Tara has been studying rocks in an area of the Pilbara called the Dresser Formation where fossilised stromatolites—structures built by microorganisms—have been found. Besides extending the record of life on land by up to 580 million years and hot springs by 3 billion years earlier than previously thought, these findings may also help us in the search for life on Mars.

You’ve probably heard that Mars and Earth share a few similarities, including evidence of water and volcanic activity at different stages in time (more on those in a minute). Another of these similarities is age. These fossils are around 3.48 billion years old, which is about the same age as many of the rocks that cover the surface of the red planet.

Mars rocks

“A lot of Mars’ crust is about the same age as the Pilbara deposits,” Tara said. “Data collected from the Spirit rover has identified ancient hot springs on Mars, and rocks in the Pilbara represent a similar environment.”

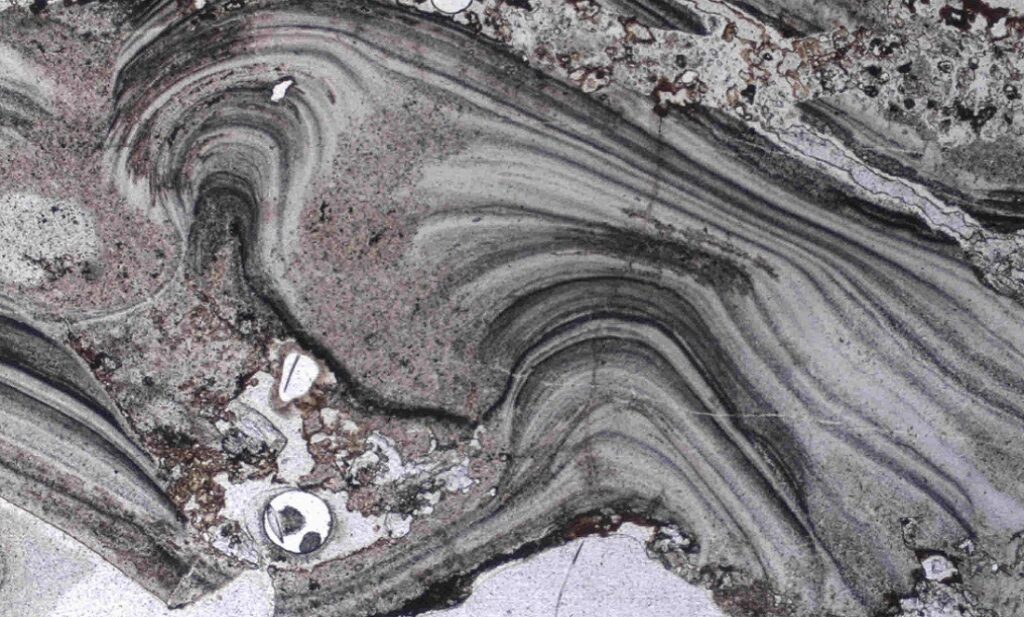

It was previously thought, from studies carried out in the late 70s and 80s, that the stromatolites were fossilised in calm, shallow waters similar to those of Shark Bay. More recent discoveries have shown that pretty much the opposite is true—that they were actually formed in a volcanic environment.

Another piece of the puzzle was the presence of geyserite, a type of rock found around the edges of hot springs and, you guessed it, geysers.

Geyserite is made of a mineral called silica, and geysers are full of hot water that is silica rich. These silica-rich hot-spring systems could provide a link between preserved fossils in the Pilbara and Mars.

“Our findings imply that, if life ever developed on the red planet and it is preserved in ancient hot springs on Earth, then there is a good chance it could be preserved in ancient hot springs on Mars too,” Tara said.

“If we’re going to search for evidence of life on Mars, shouldn’t we look at similar rocks?”

Visiting NASA

NASA is set to send a rover to Mars in 2020, and earlier this year, Tara and her fellow researchers visited NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, where three sites were chosen for the rover to explore.

One site on Mars, Columbia Hills, is now on the list, and the rover could be going there to look for fossil life.

“The other two sites contain evidence for past aqueous (water) environments or ancient lake deposits,” Tara said, “but the preservation of fossil material in these environments at such an ancient age is highly unlikely. The hot spring systems of Columbia Hills are a much more viable target in the search for life on Mars.”