Evolution is usually considered like a sort of ancient mechanism that shaped the animals and plants we see today. A process that operated millions of years ago, leading to the formation of modern species. A slow process, in short, that happened aeons ago.

But evolution is far from a thing from the past.

Yes, it occurred millions of years ago, but it is still happening and you don’t need to look too far into our past to find evidence.

In humans, our brain was not always as big as we boast nowadays. Blue eyes are a common sight in many parts of the world, but 10,000, years ago they were unheard of. The human genome has been evolving too, with thousands of new genes being adopted over the past millennia.

It all boils down to natural selection and the question of whether a trait or characteristic is useful to improve your survival or mating success or if the trait is no longer needed. It’s like they say: use it or lose it!

Can you wiggle your ears?

I can. My wife and kids can’t move theirs. Can you?

Ear wiggling is possible by a group of muscles called auricularis, which are most prominently found in animals, like cats and dogs. These species can move their ears towards a sound source, like a potential prey. Humans cannot do that. Our ability to move our ears is quite limited, but it is there in some of us.

Another odd trait found in some of us is a little muscle found in your wrist, called palmaris longus. Just place your arm on a flat surface and move your thumb and pinky together. If you see a band raising within your skin, you have this muscle (it turns out I have that too). But no worries, the lack of this muscle has no effect on hand or grip, so those of you who lack it are just fine.

Ear wiggling and the palmaris longus are just a few of the evolutionary leftovers, more formally known as vestigial traits. A feature once present in our far ancestors that has been left behind. In evolutionary terms, this means that some people are born without this trait, and they do just fine. The trait is not harmful either, so people who are born with it may pass it along. That’s why the trait still remains. That’s evolution in action.

Vestigial traits are just one example of ongoing evolution. There are other good examples, like the shape of our brain.

