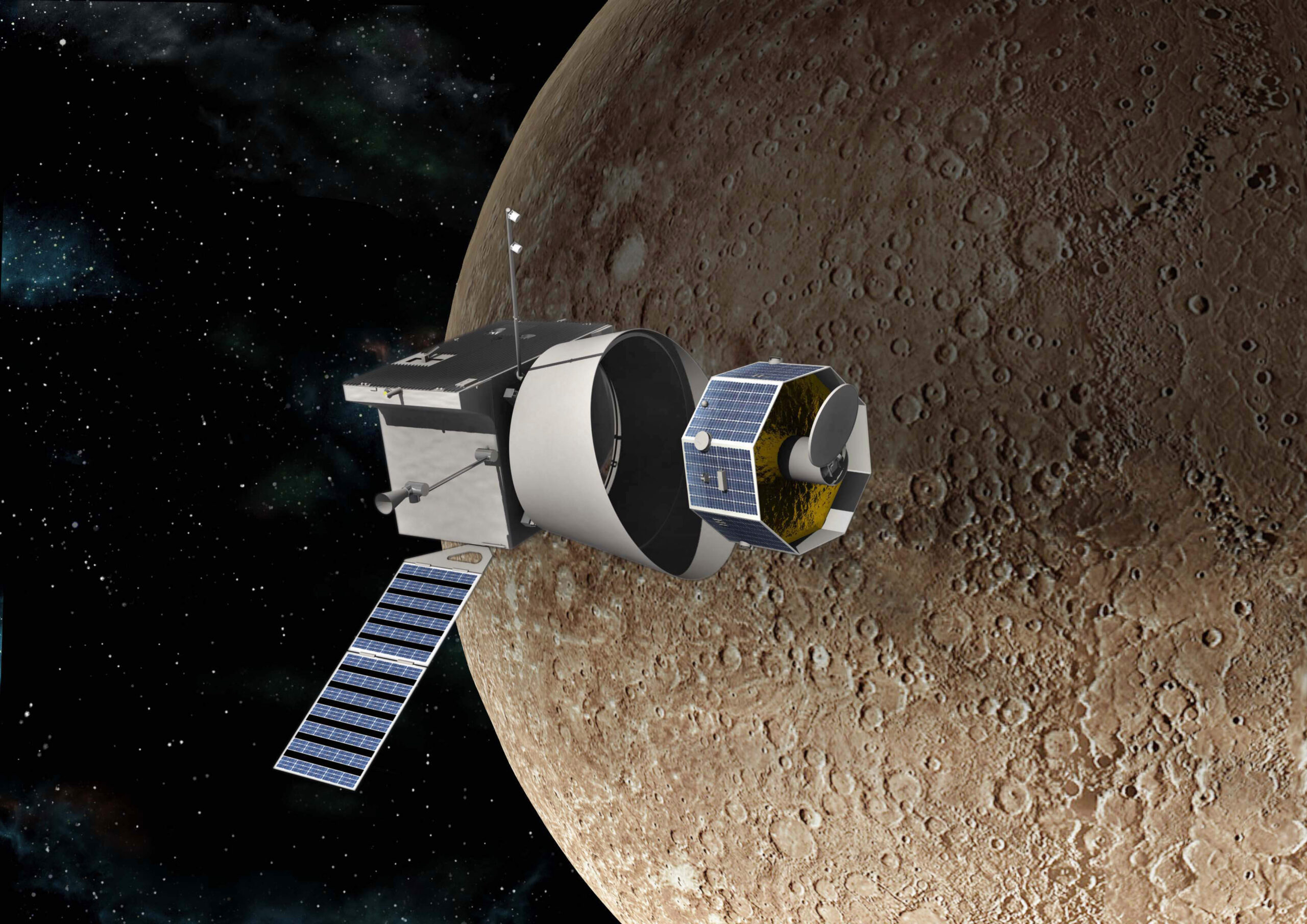

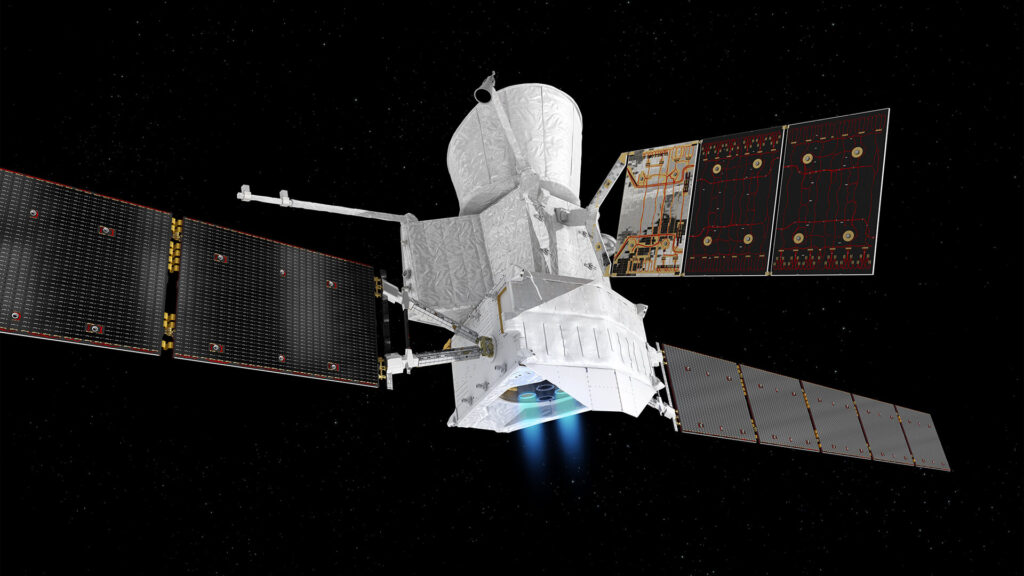

The BepiColombo spacecraft, a joint European Space Agency (ESA) and Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) will be completing its 6th flyby of Mercury on Jan 8. The mission, launched in 2018, is actually two separate spacecraft tied together – the Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) built by ESA and the Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO) built by JAXA.

Mercury is a surprisingly under-studied planet because it is actually quite difficult to make detailed observations from Earth. It is only ever visible near the horizon at sunrise or sunset, and its proximity to the Sun means if you point a telescope at it, you’re also pointing close to the Sun, confounding observations.

Sending a spacecraft to Mercury is not any easier. Since going to Mercury means getting closer to the Sun, the journey is basically “downhill” the whole way and the Sun’s strong gravity imparts energy to an approaching vessel. Spacecraft pick up an enormous amount of speed as they approach Mercury, and you have to find a way to lose that excess velocity. Think of it like trying to safely jump off the roof of a house – you need to lose the speed before you hit the ground or bad things will happen. Some quick maths shows that if a spacecraft travelling to Mercury was to try to lose this speed simply by burning chemical fuel in its engines, it would take more fuel than it takes to travel to Pluto. The dwarf planet Pluto is about 40 times further away from Earth than Mercury, but it takes less fuel to get there. Orbital mechanics is weird like that (you should really click that link)

