With planes grounded and lockdowns around the world, you might be hoping 2020 has come with a silver lining of a drop in global carbon emissions.

And you’d be right – emissions are down.

But there’s a problem.

When carbon emissions drop because of an economic recession, they tend to rebound, often to levels higher than before the crisis.

And it’s too early to tell if that will happen this time around.

Peak lockdown

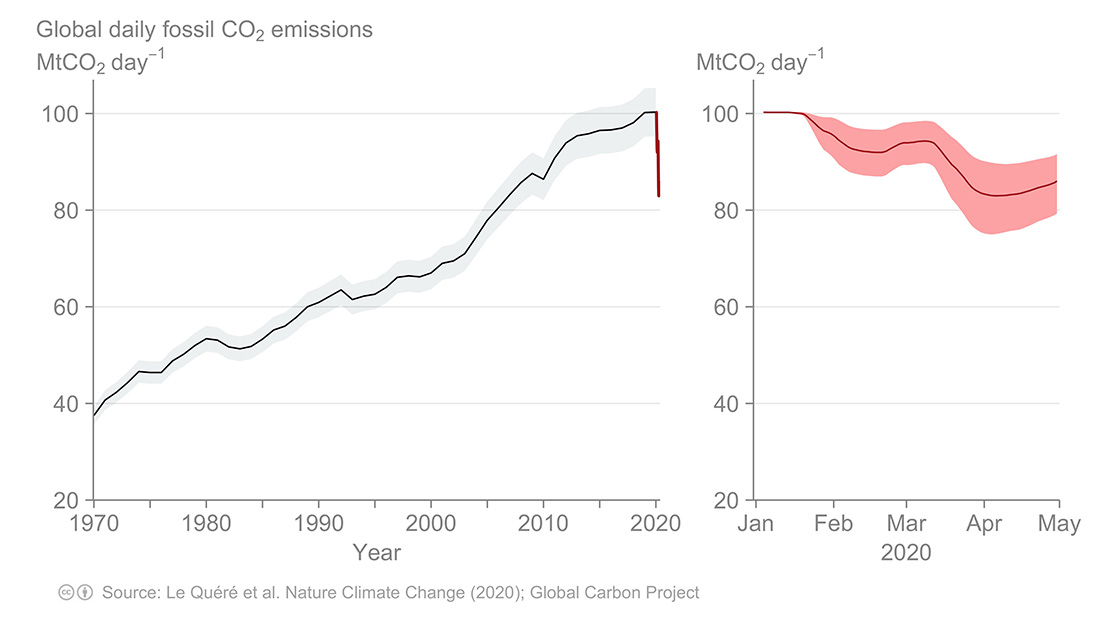

A recent Global Carbon Project study tracked how the pandemic has influenced daily emissions.

The researchers looked at 69 countries – including Australia – that account for 97% of global emissions.

They found that, at the peak of the decline in early April, emissions were down 17% compared to an equivalent day in 2019.

CSIRO researcher and Global Carbon Project Director Dr Pep Canadell says the decreases were largest in China, followed by the US, Europe and India.

“The peak 17% daily decline on 7 April was because China, the US, India and all other major carbon-emitting countries were all in a high level of lockdown at the same time,” he says.

What about all the planes not flying?

