If you’ve ever been admitted to hospital, you’ve probably had it.

Cannulation – inserting a drip to draw blood or deliver medication – is one of the most common procedures in Australian hospitals.

But the first attempt at cannulation fails about 40% of the time. For children and chemotherapy patients, the failure rate is up to 70%.

It’s a problem biomedical engineer and UWA PhD candidate Nikhilesh Bappoo aims to solve.

FIRST TIME, EVERY TIME

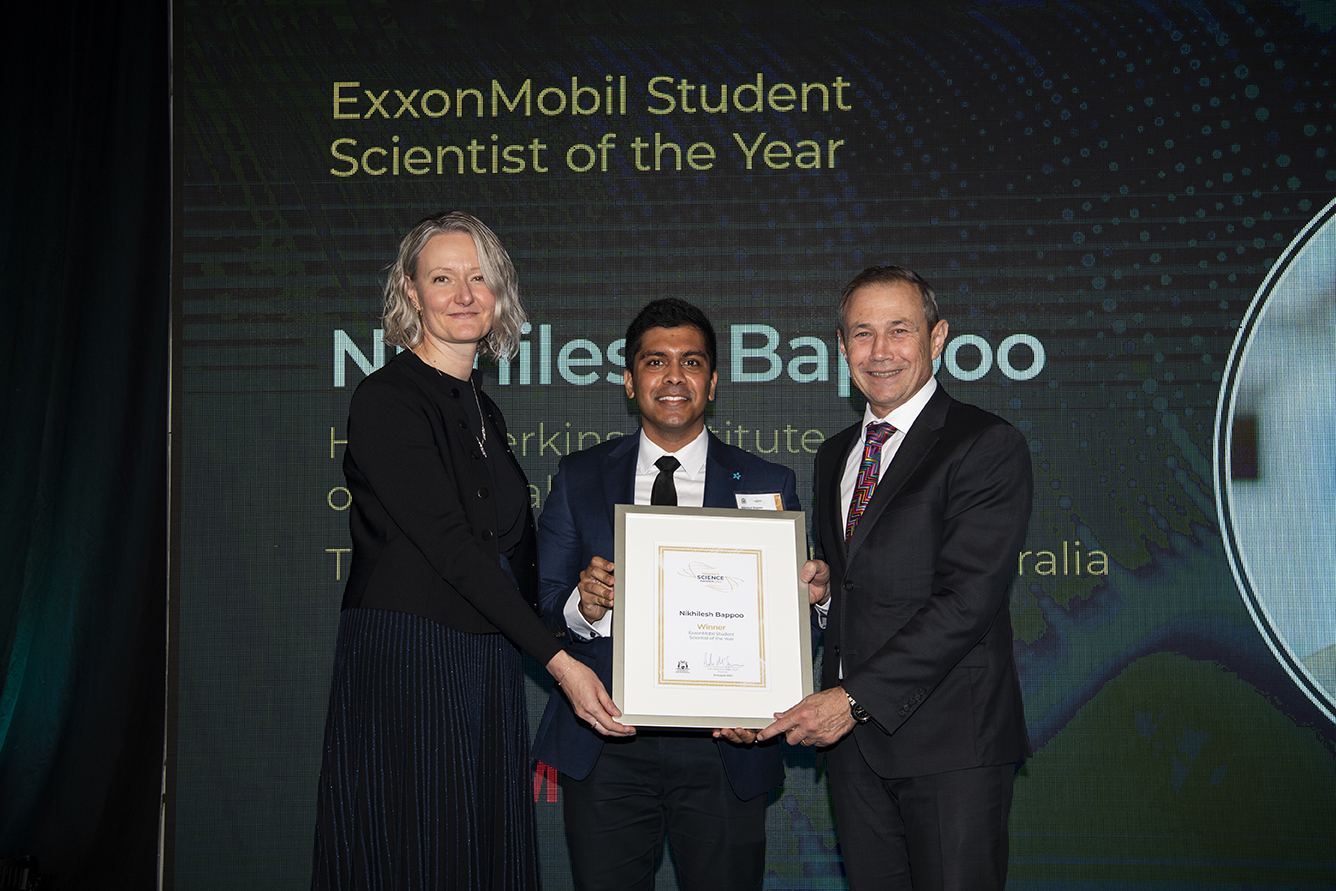

Nik, who was recently named WA’s Student Scientist of the Year at the Premier’s Science Awards, is an expert in how blood flows through the body.

Nik Bappoo

He’s also the co-founder and chief technology officer of VeinTech, a startup that aims to help clinicians hit the vein first time, every time.

