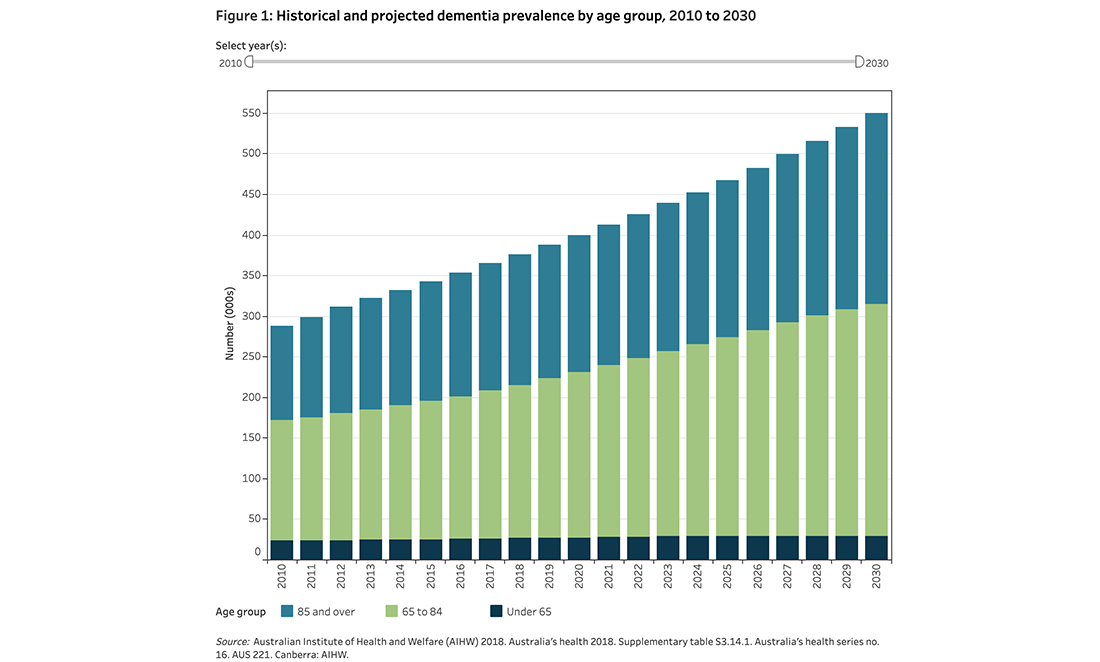

Dementia is the second leading cause of death of Australians and the leading cause of death for women, according to Dementia Australia.

Of around 472,000 Australians with dementia, Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form. It makes up to 70% of diagnosed cases.

In WA, more than 41,500 people live with Alzheimer’s, a figure projected to exceed 84,000 by 2036 without a medical breakthrough.

Now, groundbreaking WA-led research has identified the likely cause of this debilitating disease.

A century-old clue

The first case of Alzheimer’s was diagnosed over 100 years ago by Dr Alois Alzheimer. German 51-year-old seamstress Auguste Deter puzzled her hospital carers after being admitted with memory impairment, mania, insomnia and agitation.

Her polite manner seemed to change each evening. As her condition worsened, Auguste forgot her name, how to speak and eventually couldn’t eat.

