Retired sergeant and police sketch artist Terry Dunnett spent his 30-year career sketching and assisting in hundreds of investigations. But how did he get there, how has the industry changed over that time and is it really like what we see on TV?

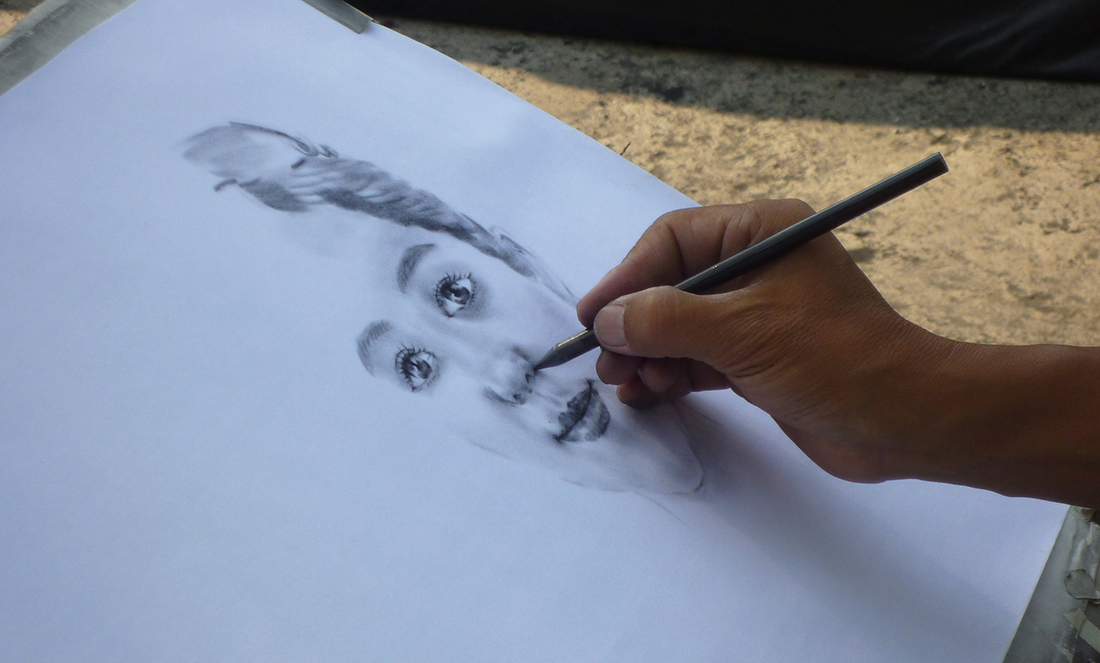

Police officer to sketch artist

Terry joined the WA police force (WAPOL) in 1976, as he was between jobs and thought it might look good on his CV.

Little did he know that his talent and passion for drawing would eventually land him the job of WA’s first police artist.

After a stint in the country and a return to Perth in 1985 as a plainclothes officer, he joined the forensics team in 1988.

“Initially, there was only me and a clerk who used to sort photos and do logistics in the office,” Terry says.

He gleaned most of the information on how to work as a sketch artist from counterparts around the world.

Learning from others

In 1991/92 Terry went on holiday to the UK.

He used this opportunity to visit New Scotland Yard and some metro police departments.

“All did the work quite differently, and I picked out the bits I felt fitted WA best,” he says.

On his return to Perth, he put his own practices in place, such as how to structure interviews and prepare witnesses.

It wasn’t until 1996 that a second police artist joined the team.

“It was then we took over all the detainee and prisoners photos—some 360,000 indexed records—and eventually computerised the whole lot,” Terry says.

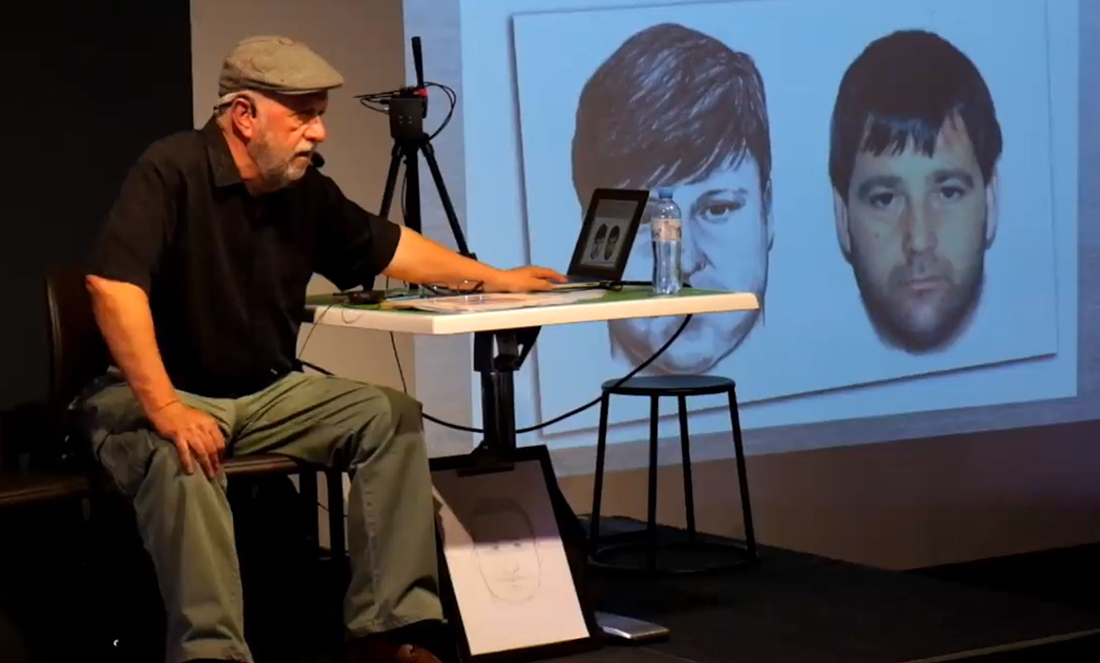

In 2000, Terry was invited by the FBI attaché at the US Embassy in Canberra to attend the FBI facial imaging course held at the FBI Academy in the USA.