For this reason Mariner 10 – the first of only two spacecraft to ever visit Mercury previously – was only intended to do a single flyby of the planet in 1974. That was until Italian scientist Guiseppe ‘Bepi’ Colombo cleverly calculated how the spacecraft could instead fly close to Venus and use the planet’s gravity to ‘slingshot’ toward Mercury, losing some of its excess speed and saving a lot of fuel, ultimately allowing three flybys of Mercury instead of one. This technique, called a gravity assist manoeuvre, is commonplace these days but was the first of its kind in the 1970s. It was by using multiple gravity assist manoeuvres that NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft became Mercury’s second visitor in 2011, ultimately orbiting the planet until 2015.

An enormously complicated series of gravity assist manoeuvres is allowing BepiColombo to approach Mercury today.

Ultimately, BepiColombo will have made use of 9 gravity assists: 1 Earth, 2 Venus and 6 Mercury, and on Jan 8, 2025, it will complete its 6th and final Mercury flyby. This last flyby of Mercury will rob the spacecraft of enough speed that its miniscule ion engines (providing a whopping 30 grams of thrust) will be able to put the spacecraft into orbit around Mercury by December 2025. After this seven-year journey to lose enough speed to get into orbit, the BepiColombo science mission begins.

At this stage the MPO and the MMO will separate and use their own propulsion systems to go into slightly separate orbits. The MPO will go in a close orbit to get good views of the surface of the planet, while the MMO will stay in a higher orbit to better sample different parts of Mercury’s magnetic environment.