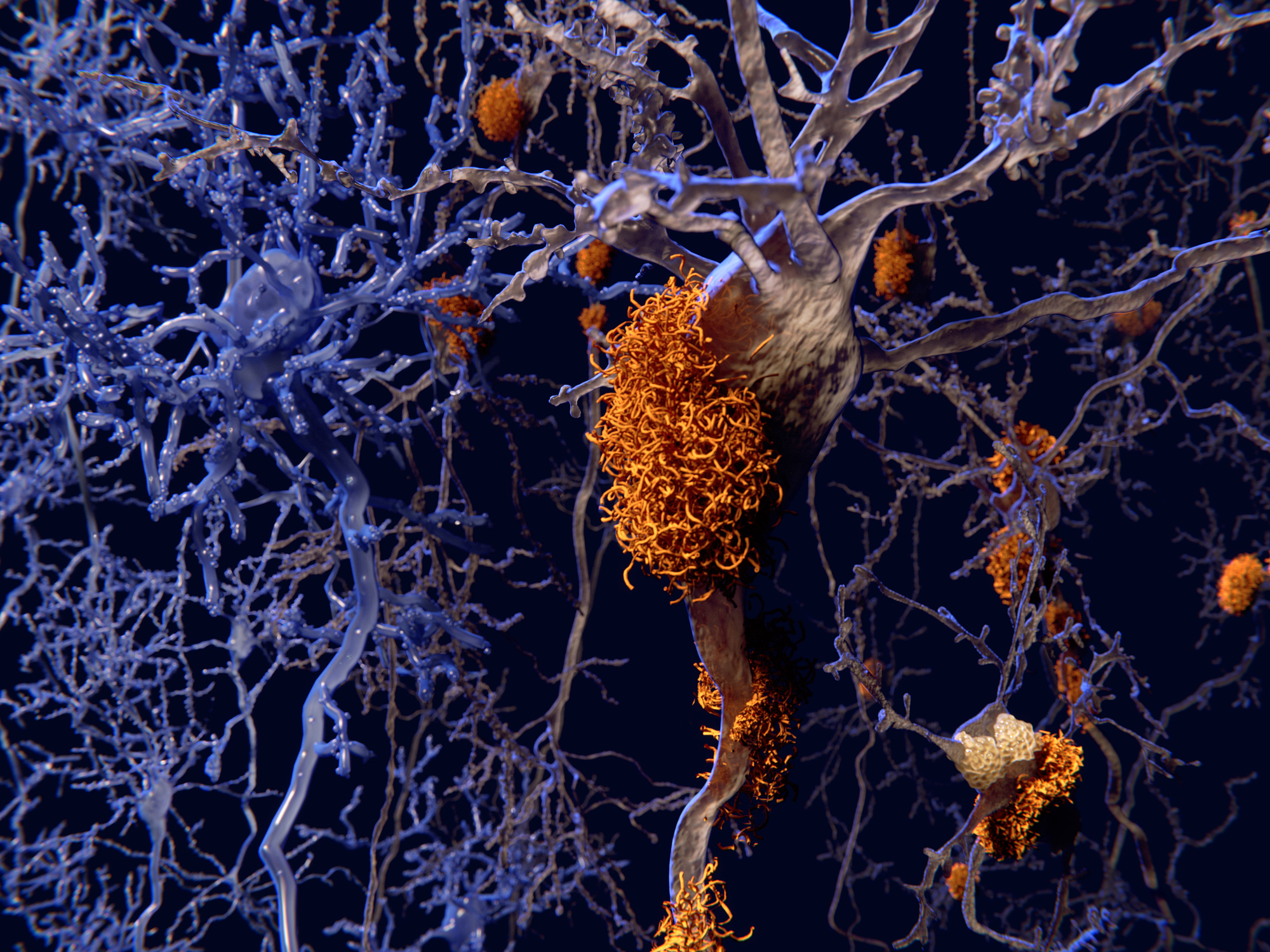

After she died, Dr Alzheimer biopsied Auguste’s brain. He found the area that controls memory, language and judgement – the cerebral cortex – had thinned. Plaque had formed around neurons, and her nerve fibres were tangled.

While the cause of Alzheimer’s has continued to perplex medical experts for the past century, the plaque on Auguste’s brain held a vital clue.

Bypassing the brain’s ‘bouncers’

The human brain is a well-protected organ. The skull shields it from external damage, while a blood-brain barrier protects it from internal contamination.

Macrophage immune cells patrol the corridors of the central nervous system, while endothelial cells act like bricks in a wall around the brain.

Nutrient and efflux transporter cells work like the brain’s bouncers. They sort valuable molecules, like oxygen and glucose, from the riff-raff that could play havoc with your neurons.

Then 25 square metres of blood vessels deliver the nutrients throughout the brain. With Alzheimer’s, it seems like something’s bypassing the bouncers to get inside.

A new ‘blood-to-brain pathway’

The plaque found in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients forms a toxic protein called beta-amyloid. Japanese and Australian scientists previously identified that 90% of beta-amyloid is found in blood plasma cells.

This was the start of research that led Professor John Mamo and his team at Curtin University to identify that low-density lipoproteins (LDL) were the cause.

You may have heard of LDL if you have had a cholesterol test. Processed fatty foods contain LDL cholesterol, which is associated with heart disease. It turns out that LDL also acts like a delivery service for beta-amyloid to build up in the brain.

“A lipoprotein [like LDL] reflects tiny spherical globules of fat,” says John, “and the lipoprotein structure allows you to transport fats, which normally aren’t soluble in an aqueous environment.”

Until now, how beta-amyloid accumulated in the brain of Alzheimer’s patients was unknown. Their study identified a new ‘blood-to-brain pathway’.

‘Blind mice’ breakthrough

Let’s break down how it works. Foods high in saturated fatty acids increase the production of beta-amyloid in the small intestine. Cells use amyloid to break down lipid proteins for energy. But fatty acids ramp up amyloid production. This means more toxic beta-amyloid, which ends up in your brain.