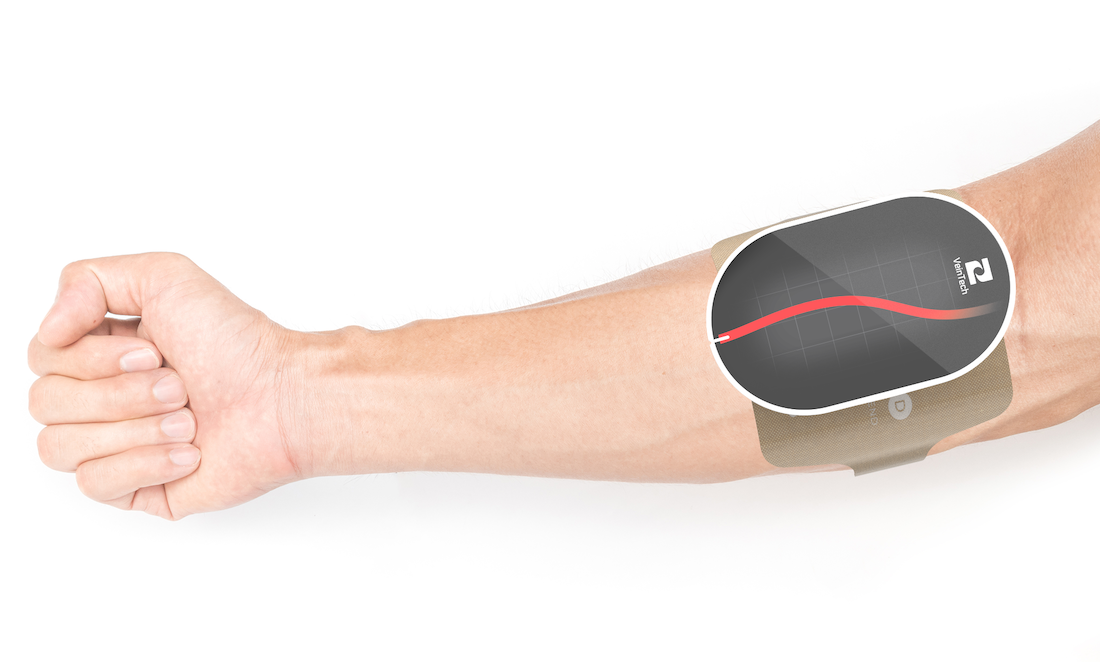

The company has developed a mobile phone-sized device that doctors and nurses place against a patient’s arm to find the vein.

“It’s an ultrasound-based technology,” says Nik, “so it continuously emits sound waves and receives those sound waves back.

“We’ve developed some [artificial intelligence tools] to process those signals … and then display those signals in a way that’s understandable by anyone.”

Nik says the design removes the complexity and training requirement of standard ultrasound machines.

“[We’ve] made it ‘ultrasound for dummies’ in a way,” he says. “I could pick it up and find a vein.”

FROM THE LAB TO THE CLINIC

Growing up on the island of Mauritius, Nik saw firsthand how a lack of access to healthcare, technology and education impacted his loved ones.

After moving to Australia, Nik still saw unmet clinical needs and barriers to access, particularly while volunteering in rural WA.

These observations have driven him to use his passion for science, engineering and medicine to reduce those inequalities.

Much of Nik’s research has been simulating blood flow in the placenta and understanding causes of aneurysms.

He was previously involved in VitalTrace, a WA company developing new fetal monitoring technology.

Nik admits moving from pure research to commercialising tech has been a steep learning curve. But his scientific mindset has proven useful in business.

“The integrity and the rigour you have to have as a scientist is exactly the same when you’re running a business and trying to raise investment or apply for grants to fund your work,” says Nik.

“A lot of assumptions that you have in business – like is your customer going to buy this product for X price – you validate them very scientifically.”

UNDERSTANDING THE WHY

Nik’s found it useful to have mentors in world-leading medical researchers who turned their ideas into products.

His advice for young researchers looking to commercialise their ideas is to spend 80–90% of their time trying to truly understand the problem they hope to solve.

“The traditional way of doing research is you just go and do something based on what the literature might suggest or what your interests are,” says Nik.

“And then you try to retrospectively fit it to a real-world application.

“My personal philosophy is starting with a need … and then using that as the launching pad to do the research.”

Nik believes understanding why you want to do the research is the most powerful tool.

“Where does that passion come from? Why do you want to make this impact in this field?” asks Nik.

“Having that crystal clear from the get-go is probably one of the most useful things I’ve done.

“Because research and commercialisation – it’s tough. And knowing why you’re doing what you’re doing is quite useful when things get hard.”