrated in Mars’ upper atmosphere when software (supplied by a contractor) calculated the force produced by the probe’s thrusters in US customary units when NASA was expecting measurements in metric.

(Incidentally, the next time we put men and women on the Moon, all measurements will officially be metric.)

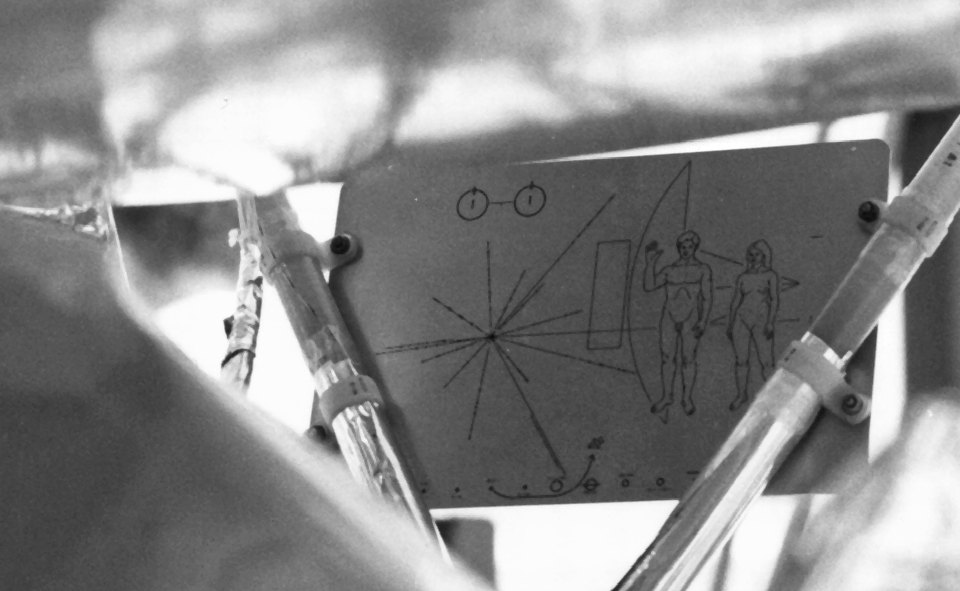

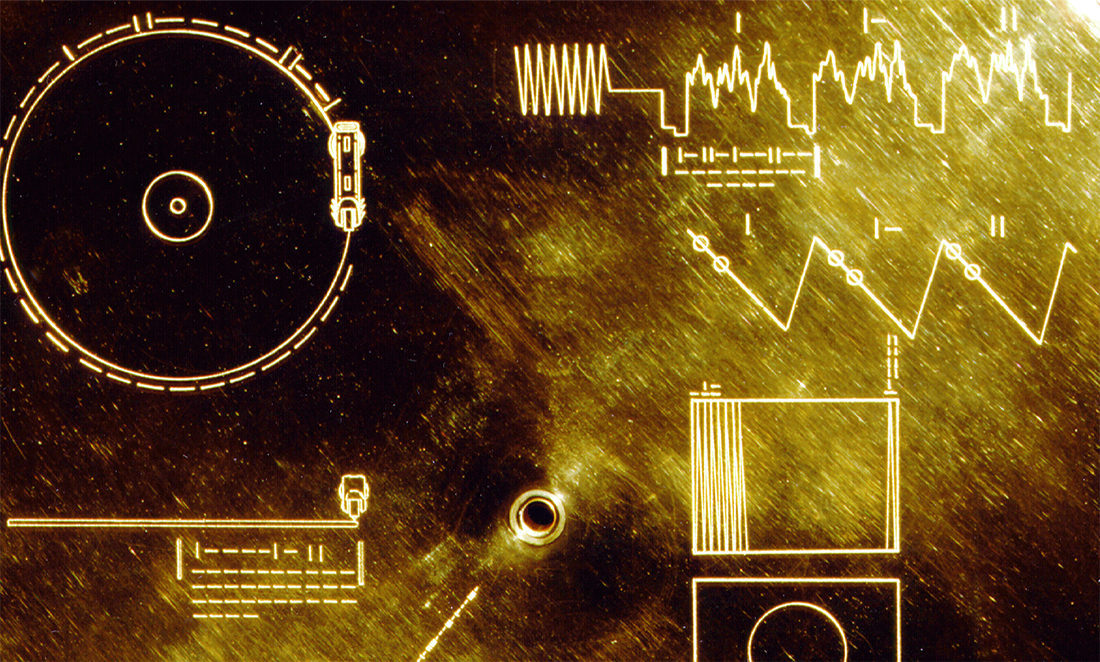

The Golden Record that NASA sent up with the Voyager famously carries the definitive soundtrack of Planet Earth. But it also carries encoded pictures.

In the same way that we initially based the metric system on measurements of nature, these pictures use the most common element in the universe to define seconds, metres and grams. The time, size and scale of our Earthling lives will be communicated to aliens through a simple sketch displaying the mass and energy of a hydrogen atom.