Sweet, sticky, golden goodness! A favourite of great thinkers, from Leo Tolstoy to Winnie the Pooh, honey might be one of the single best things in life.

In WA we’re lucky enough to have some of the nicest honey a bear could want. But to keep it that way, researchers are working on a new method to authenticate WA honey and ensure that any product with a WA label is the real deal.

THE FINEST HONEY IN THE LAND

Honeys produced in WA are internationally renowned. The fabulous flavour and reported health benefits of honeys like jarrah and marri make them a favourite for tourists and locals alike. The honeybees here are also unencumbered by pests like the varroa mite, so WA honey is pesticide free!

Unfortunately, what’s written on your honey jar’s label isn’t always what you find inside. The honey industry is plagued by falsely labelled sugar syrups or inferior honey mixes being passed off as premium products.

Not only does this mean the customer is being ripped off, but honey fraud can seriously harm the livelihoods of high-quality honey farmers, by stealing their business and undermining consumer trust in the industry.

These honey hucksters must be stopped!

THE WHO’S WHO OF HONEY

In most parts of the world, honey is authenticated by looking at pollen residue. The pollen found in the honey should indicate which flowers the bees have visited, but in WA, measuring pollen can get a little messy.

“In WA, we collect our honeys from the diverse natural forest, and in the natural forest, there is quite a lot of flowering occurring at the same time,” says Dr Khairul Islam from the UWA Collaborative Research Centre for Honey Bee Products and Y-Trace.

“The bees might prefer to collect the nectar from one plant … on the other hand, they can collect quite a lot of pollen, for nutritional demand, from different plants.”

With so many flowers the bees might have visited, honey in WA often contains pollen from flowers that haven’t actually gone into making the honey. To deal with this, Khairul and his team have been developing a new way of authenticating WA honey that analyses the honey itself rather than the pollen.

HONEY BARCODES

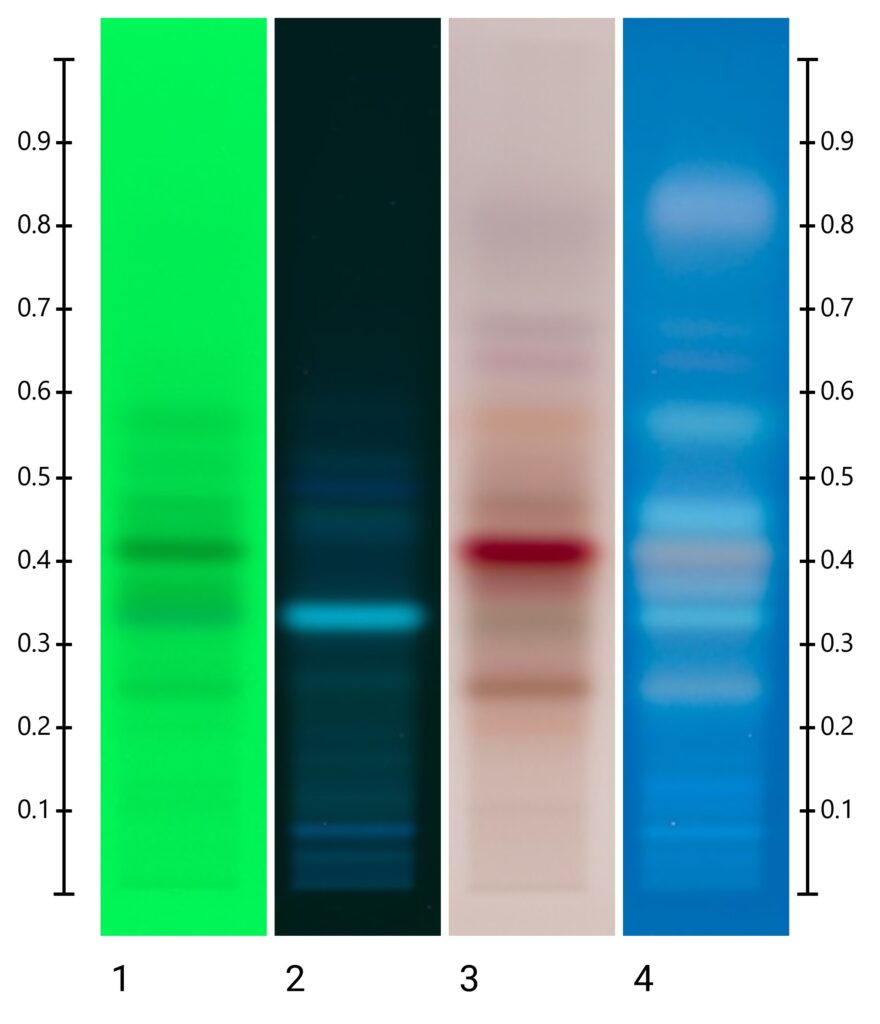

The technique is called high-performance thin layer chromatography (HPTLC) fingerprinting. It involves identifying certain components in the honey that are also present in the nectar it’s made from.

“We extract the phenolic and the flavonoid compounds … these are what give the honey its flavour, colour, aroma, antioxidant activity, antimicrobial activity and other physicochemical characteristics,” says Khairul.

The honey extract is analysed with HPTLC fingerprinting, which allows the different compounds to separate from one another.

“You can think about a strip of paper. If we dip it into a glass of water, the capillary action kicks in and the water starts moving up. So if you put a drop of coloured ink at the bottom, it will carry the ink with it, but due to the chemistry of the ink, it will separate into different bands in different positions. The chromatography works exactly the same way,” says Khairul.

By shining different light frequencies through the honey extract once it’s separated, it’s possible to see which specific compounds are showing up. Then, by comparing them to samples from native nectars, Khairul and the Y-Trace team can pinpoint which flowers the honey has come from.

“You can think of it as like a barcode, where the bars are in different colours,” says Khairul.

This honey barcoding is one of the most reliable methods for authenticating honey currently available, and Khairul wants to see it used far beyond just WA.

“So far, we have already applied our method to some European honey as well as some honeys from different parts of Australia, especially from the East Coast like the Tasmanian leatherwood honey,” says Khairul.

SWEET, HONEST, HONEY

For many Australian apiarists, research that helps prevent honey fraud couldn’t be more welcome.

Rupert Phillips has been a beekeeper in WA for decades. He and his wife Kim own The House of Honey in the Swan Valley, which focuses on producing sustainable, WA native honeys. Over the years they’ve seen firsthand how honey wholesalers have tried to take advantage of uncertain testing.

“Unscrupulous operators would ultra-filter honey so much that you couldn’t even tell the origin of the honey. It had no telltale signs of pollen grains in it or anything. Then they’d blend it with another honey and sell it as that honey,” says Rupert.

These unscrupulous operators undermine people’s faith in the quality and authenticity of honey on supermarket shelves. To help rebuild trust in WA honey producers, Rupert is keen to see increased accountability in the industry.

“Anything that will restore or perhaps bolster consumer confidence is a good thing. People are becoming more and more aware of what they’re buying and the origin of their food … if there’s a national standard or a test which actually determines what they’re eating, well, then of course people are going to go for it.”

The honeys produced from the pristine forests of WA are world-class and deserve to be recognised as the incredible delicacy that they are. Hopefully, new technologies will continue to make sure this sweet treat is kept pure so that we can all enjoy a “small smackerel of honey” without hesitation.