The Hon Murray Watt recently approved the extension of the Scarborough Gas Pipeline.

Before its new closure date in 2070, it’s going to contribute an estimated 4.3 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide to the Earth’s atmosphere.

For Watt’s first job as Australia’s Minister for the Environment and Water, it seems an odd choice.

So whose responsibility is it to protect Australia’s environment – and are we any good at it?

REFLECTING ON THE ROLE

The Australian Government introduced an environment minister in 1971. Since then, there have been 34 ministers and 21 name changes.

These titles have ranged from the simple Minister of the Environment to the seemingly overworked Minister for Arts, Sport, the Environment, Tourism and Territories.

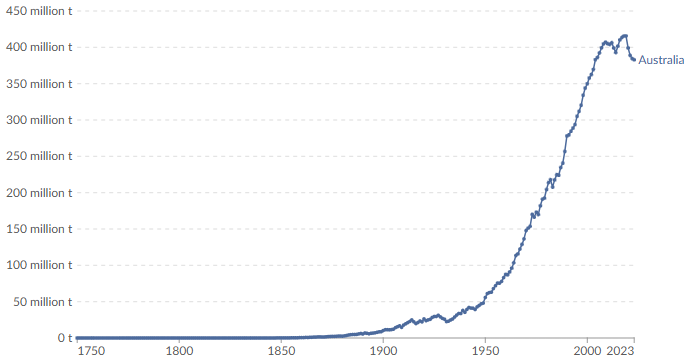

Yet since the introduction of the environment minister, 23 species have become extinct (or are currently expected to be), Australia’s carbon dioxide emissions have doubled and our average land and ocean temperatures continue to increase.

Credit: OurWorldinData (CC BY)

The similarity between all of the environment ministers and their governments appears to be that they are not fulfilling their responsibility to protect and conserve Australia’s environment.

TAKING THE LEAD

Dr Justin Alger is a senior lecturer in political science at the University of Melbourne.

In terms of responsibility for the environment, Justin says, “At the end of the day, the government has really gotta take the lead on this.

“Australia’s conservation laws … actually allow for a considerable amount of flexibility in how protected areas are managed.

“The sitting environment minister tends to have a lot more influence over the processes around and the implementation of management plans for protected spaces.”

These protected spaces include national parks or Marine Protected Areas.

A BALANCING ACT

Being the environment minister isn’t an easy job. They must balance the environmental and economic needs of the country.

In an interview with The Saturday Paper, Watt describes the role as “a guardian of Australia’s natural environment”.

When Labor came into power in 2022, they promised overhauls of Australia’s environmental laws and a reverse in the decline of Australia’s 110 ‘priority’ species and 20 places.

The Environment Minister at the time Tanya Plibersek said, “I will not shy away from difficult problems or accept environmental decline and extinction as inevitable.”

Credit: Mick Tsikas/AAP Image

Instead, Plibersek approved a new coal mine and the extension of three others, didn’t reverse the 110 priority species and failed to produce environmental law reform.

