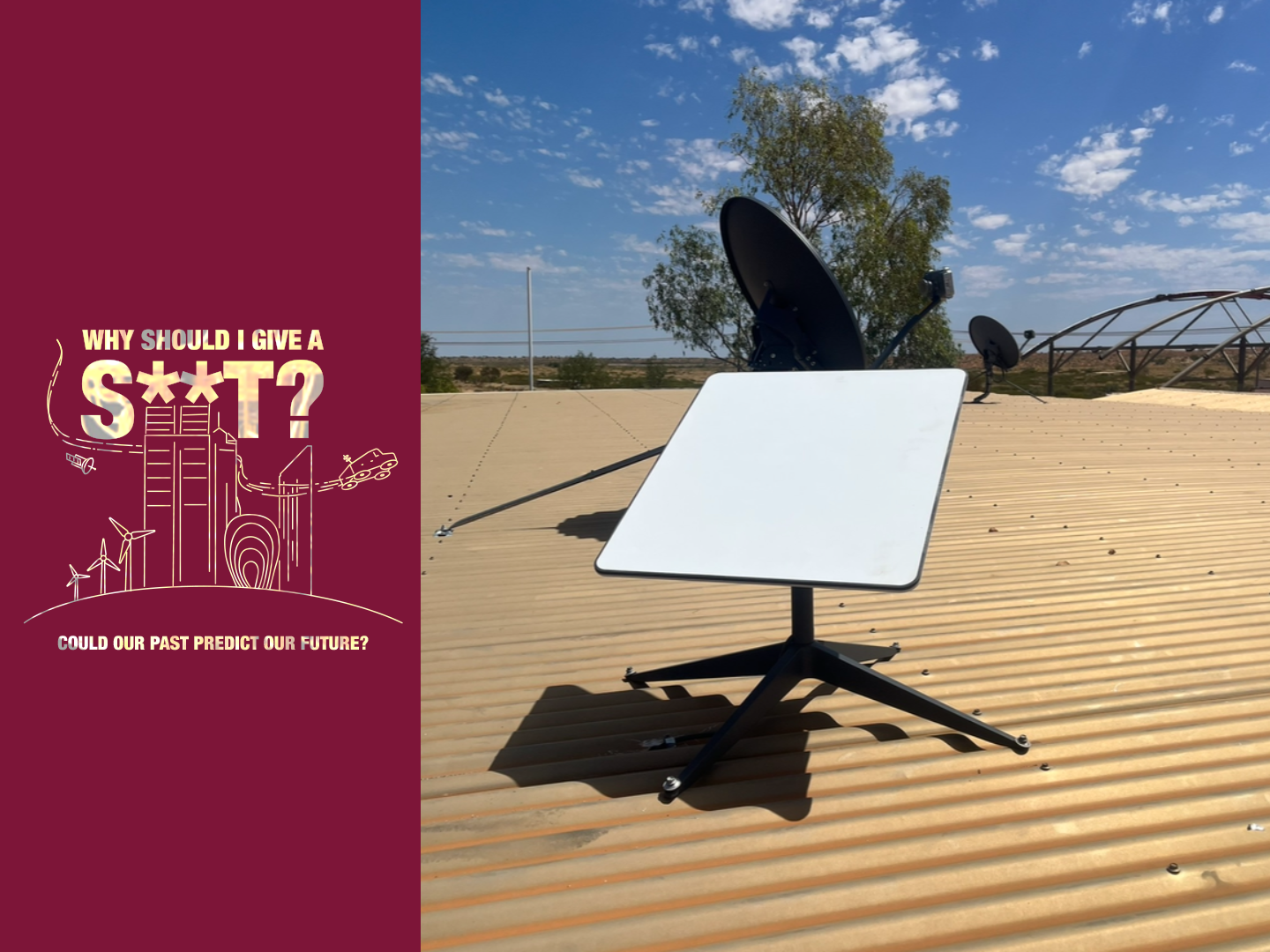

Deep in Martu Country, the Rawa Community School has a new addition. Perched on the roof is a squat, sealed rectangle. Curved underneath, flat on top and angled towards the sky, it’s a sight becoming increasingly familiar in regional Australia: Starlink.

“As a teacher, reliable Internet was pretty game-changing for engaging students,” says Mr Jamparri, who has taught at Rawa in Punmu since 2022.

“Although the curriculum at Rawa is focused on getting kids out on Country and teaching language, having reliable access to the Internet has been vital for supporting engagement of our students inside the classroom.”

It’s increased access to everything from documentaries to Mathletics – resources that are taken for granted in the city.

It’s been a huge complement to the school’s two-way learning approach, meeting the kids and the community where they are.

“I know for my class I wanted to introduce Minecraft education, which is a game that a lot of the kids love playing at home and playing for fun,” says Mr Jamparri.