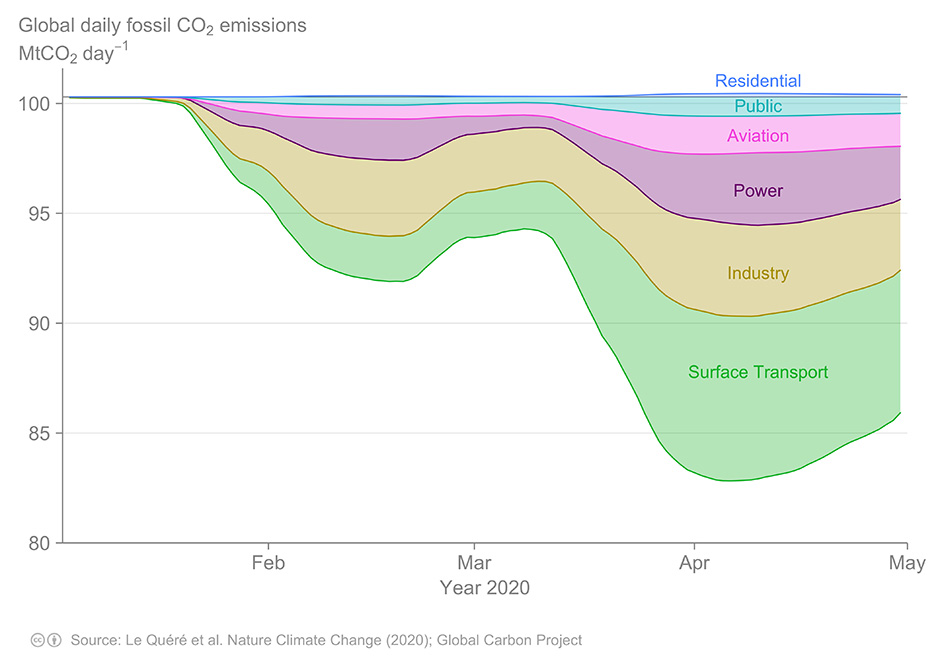

By early April, the global aviation industry had seen a 60% decline in emissions compared to 2019, according to the study.

That represents 1.7 megatonnes of carbon not finding its way into the atmosphere.

But aviation produces less than 3% of global emissions.

So grounded planes were only responsible for about a tenth of the total drop.

The biggest contributor to reduced global emissions was actually fewer cars and other vehicles on the road.

This was followed by a slowdown in power generation.

At the same time, there was a small increase in emissions from the residential sector as people stayed at home.

The study estimated in May that, if countries remained in various levels of lockdown until the end of 2020, emissions would be down 7.5% for the year.

But if sweeping restrictions lifted in mid-June, the decrease would be limited to 4.2%.

Ripe for a rebound

Sounds good, right?

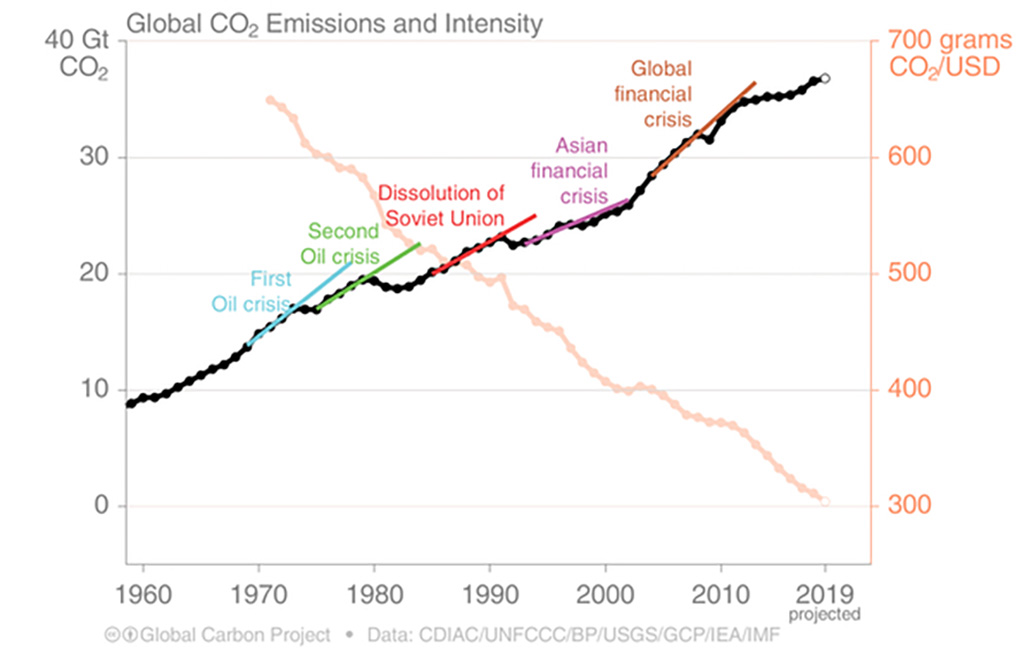

The problem is that, historically, these drops haven’t been maintained.

In 2009, for instance, at the height of the global financial crisis, emissions fell 1.4%.

But less than 2 years after Lehman Brothers’ collapse, emissions were heading north again.

In 2010, emissions surged a massive 5.9% – much higher than the long-term average of about 2% growth a year.

A similar rebound effect was also seen following the 1973 oil crisis, the 1997 Asian financial crisis and other economic shocks.

This could be because of subdued fossil fuel prices or stimulus spending on energy-intensive activities such as construction.

Another theory is that businesses don’t have the cash to invest in clean energy after a recession.

Changing habits

Of course, this crisis is different. It’s born of a health emergency rather than stress in global financial markets.

What we don’t know yet is the extent to which the pandemic will change our lifestyles long term.

People might continue to work from home, cycle rather than drive and swap international travel for more dreaded Zoom meetings.

If the world rapidly returns to ‘normal’, emissions will follow suit.

But if we choose otherwise, there’s a chance the fall in emissions will last longer than the time between birthdays.