Our evolving brain

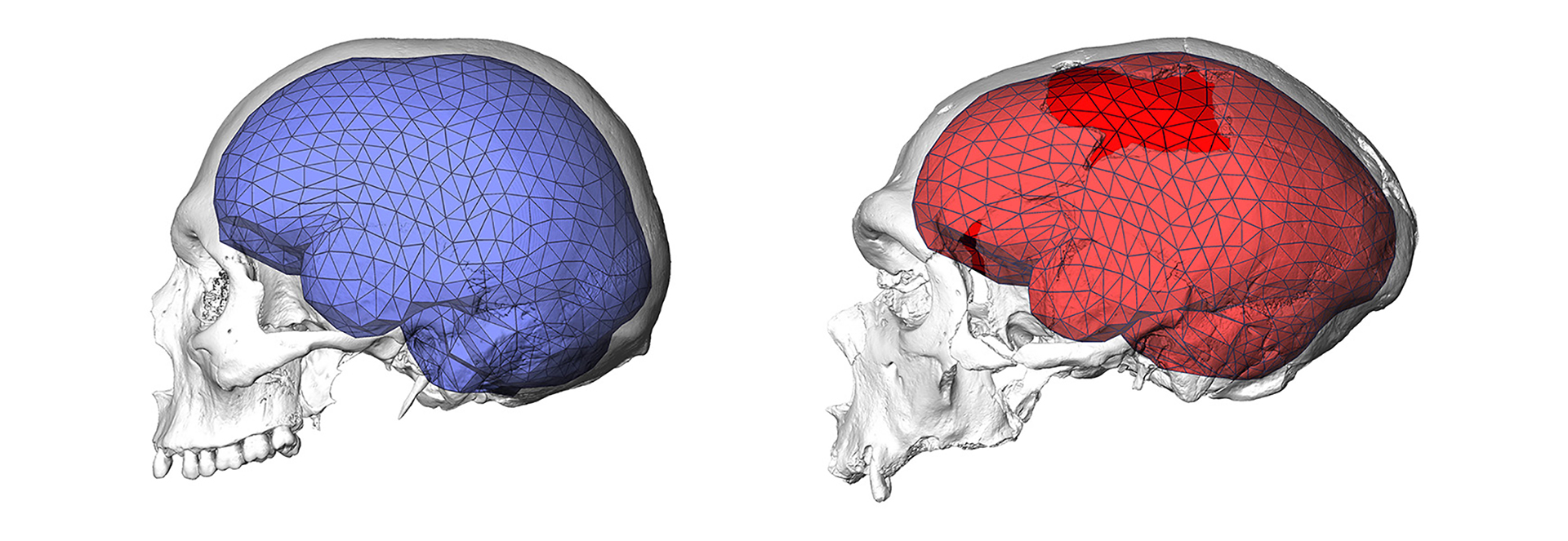

Officially, the oldest known humans roamed Earth about 315,000 years ago, according to a 2017 study. At this time, our brain was shaped differently, according to a recent study that created virtual imprints of the internal bony braincase of one of these ancient humans.

“The brain is responsible for the abilities that make us human, but early Homo sapiens about 300,000 years ago did not have brains like ours. Their brains had approximately the same size but were rather elongated like in our ancestors and like in Neanderthals and not globular like our brains today,” said Simon Neubauer from the Max-Planck-Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

“Only Homo sapiens fossils younger than 35,000 years show the same globular shape as present-day humans, suggesting that modern brain organisation evolved sometime between 100,000 and 35,000 years ago. We have been surprised to discover just how recent these changes to brain organisation were,” he added.

Brain size has also changed in the past 30,000 years, and several studies point to a reduction in size. One study estimated that the brain of modern humans has decreased in size from 1,500 to 1,359 cubic centimetres—that’s about the size of a cricket ball.

“I’d call that major downsizing in an evolutionary eye blink. This happened in China, Europe, Africa—everywhere we look,” said John Hawks from the University of Michigan in a 2011 news report.

A similar trend of brain reduction was found by another study that compared 175 braincases from humans and human relatives that lived 1.9 million to 10,000 years ago. A key finding of this study was a correlation between brain size and population density. “As complex societies emerged, the brain became smaller because people did not have to be as smart to stay alive,” said David Geary from the University of Missouri, who led the study, in a news report.

Brain aside, there are other features of our body that evolved quite recently. Look at your eyes, for example.

Blue eyes, brown eyes

All eyes are naturally brown. That’s because melanin, the pigment that gives our eyes and skin colour, is naturally brown. Eye colour is an optical illusion caused by decreasing amounts of melanin in your eyes.

For thousands of years, brown eyes were the rule. “Originally, we all had brown eyes,” said Professor Hans Eiberg from the Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine in a press release. “But a genetic mutation affecting the OCA2 gene in our chromosomes resulted in the creation of a ‘switch’, which literally turned off the ability to produce brown eyes,” he added.

Everyone around the world who has blue eyes got them from this evolutionary event, which occurred 6000 to 10,000 years ago, according to a study led by Hans.

“From this, we can conclude that all blue-eyed individuals are linked to the same ancestor. They have all inherited the same switch at exactly the same spot in their DNA.”

Even our height might be evolving. People in the Netherlands seem to be evolving upwards.

Increased height

According to a recent study, the Dutch have increased their height by 20 centimetres over the past 150 years.

The common thinking was that it had to do with improved lifestyle—things like rising wealth, a healthy diet and good healthcare systems. But this new study points to another reason: humans are still evolving.

“The main findings were that taller men had on average more children than shorter men in the Netherlands. These results are in contrast to findings in the US, where shorter women and average height men seem to have most children,” said Gert Stulp of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, who led the study.

The findings are a good example of human evolution in action. “Given the findings in the Netherlands, there is some support for the idea that the Dutch have become so tall not only because of environmental reasons (such as high-quality care, good nutrition, low inequality) but also because of natural selection favouring taller heights,” Gert said.

But Gert is quick to explain that, while there is an observable evolutionary role, environmental factors are likely to play an important role too.

“This study drives home the message that the human population is still subject to natural selection,” said Stephen Stearns, an evolutionary biologist at Yale University in a recent news report. “It strikes at the core of our understanding of human nature and how malleable it is.”

These are all just a few examples of recent human evolution, but others are around. Like our ability to digest milk, which evolved just a few thousand years ago, or our inability to produce vitamin C, which is due to a mutation that occurred long ago. So, just wonder, how will we evolve in a few thousand years?