When it comes to celebrating the achievements of scientists, there is a clear gender bias in Australian secondary classrooms.

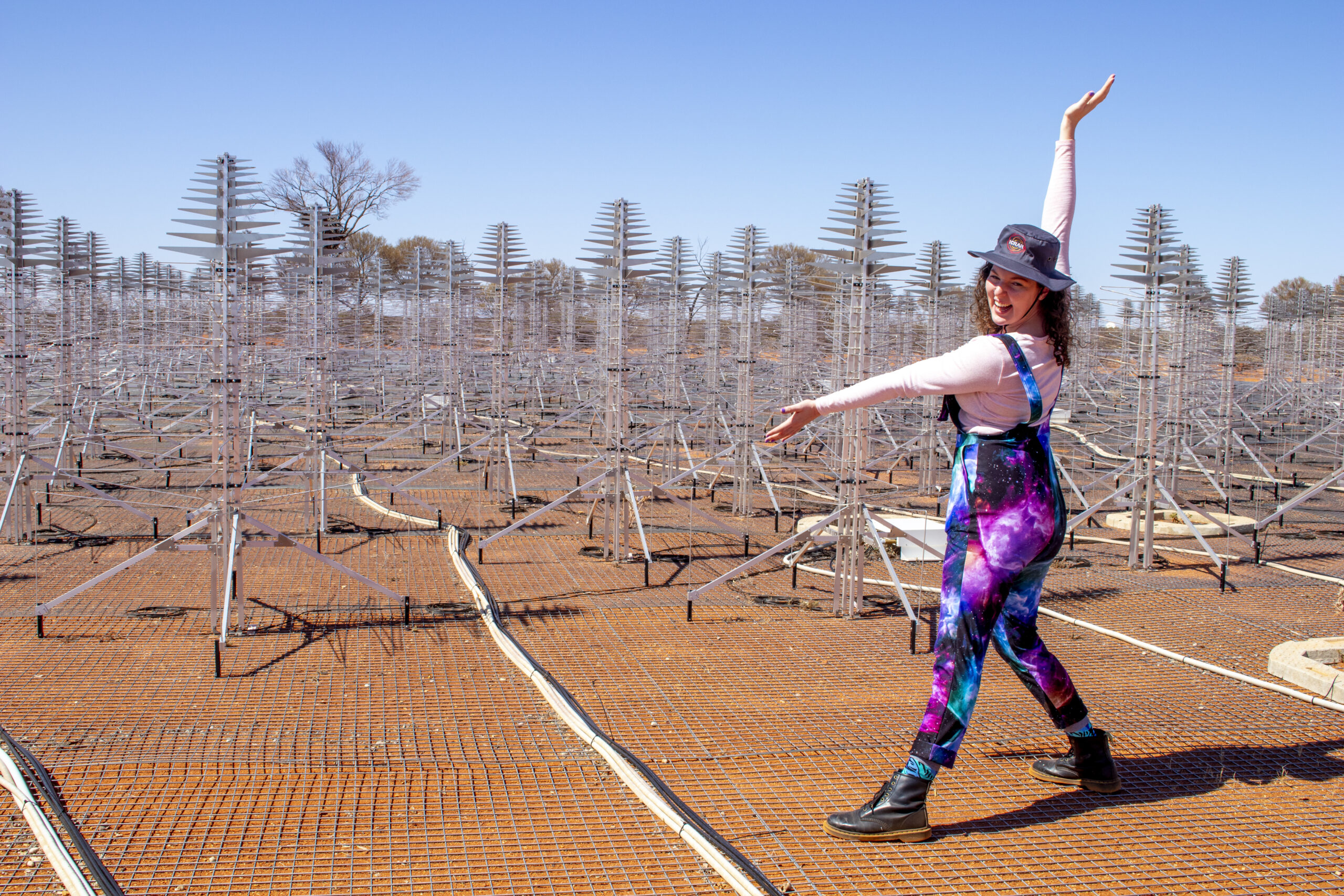

A recent study led by Dr Kat Ross, an astrophysicist at Curtin University, compared male and female representation in Year 11 and 12 biology, chemistry, physics and environmental science studies.

Of the 145 scientists mentioned within the syllabuses, only one was female.

DOIN’ IT FOR THEMSELVES

Kat was inspired to conduct the study while training physics teachers in an upcoming NSW syllabus.

“A colleague pointed out that, in the radioactivity section, Marie Curie wasn’t mentioned,” says Kat.

“That alone shocked me.”

“I figured if Marie Curie isn't mentioned, who else is missing?”

“I looked at the rest of the syllabus and saw no women mentioned.”

Kat realised this gender bias likely wasn’t limited to the physics curriculum in NSW.

STEM GENDER EQUITY

Women made up 37% of enrolments in Australian university STEM courses in 2022. And only 15% of STEM-qualified jobs were held by women.

While female participation in Year 12 STEM subjects increased from 45% to 47% between 2013 and 2021, the gender bias within the curriculum is of concern.

According to Kat, the senior years of high school can be a critical time for students making their career decisions.

Students may feel less inclined to pursue careers in maths, science, technology and engineering without visible role models.

“We’re essentially telling them, if you’re a woman and you’re interested in science, your career doesn’t go beyond high school,” says Kat.

So how do we tackle the problem of underrepresentation contributing to low engagement of women in scientific fields?

REPRESENTATION MATTERS

Relatable role models have major positive influences on young people across a variety of settings.

“People who can’t find role models can’t relate to people like them, have increased levels of imposter syndrome and lower levels of self-efficacy,” says Kat.

The lack of relatable role models also has “really damaging” effects on the self-confidence of young people.

“What we need is to have role models that students relate to. They have to be authentic.”

“[We need] multiple examples of role models at multiple stages of their career and education.”

LITTLE WOMEN

According to Kat, a combination of factors contribute to the lack of female representation in Australian science subjects.

“I think it wasn’t an active or intentional thing but more because people just weren’t aware,” says Kat.

“They weren’t making a conscious effort to include women.”

“But beyond that, it’s a cultural and systemic bias against women. And this undervaluing of the work that women do.”

Historically, male scientists have been credited for major discoveries. Methods or theories are named after a solo male figure, despite the work usually involving a large team.

“We’re fed this narrative of a lone male genius making these isolated discoveries by themselves,” says Kat.

“That’s not how science is done.”

FIGHTING TO #INCLUDEHER

Kat and a team of volunteers run the not-for-profit #IncludeHer campaign.

They work closely with curriculum developers – starting with the Queensland Curriculum and Assessment Authority – to implement changes to science education.

“We’re trying to get them to develop a science curriculum that’s far more inclusive and representative of what science is like in Australia,” says Kat.

“We’re hoping to work with other developers, including here in WA.”

“We’re also working with teachers to adapt their current lesson plans to include a broader representation of scientists.”

LACK OF DIVERSITY

It’s not just women who are underrepresented in Aussie classrooms – minority groups are too.

People who are culturally and linguistically diverse, gender diverse or have a disability are rarely mentioned.

The study found 75.9% of named scientists were European.

“There is not a single mention of an Australian scientist in the entire curriculum,” says Kat.

“Here in WA, we have had and continue to have some incredibly amazing scientists. We should be highlighting and celebrating that, but it’s not reflected in the curriculum.”

Note from editor: In this article, we have used binary notions of gender and gender identity (male and female) in line with how the main scientific study was written. However, Particle recognises and acknowledges diverse gender identities and the importance of inclusive language. As noted by Dr Kat Ross in her research paper, the invisibility of gender and culturally diverse scientists is an important problem that should be explored further in future research.