Every winter, there’s up to a 30% chance that the common cold you have is a coronavirus. So why is this new strain changing the world?

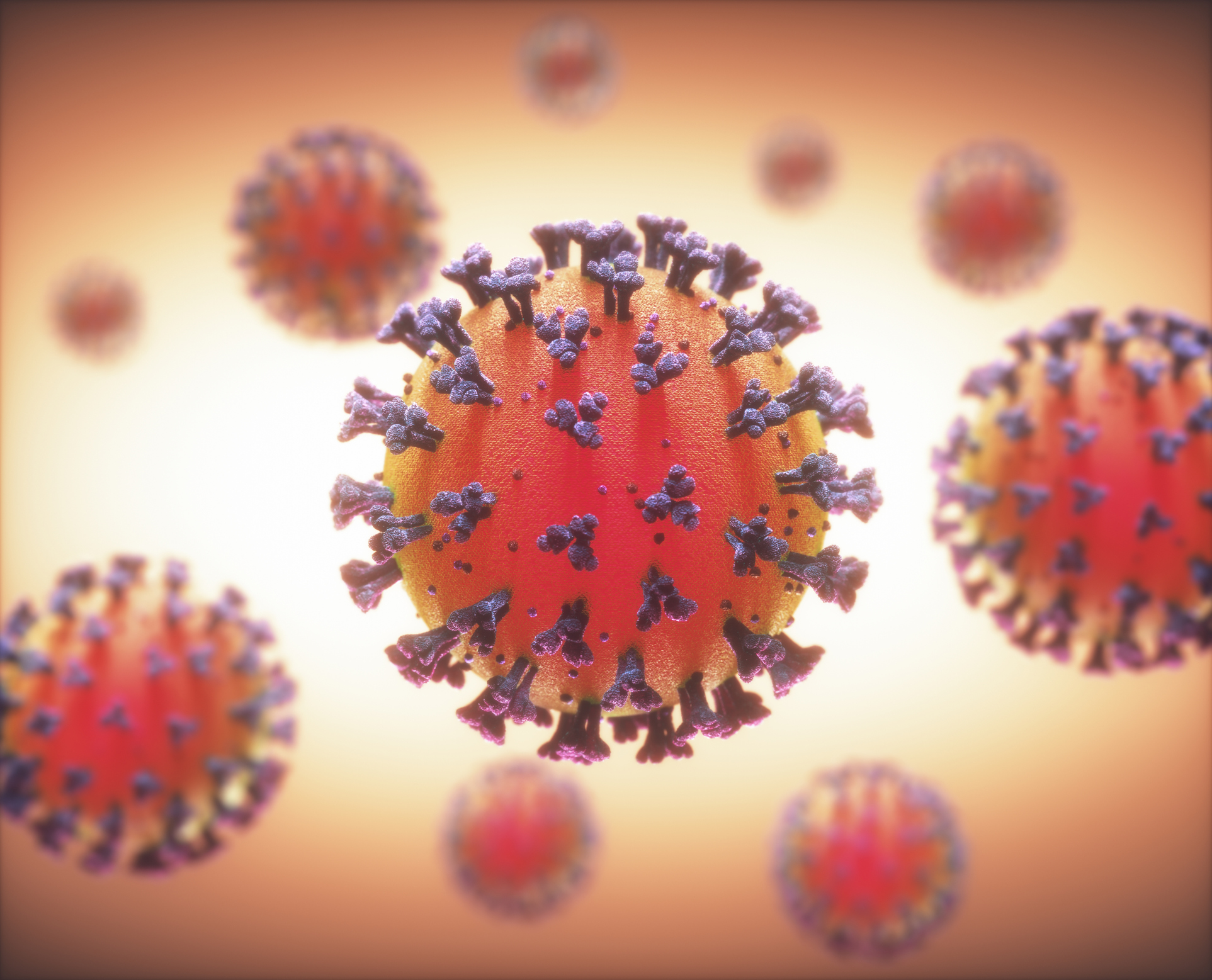

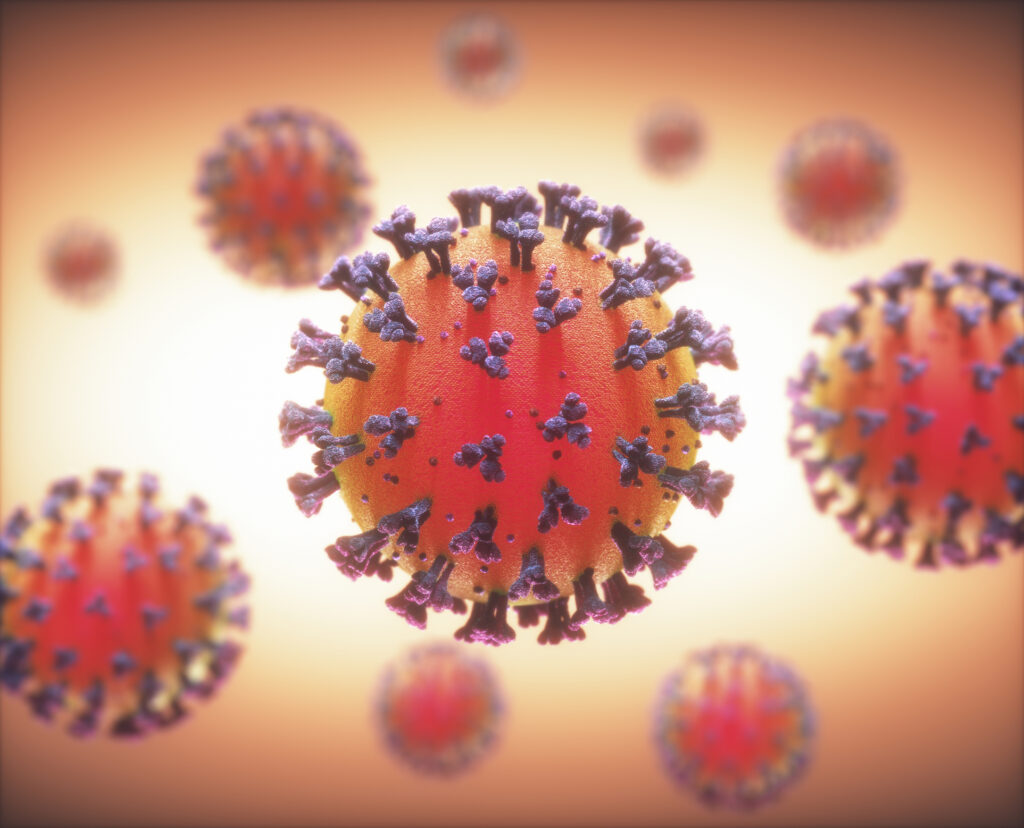

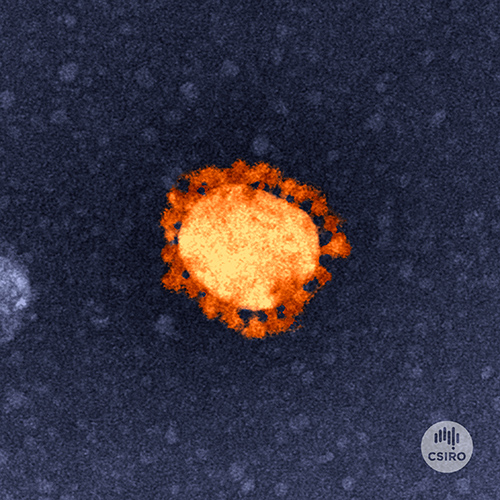

First, let’s get our terms down. A coronavirus is part of a group of viruses within the virus family Coronaviridae.

Coronaviruses include the strain responsible for the current global pandemic, the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) virus of 2003, the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS, also known as camel flu) of 2012 and some of our seasonal colds.

The proper name for the virus we’re all dealing with right now is SARS-CoV-2. If this virus infects you, you may develop an illness called COVID-19, which is much more fatal than the seasonal flu.

What we know

Researchers are still playing catch up to this deadly virus, but we do know some things.

Like others in its family, SARS-CoV-2 is a zoonotic virus – meaning it can spread from animals to humans.

By sequencing the virus’ genome and comparing it with its relatives, researchers found a similar coronavirus in bats.

But we still don’t know exactly how it was passed to humans.

What we do know is this new coronavirus is very good at what it does.

Viruses can’t reproduce on their own. Instead, they work their way into our cells and use them as factories to copy themselves.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus is shaped like a spiked ball. The spikes are a protein that attaches itself to an enzyme on the outer surface of the cells in our lungs called ACE2.

These spikes have evolved to strongly attach to ACE2 enzyme. This strong attachment makes the virus more infectious.

The virus uses its spike proteins to puncture the cell wall and release a genetic code that reprograms a cell to make more copies of the virus.