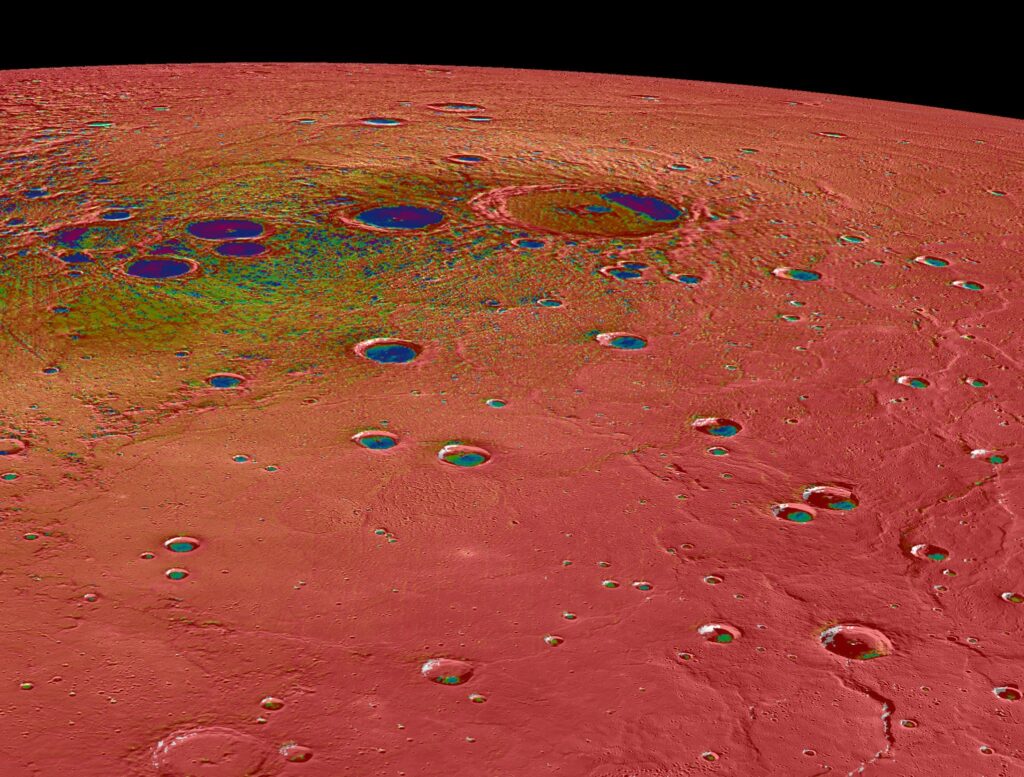

The Mercury Planetary Orbiter carries a wide range of instruments to study the planet. Several cameras and a LiDAR system will give detailed information of the surface, while 4 different spectrometers will analyse the chemical composition at the same time, and all these things combined will give a comprehensive 3D map of the surface of Mercury, complete with mineral distribution and chemical composition. Meanwhile, particle detectors will sample Mercury’s miniscule atmosphere to see how it behaves, and as this is happening, accelerometers on board the MPO will also detect tiny changes in the spacecraft’s motion as the planet’s gravity tugs it to and fro, allowing scientists to work backwards and map the interior distribution of mass inside the planet.

While the MPO is busy studying the surface, the Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter will be studying charged particles, plasma waves, dust and the general magnetic environment surrounding the planet, to determine the origin and behaviour of Mercury’s magnetic field. During BepiColombo’s 3rd flyby in June 2023, instruments on the MPO collected enough data in 30 minutes to provide fascinating early models of Mercury’s magnetic environment.

Ultimately the goal of the mission is to learn a lot more about the planet in general. Does Mercury have a solid or liquid core, or both? Where are the predicted large amounts of iron? What is the origin and behaviour of its magnetic field? Is the planet geologically active today? Do those permanently shadowed craters at the north pole of Mercury actually contain water ice? Yes, seriously, the closest planet to the Sun may have polar ice ‘caps’.

Time will tell what BepiColombo will discover. For now, it will wave at Mercury as it completes its 6th and final flyby on Jan 8. We’ll catch up with it later next year when it goes into orbit.

‘Bepi Colombo Waves at Mercury’ is an exert from ‘The Sky Tonight: January 2025’ originally published by scitech on 01.01.2025.