“I was two when I was taken,” says Noongar Goreng man Timothy Flowers. “It was night-time.”

Timothy is a survivor of the Stolen Generations. During this time, more than 17,000 children were forcibly removed from their families by the Australian Government.

In 2008, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd apologised to the Stolen Generations as part of the National Apology to Australia’s Indigenous Peoples.

Known as the ‘Sorry’ speech, it’s considered a defining moment in Australian history.

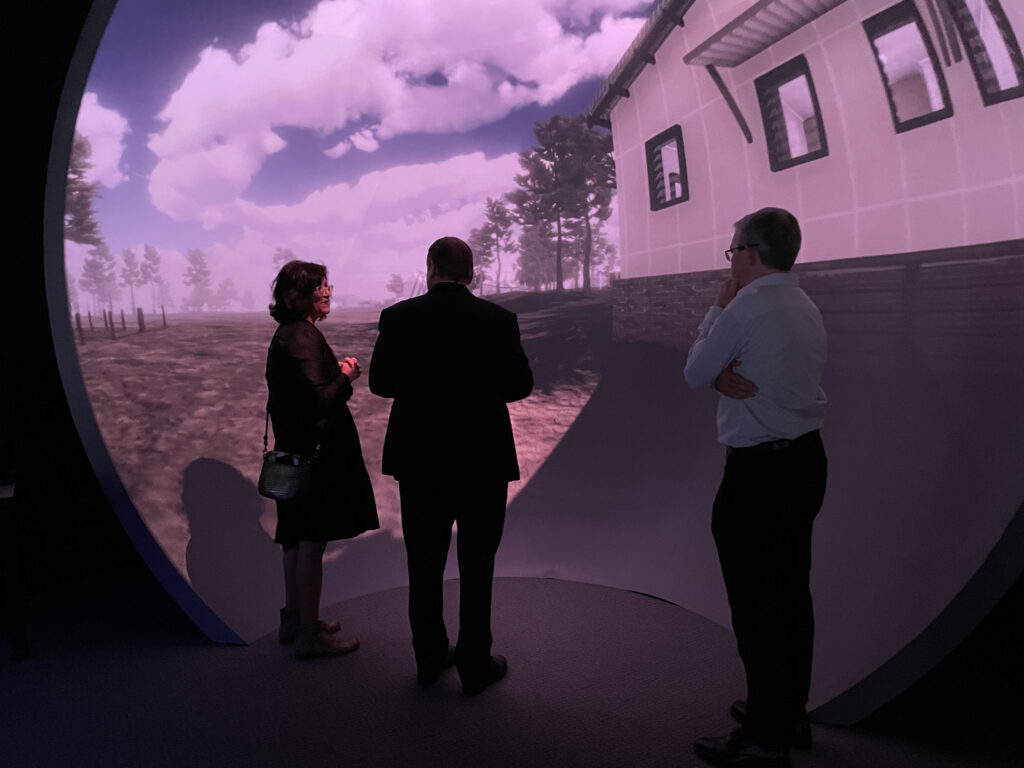

Now, virtual reality (VR) is being used to continue healing and reconciliation.

HOW CAN VR HELP?

Missions Connect is a multi-award-winning Curtin University research study that aims to educate the community about the Stolen Generations using VR.

The project is run by Professor Reena Tiwari and Jim Morrison.

Jim’s a Minang-Goreng Noongar elder and Chairman of the WA Aboriginal Stolen Generation Corporation.

Using VR means survivors don’t have to go on Country, where sites are “bang smack in the middle of nowhere”, says Timothy.

Instead, survivors can talk to their families about what happened to them in the comfort of their community.

A REVELATION

“The whole thing came about accidentally,” says Reena.

Mission sites weren’t being restored, so Reena and her team started digital documentation of the sites.

And Stolen Generations survivors were invited to view the virtual sites.

According to Reena, it was a revelation for everyone.

MISSION POSSIBLE

The team used lasers, drones and cameras to recreate the missions virtually.

They reconstructed the sites in 3D and edited them based on archival documents and survivors’ recollections.

Timothy contributed his memory of the Marribank Mission, near Katanning, where he was taken.

Marribank is on the border of three shires: Woodanilling, Katanning and Kojonup. None of which took specific responsibility of Marribank.

“We told them how many beds were in a room or where the table was in the kitchen,” says Timothy.

“I could help them get it as close to reality as it could be.”

Reena says that, without survivors’ contributions, “Missions Connect would have been Mission Impossible.”

The first virtual environment was completed in 2019.

“VR is more than just a cool, hyped-up technology,” says Reena.

“It’s a whole new way to communicate about the Stolen Generations.”

“It connected people to people and people to places.”

COLLECTIVE HEALING

Jim’s parents and grandparents were survivors of the Stolen Generations.

He says VR provides the wider community “a bit more of a reality of what happened to Aboriginal children”.

The project has been able to bring back ‘collective healing‘ – a model where people with similar experiences share their stories to heal themselves, their families and their communities.

It’s powerful because many First Nations people are uncomfortable with Western therapy systems because they are not culturally safe.

Timothy says people living in Katanning weren’t aware of the Marribank Mission, despite it being only 20km away.

Thanks to the Missions Connect project, “more and more stolen people are telling their stories and being confident about telling their stories,” says Jim.

A PAINFUL PAST

In addition to virtual environments, Missions Connect has also created educational tools.

The first tool is professional development sessions with teachers. These sessions are also being used to raise cultural awareness in corporate and government organisations.

Next, they would like to incorporate Stolen Generations into the Australian Curriculum.

Currently, Australian schools aren’t teaching about massacres, stolen wages or Stolen Generations. As a result, it’s not uncommon for school children to be unaware of the gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

“Some Aboriginal children didn’t know what a mummy or a daddy was,” Jim says.

“These things are hurtful but have to be addressed.”

VIRTUAL THERAPY

Missions Connect is also working with an Aboriginal psychologist to understand its importance for survivors of the Stolen Generations.

“Virtual reality has a place as a therapeutic tool,” says Jim.

For Timothy, Missions Connect has enabled him to share his story and work on his healing process.

“For many years, the history of the Stolen Generations was swept under the carpet,” says Timothy.

“All of this history in us we can now share with the wider community.”

GOING GLOBAL

So far, six mission sites have been recreated in virtual environments.

Missions Connect is now working with Indigenous people to create virtual reality of mission sites located in the eastern states.

Reena and Jim have travelled to Canada to establish a similar program with the University of Calgary.

“The future for us is to collaborate with global First Nations communities,” says Reena.

A TIME FOR RECONCILIATION

Missions Connect is addressing one of Australia’s most pressing national priorities: reconciliation.

“Missions Connect has been able to provide the oldest living culture in the world with the newest technology,” says Reena.

“We need to have the capacity for truth-telling from Aboriginal eyes. And for non-Aboriginal eyes to understand it and appreciate it.” says Jim.

For Timothy, this project has been the next big step towards reconciliation since the National Apology.

After the Stolen Generations, Timothy said he had to walk alone. Now, with Mission Connect, everyone can “walk together, side by side.”