“With Starlink I could actually bring that into the classroom.”

It’s fast, reliable, and making a difference. But how does it work?

Closer to space than anywhere else

As anyone who has struggled to get decent wifi in their back room knows, the closer you are to the internet, the faster and more reliable it is.

“There were definitely days, with that old connection, where the internet would get blacked out just from the weather,” says Mr Jamparri.

“They’re definitely harder, those days, because you didn’t have as many tools to engage students.”

Caption: Punmu is the second most remote community in Australia – it’s closer to space than anything else.

Credit: NASA/Google Maps

Those old connections used satellites that were locked in a ‘geostationary’ orbit.

At that precise altitude, spacecraft orbit the Earth in exactly 24-hours as the planet turns beneath them, meaning they always point at the same part of the planet.

While the upside is you only need to build one satellite to cover a given area, the drawback is the satellite has to be 35,000km away to work.

Starlink takes a different approach: Closer satellites make for a much faster connection.

The Starlink satellites orbit just 550km up. For comparison, the nearest major town to Punmu, Port Hedland, is 600km away.

That low altitude is why Starlink works so well for remote communities. Towns like Punmu are closer to space than anywhere else.

At that height, satellites zip overhead in just a few minutes. To ensure when one disappears over the horizon, another is already in range, you need more of them.

Thousands more.

That’s No Moon(rock)

According to Dr Ellie Sansom, Global Fireball Observatory director, that’s what makes ‘megaconstellations’ like Starlink different from anything we’ve seen before.

“The big thing with Starlink is just the quantity, I think, of how many there are up there,” says Ellie.

Ellie helps run a network of cameras in the outback whose main job is to spot meteors as they enter our atmosphere, and track down the meteorites they drop.

But increasingly, they’ve been seeing something else too.

Starlink satellites orbit so low that they skate through the top of the atmosphere. They need fuel to stay up, and – increasingly importantly – to dodge other satellites. When that fuel runs out, or they otherwise break down, it’s re-entry time.

Caption: A re-entering spacecraft streaks across the sky in an image captured by the Desert Fireball Network

Credit: Supplied Desert Fireball Network

“These satellites have a nominal five-year lifetime,” says Ellie. “They can’t stay up there forever.”

Starlink’s first big batch of satellites went into space in 2020, which means many are due to return this year.

“Normally we get one to two re-entries in Australian airspace per year,” says Ellie.

“The current estimate is that by 2030 there will be 1400 objects per year.”

“And a lot of them are planned to come down in unpopulated areas of Australia.”

‘Unpopulated’ — except for remote communities like Punmu.

Dice and fireballs

That’s not to say Mr Jamparri and his students will be dodging falling spacecraft whenever they’re out on Country. Most will end up in the ‘spacecraft graveyards’ in the Indian and Pacific oceans.

But as Ellie points out, things don’t always go where they should – and when they don’t, Australia is smack bang in the middle.

Caption: WA is no stranger to space debris either, this fragment from a ‘spacecraft graveyard’ washed up in 2023

Credit: Scitech

“When you have a large number of events with a low risk, that adds up – suddenly that could be a satellite a year,” she says.

For a preview of what that might be like, she points to the 2022 re-entry of a SpaceX capsule over New South Wales.

While the cameras saw chunks of capsule material end up in an inhabited area, Ellie’s team, using a weather radar, detected much more.

Ellie says they saw a dust cloud covering at least 6000km2 spread across a national park and Canberra’s water catchment. Yikes.

Unanswered questions

Regardless of how you feel about Starlink, or its deeply problematic owner, megaconstellations appear to be here to stay.

SpaceX competitor Amazon Project Kuiper, China’s Guowang, and European OneWeb, are all gearing up to compete for Starlink’s estimated USD $8 billion in annual revenue.

The promise of connection is just too useful to ignore.

“Because we had reliable internet, that actually became a big engagement for the community because students and teachers could access it while they’re up at the school,” says Mr Jamparri.

“We could also get them connected to important services like banking and Centrelink and other things, and do all that kind of life admin stuff that [they] often wouldn’t be able to do at home.”

Ellie and the team use Starlink for fieldwork, and she agrees it’s made things easier.

“It’s been really useful to be able to access the supercomputer on field trips instead of having to take equipment out with us,” says Ellie.

But while the effects on our sky are well documented, the effects on our planet aren’t.

“People assume that surely it’s been well thought out and planned,” says Ellie.

“The thing is, we don’t know. We don’t have a way of actually verifying that they came down in unpopulated regions, or if they fell short, or that they came down at all.”

“There’s a lot of unanswered questions that people aren’t asking because they just want to stick with the awesomeness of what it’s doing. And I think there is a responsibility to be asking those questions.”