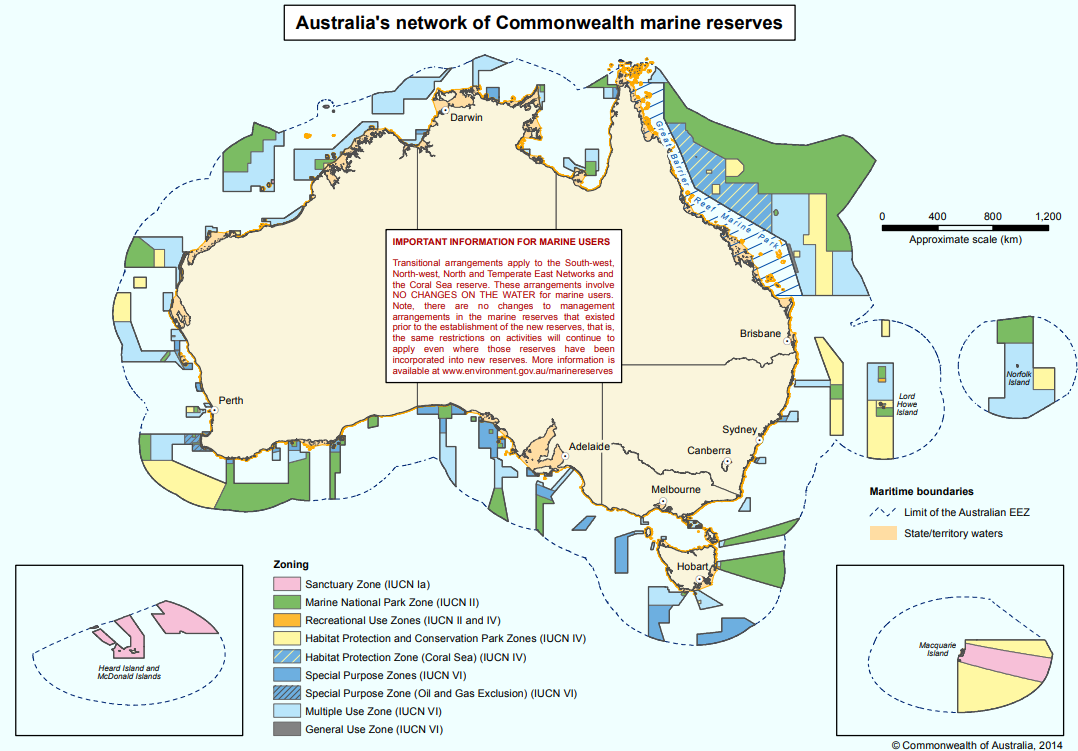

Plibersek and the 32 environment ministers before her have often opted for addressing Australia’s environmental problems by expanding or creating national parks, marine parks or World Heritage listed areas.

It appears Watt’s tactics will be no different.

RESERVED RESERVES

After approving the extension of the Scarborough Gas Pipeline, Watt announced that Australia would create more marine reserves.

Justin thinks this is a worthy strategy.

“Setting aside large tracks of nature – ocean and terrestrial – is important for ensuring its longevity,” says Justin.

Australia has one of the highest percentages of marine reserves. However, marine reserves don’t fix the climate crisis, and they fail to protect areas of the ocean with large natural gas fields.

“It’s not just about creating an area with some splashy title,” says Justin.

“It’s about following through on them and making sure they’re actually protected. Not just in name, but in practice.”

Credit: © Commonwealth of Australia via DCCEEW

IT’S JUST NOT WORKING

Australia has historically been a leader in conservation, having established the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park in 1975.

But Justin says many of Australia’s marine parks are classified as ‘mixed use’ so all stakeholders can benefit, whether it’s a commercial fishery, an oil and gas company or a dive tour boat.

“It’s kind of how Australia has managed most of its marine protected areas for decades. It’s just not working,” says Justin.

“Any time these stakeholder battles emerge around a specific space … the default is always to go back to that framework of how we can make it work for everybody?

“The reality is that doesn’t necessarily work out well for the environment.”

CLEARLY BAD FOR THE ENVIRONMENT

After the downfalls of previous environment ministers to protect and conserve Aussie animals and landscapes, ‘the fixer’ stepped in.

Unfortunately, Watt hasn’t fixed it. He approved the Scarborough Gas Pipeline extension.

“It is endemic of how the federal government in Australia has tended to manage marine spaces for decades,” says Justin.

“It’s likely that the environment minister knows on some level that this is not sustainable, that this is not working towards environmental objectives.

“Because it’s clearly bad for the environment.

“There’s ample evidence of ecosystem decline as a result of nearby commercial activities.

“It requires a shift in mindset, including of how the federal government thinks about these trade-offs. So far, these trade-offs are focused on keeping people in business.”

Credit: Woodside

OVERESTIMATING OURSELVES

So how does Australia rate for environmental conservation?

“Probably slightly below average,” says Justin.

“Australia is falling behind because of this mixed-use approach to protected space.

“It’s tragic. Iconic biodiversity hotspots in this country are degrading really rapidly – partly because of mismanagement, partly because of climate change, which is beyond Australia’s capacity to solve alone.”

Justin says a mindset change is necessary.

“We need to change the mindset of how we conserve things and recognising that we need to prioritise it more than we do,” says Justin.

“Because we aren’t prioritising it as much as we think we are.”