But that spike protein can also be used to make a vaccine.

Get your clamp on

Dr Keith Chappell is part of a partnership, between the University of Queensland and the Australian Institute of Bioengineering and Nanotechnology, that is trying to develop a vaccine for COVID-19.

“Years of experience and automated experiments allowed us to find a clamp to hold viruses,” says Keith.

“We clone a molecular clamp with the DNA sequence encoding of the spike protein.”

The clamp holds just the spike, without a virus attached, so our immune system can learn about it. That gives our bodies the chance to recognise the spike when it is on a virus – and kill it before it can spread.

The Fast and the Furin-ous

Normally, once the spike has punctured the cell wall, an enzyme that naturally occurs in our cells called furin cuts the spike from the virus particle, letting it infect the cell.

But when the team tried to use furin to cut their molecular clamp, it didn’t work. Instead, they are testing other enzymes to release the spike proteins.

“We need to change the furin cutting site for our clamp, so we had to screen changes to find another site,” says Keith.

Keith’s team developed their work assuming the next pandemic would come from influenza. But applying their work to this different family of viruses means rebuilding their molecular clamp for a heavier load.

“The biggest challenge with coronavirus spike proteins is their size. They’re two-and-a-half times larger than the spike proteins found on influenza [making them difficult to hold].”

Don’t stop washing just yet

While we need vaccines to stop the virus’ spread, they are still some time away.

Currently, the best thing to slow COVID-19 is still social isolation, hand washing – and listening to health experts.