On 2 January 2024, Sholto David dropped a blog post on the website For Better Science that would send ripples through a major American research institute.

In dozens of cancer research papers, he found unusual duplicated imagery. The papers were authored by researchers from the famous Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, a world leader in cancer treatments and research based in Boston, USA.

Sholto, who received his PhD in cellular molecular biology in 2019 from Newcastle University in the UK, spent much of his day investigating papers like this for free.

Eventually, his sleuthing helped to inspire a dramatic course of action. By the end of January, Dana-Farber said it would be retracting six of the papers – essentially, striking the results from the scientific record – and correcting 31 others. This work saw Sholto celebrated as a member of the TIME 100 Next list in 2024.

Credit: Francesca Jones/The Guardian

“Sholto David has made it his mission to shine light on shoddy scientific studies like some sort of superhero – albeit without the spandex costume,” reads his entry.

Discovering shoddy science has become much more prominent over the past decade, in many cases driven by ragtag groups of independent researchers. Some of them studied science, like Sholto. Others come from different walks of life.

The media has dubbed them the ‘science sleuths’ – regular folk interested in maintaining the integrity of the scientific record.

And though no spandex is involved, they’ve sometimes come together like a Science Avengers to explore the scientific literature, examining images and data for inconsistencies, accidental or otherwise, and flagging problems in highly regarded, peer-reviewed research.

What’s a science sleuth?

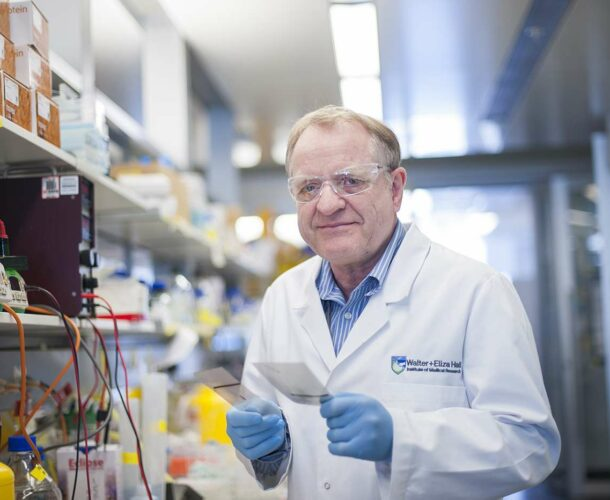

Simply put, a sleuth is “someone who examines research publications for evidence of possible research misconduct and reports it,” says David Vaux, an Australian research integrity specialist and Emeritus Professor at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute in Melbourne.

This is not work that is paid for by scientific organisations or research institutes. Many sleuths interrogate scientific papers in their spare time.

“They are hobbyists, do-gooders, idealists,” says Csaba Szabo, a professor at the University of Fribourg, Switzerland. “There is no reward (financial or even much in terms of recognition), and this is not a paid job or even a career.”

Sholto’s exploits have seen him gain recognition in recent years, but perhaps the most famous example of a science sleuth is Elisabeth Bik, a Dutch microbiologist with an almost supernatural ability to find duplicated images in scientific papers.

Her work has resulted in splashy stories in The New Yorker and profiles in many other magazines. She’s left thousands of comments on the website PubPeer, which allows anyone to leave comments about potential problems they find in published research papers.

“PubPeer empowers whistle-blowers,” says David. “It allows concerns based on evidence to be publicly reported, while preventing retribution.”

Credit: via WEHI

It was on PubPeer where Sholto left many comments – under a pseudonym – about the inconsistencies in papers from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. In one paper, he noted images of mice, laid flat on their backs, had been used twice to represent different experiments. A big no-no.

Sholto was able to detect some errors with the help of an AI program known as ImageTwin, which is capable of spotting image duplications across a wide variety of papers.

Elisabeth, who has had a hand in getting more than 1300 scientific papers retracted, can spot these duplications mostly with eyesight alone.

But no matter the method the work these sleuths do – trying to catch cons as if they’re a cross between Wonder Woman, Sherlock Holmes and Einstein – is exceptionally difficult.

Not just because it can be very hard to spot errors in scientific papers but because there’s no money in it, you can’t make a career out of it and it can be alienating.

“It is hard because they do it part-time, in their free time, typically alone and without any institutional or infrastructural support,” says Csaba.

Accusations of scientific misconduct often attract big legal risks too. In pointing out flawed research, sleuths open themselves up to retaliatory attacks or defamation cases.

Why, with such disincentives, would anyone want to do it?

An important job

Csaba says that society should be happy that sleuths are exposing some of the shoddy science that gets published – but not too happy.

“The fact that sleuths exist highlights the fact that nobody in the professional scientific ecosystem (not the granting agencies, not the health ministries, not the university administrators, not the department chairs and definitely not the journals) does this type of work,” he says.

In the current landscape, sleuths are filling an important gap, but Csaba and others are concerned that this work is falling to a ragtag group of hobbyists rather than institutions.

Credit: Carsten Koall/Getty Images

That’s not to say some of these places aren’t trying to prevent research misconduct.

Journals and publishers are taking steps to prevent shoddy research from being published in the first place.

Springer Nature, one of the biggest scientific publishers in the world, recently rolled out its own AI tool that scours a paper’s references and flags potential problems for a human editor to manually assess. And funding bodies, like the Australian Research Council, have codes of conduct that must be adhered to if researchers hope to be awarded lucrative grants.

Still, bad science slips through. It’s after papers are published where the system seems to be falling down, leaving critical work to the sleuths.

And there are concerns it could get much harder to sleuth in the near future.

Generative artificial intelligence platforms such as ChatGPT and image generators like Midjourney or DALL-E present an even greater challenge for research integrity.

Sleuths have been particularly adept at unearthing problems in older research papers, stretching back decades. But with new AI tools, bad actors can generate entirely convincing fakes of X-ray imagery, cells under a microscope and pictures of tumours. Even the underlying data can be faked.

It sounds hopeless almost. But research fraud and misconduct remains a small slice of the scientific enterprise. And for the bad actors who try to take advantage of the system, there are the sleuths.

There is room for optimism then.

“If there is fraud in papers being published right now which we are not catching, there will be people much smarter than me who are currently studying, and they will be ready to tackle this problem in the future!” says Sholto.