If you look around your bedroom, or in the door pocket of your car, you may have a cool shell you’ve found and kept. Maybe it’s a nice pinky-orange, or has a perfect little hole so that one day you could make a necklace.

If you’ve ever picked up such a shell, a good stick, or a cool rock, carried it around with you, and put it down somewhere else, congratulations! You’ve created a manuport.

Derived from the Latin words ‘manus’, meaning ‘hand’, and ‘portare’, meaning ‘to carry’, a manuport is an un-altered object that has been transported by a ‘person’ away from its place of origin.

Not that your shell isn’t super cool, but manuports are most interesting in the context of archaeology. When attributed to hominins living millions of years ago, they provide a window into the lives of our ancient ancestors.

Stone of Many Faces

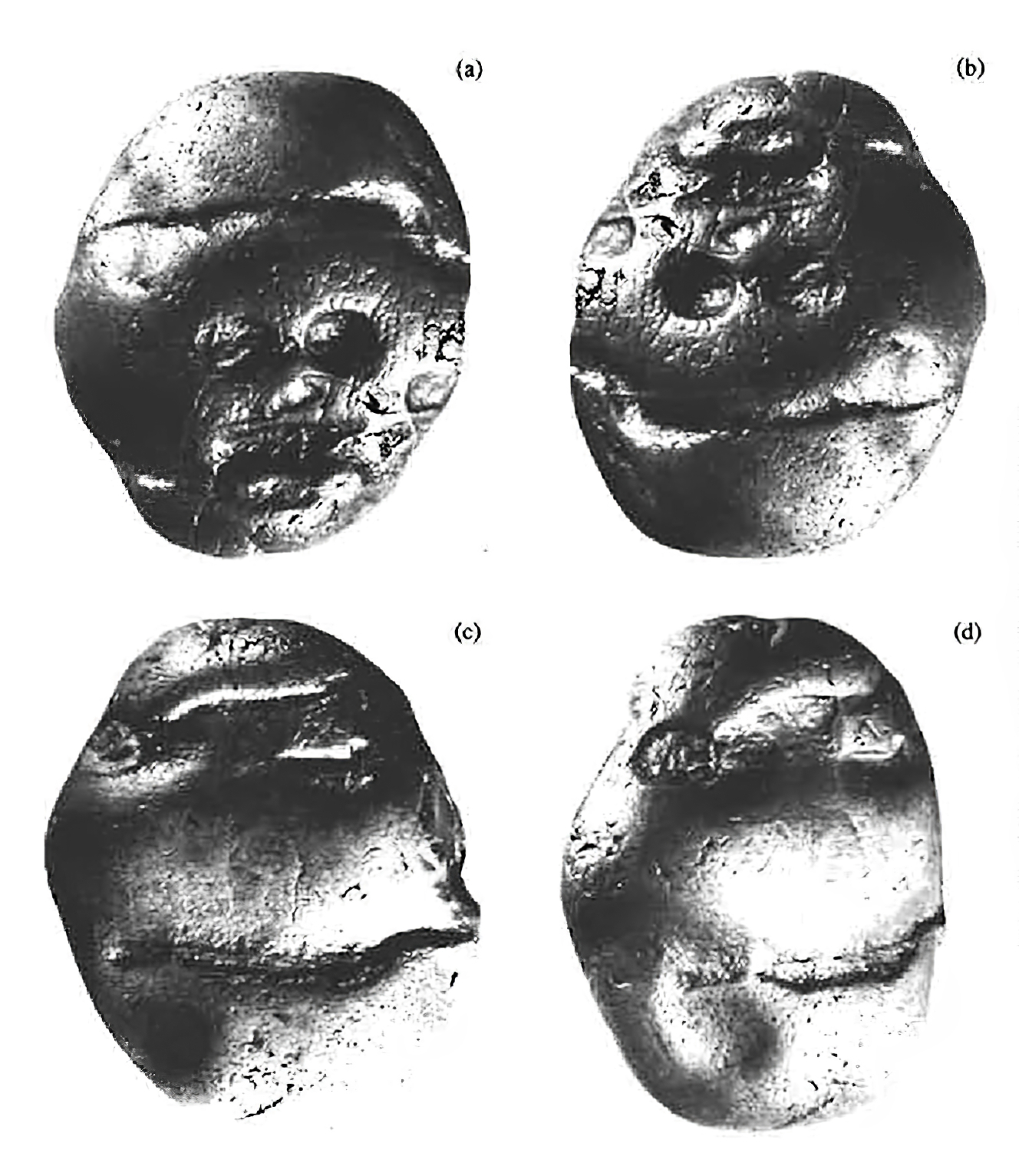

Perhaps the most well-known manuport is the Makapansgat Cobble, a palm-sized rock with distinctive natural markings on it that look like a face.

The cobble was excavated in 1925, at a site in South Africa’s Makapan Valley, which is home to some of the world’s most extensive paleontological records of human evolution.

We think that this stone with a staring problem is a manuport because it’s made of jasperite, the nearest deposits of which are believed to be 32km away from where it was found.

This implies that an individual has carried it across that distance, all before the invention of tote bags.

Based on fossilised bones found in the same geological layer as the cobble, said individual was probably a member of the early hominin species Australopithecus africanus.

Australopithecines are serious contenders for being ancient relatives of our genus, Homo. Bipedal, but with long arms and ape-like facial features, they roamed the earth between 3.3 and 2.1 million years ago.

The Origins of Art

While jasperite is known to have been used to make tools, our anxious little pebble has been left as-is, making the theory that he was chosen for his looks a compelling one.

Besides, look at that little guy! How could you not pick it up!

It’s impossible to discern the motivations of the individual who picked up the cobble, or even know that an ancient ancestor would recognise the markings on the pebble as a face.

If this was indeed why the rock was plucked from its place of origin, it can be considered to be one of the earliest known examples of art.

This interpretation of Makapansgat cobble allows us to imagine that our distant relatives were able to curate objects for their aesthetic value.

A Long History of Cool Sticks

It can be difficult to determine if an unaltered object is in fact a manuport, and many other potential manuports are more hotly contested. Other possible origins include geological activity like landslides, or transport by other species, including as gastroliths in the stomachs of birds.

It’s also contentious to claim that manuports are something that make us uniquely human, since species like bower birds and octopuses are also known to collect shiny or cool objects.

However, next time you pick up a nice rock, you can think about the millions of years’ worth of nice rocks that have been picked up on our pathway to becoming human.