If you go to the emergency department with a bacterial infection, it takes up to five days to find out what’s making you sick and how to treat it.

That’s because pathologists have to grow the bacteria in liquid or on special plates before they can test which antibiotics are effective.

If you have sepsis, or blood poisoning, you’re at risk of dying before your doctor even receives the results.

“If you aren’t receiving an appropriate antibiotic, every hour without it is a 6.7% risk of death,” says microbiologist Dr Kieran Mulroney.

“And it’s cumulative. You really can’t afford to wait.”

A FASTER WAY

To save lives, doctors do the best they can and treat patients with a broad antibiotic.

But Kieran and his colleagues at Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research, UWA and PathWest are working on improving these scenarios.

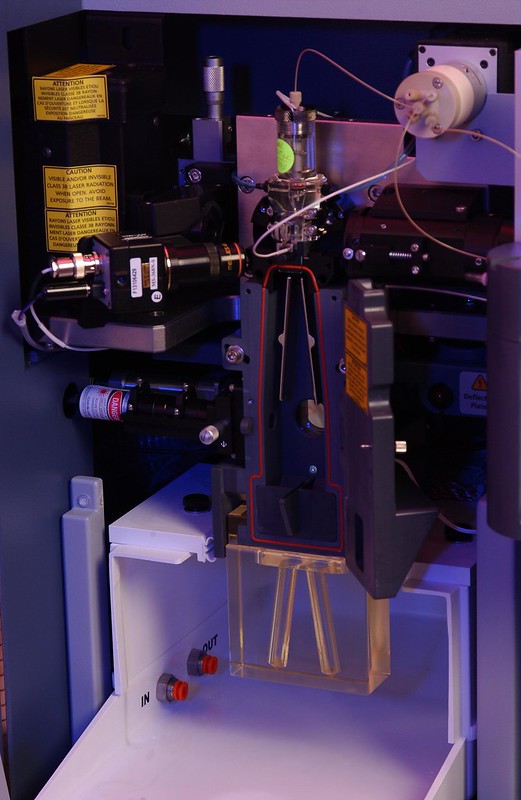

They’re developing a cutting-edge test called ‘flow cytometry-assisted antimicrobial susceptibility testing’ (FAST), which can tell doctors which antibiotics will be effective in 2–5 hours.

REAL-WORLD IMPACT

Kieran returned to university as a mature-age student to finish his undergraduate degree in molecular genetics.

His life experience helped crystallise what he wanted to achieve.

“I wanted to do something that had real-world impact and had some sort of real benefit for people,” says Kieran.

His honours project saw him test fickle bacteria used in mining that only survive in strong acids.

When the time came for Kieran to start his PhD, he joined Harry Perkins. And the team had a FAST prototype up and running within 3 months of starting work on it.

“That was 2015, so it’s been eight years of dedicated development,” says Kieran.

His dedication to the research project saw him become a finalist in the Early Career Scientist of the Year category of the 2023 Premier’s Science Awards.

A PERSONAL APPROACH

The technology used for FAST is now being commercialised through spin-off WA company Cytophenix.

It’s the kind of applied science that Kieran’s always been good at.

“If you [talk] to people about serious infections, it doesn’t take long until … [they] start telling stories about their lived experience,” says Kieran.

“Their grandparent, their child, their partner – and most of those stories don’t have happy endings.”

“Every patient that we talk about in research papers … is a person, it’s a family.”

WHEN THE DRUGS DON’T WORK

Beyond the impact on individual patients, using broad-acting antibiotics contributes to the creation of ‘super-bugs’ (aka antimicrobial resistance).

In 2021, the World Health Organisation declared antimicrobial resistance as one of the top ten threats to global public health.

“The more you use those broad-spectrum antibiotics, the less likely they are to work in the future for other patients,” says Kieran.

“So we really, really need good tests that will give us the answer very quickly.

“The current strategy that is protecting patients’ lives is going to become less effective as time goes on.”

Kieran and the team are working to make the FAST platform even better.

“Looking for new ways to apply technology that might stem the tide of antimicrobial resistance … that’s the sort of big challenge that gets me excited.”