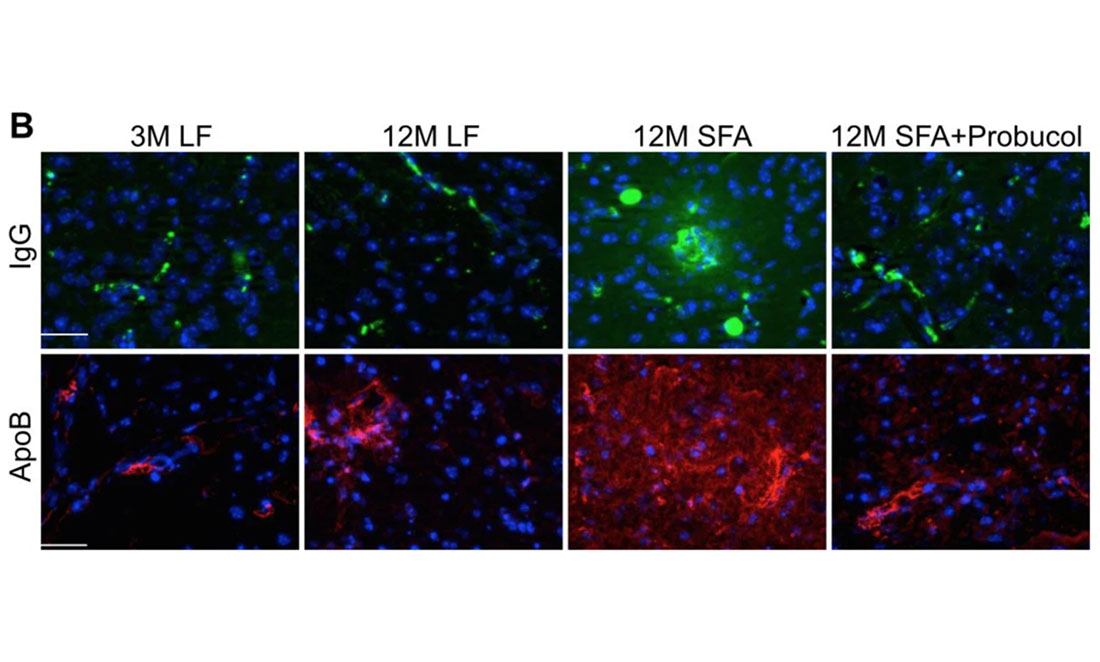

To test this, John compared mice genetically modified to produce beta-amyloid in their liver. His team mixed these animals with unmodified mice. They then performed blind tests on all the mice, which meant they didn’t know which mice were modified until the end.

John tested how quickly the mice could learn, then scanned their brains to see the build-up of beta-amyloid. Unexpectedly, the modified mice began mental decline before the scans showed significant plaque.

“At 18 months of age – that’s kind of like 70 for humans – you rarely see any hardcore plaque,” John says. “The disturbance is occurring and brain cells are dying off well before you got the hardcore plaque.”

This is significant because brain imaging is one way doctors diagnose Alzheimer’s. If the damage is occurring before plaque accumulates, it makes it harder to differentiate from other forms of dementia. Inflammation and brain cell death may be happening before beta-amyloid builds up to visible levels.

So what does this mean for future prevention and treatment?

A probucol protocol

John began treating the mice with a well-known drug, probucol, originally designed to treat heart disease. Unlike other heart disease drugs, it works by reducing the amount of LDLs in the blood.

Probucol was replaced by cholesterol-lowering drugs called statins in the late 80s for a few reasons. Along with the “bad” cholesterol LDLs, it reduced “good” high-density lipoproteins in blood. Secondly, some test animals had elongated QT intervals, which meant electricity took longer to pass through the heart’s muscle tissue. In extreme cases, this led to the animal’s death. Thirdly, the drug company’s patent was ending.

In recent years, researchers have considered probucol for a number of lipoprotein treatments. This motivated John to test it for the treatment of Alzheimer’s.

Probucol has a few things working for it. It’s hydrophobic like beta-amyloid, so it tends to get packaged by lipoproteins and sent to the brain too. This means it can pass the blood-brain barrier and treat beta-amyloid contamination in the brain directly.

Slowing memory loss

John found probucol strengthened the brain capillaries that were leaking because of higher fatty acid levels. It made the protective wall around the brain stronger. As a powerful antioxidant, it can also prevent cells from releasing toxins due to inflammation stress.

John says it stops beta-amyloid penetrating the brain.

“And even if some gets in there, the drug is anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative. That’s pretty handy to have,” says John. Plus it’s cheap.

It’s early days, but John is about to conduct clinical trials to see if probucol can work on humans.

It’s not a miracle cure. The blood-brain barrier degrades with age whether you have lots of beta-amyloid or not.

But for those with a genetic or environmental risk of plaque build-up, probucol could slow the progression of Alzheimer’s for years. With most people getting Alzheimer’s in their 70s and 80s, it could offer a big boost for their quality of life.