The course covered all facets of visual identification of the face.

“We did a lot of work on facial reconstruction—rebuilding faces from skulls.”

He says it’s amazing what you can determine from a decomposed body.

“You can establish from their structure and shape what ethnic group they belong to.”

“And there is a list of flesh depths that will allow you to shape out the face and see what they looked like.”

He also learned a lot from actual case scenarios and reconstruction of crime scenes.

Along comes the digital age

So, is sketching now redundant that the digital age has arrived?

Terry says not entirely—in fact, the FBI still solely use sketch artists for this type of work.

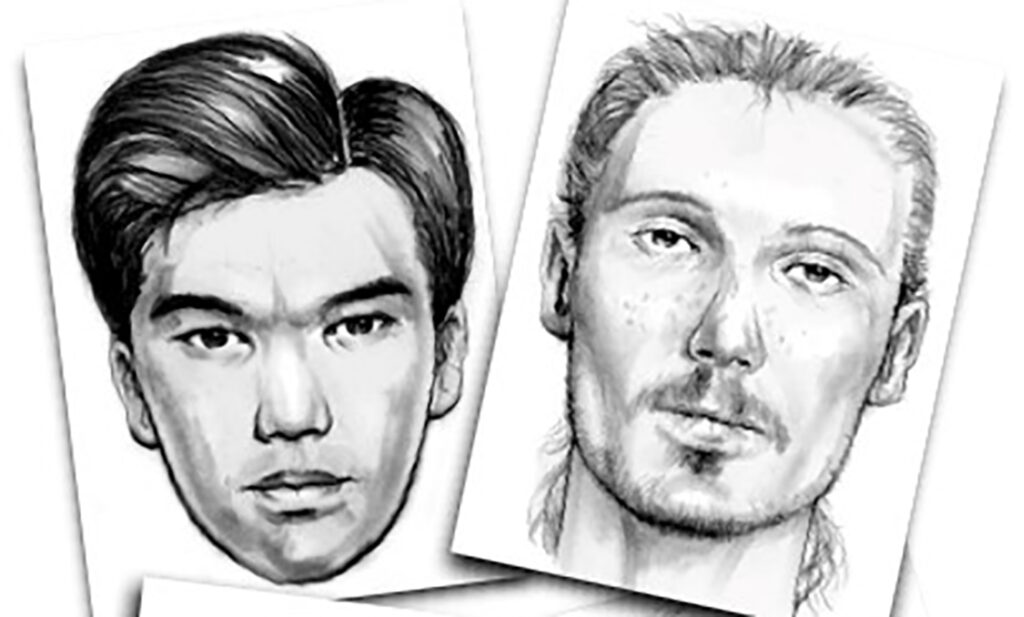

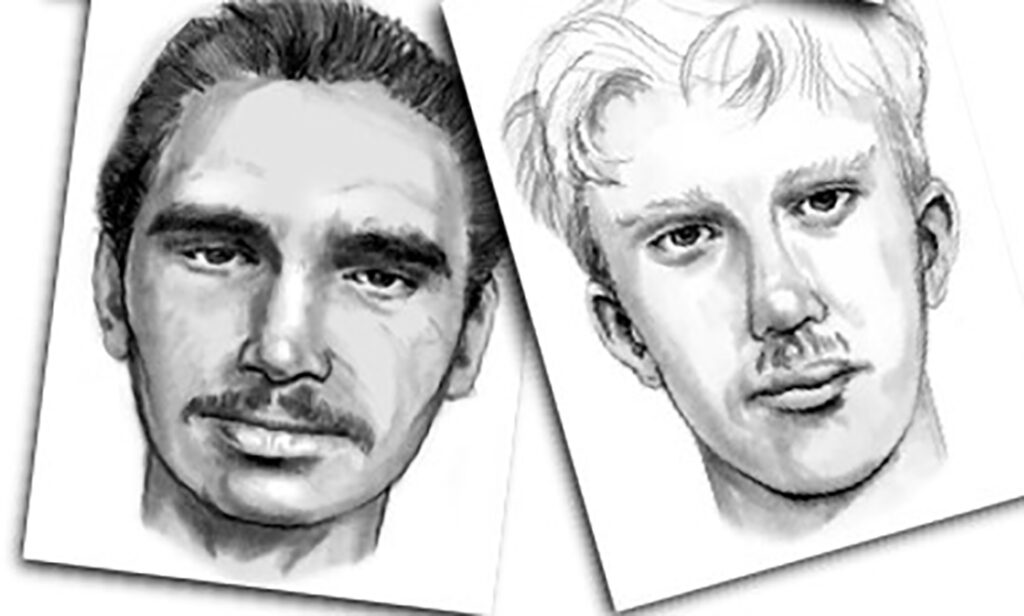

But here in WA, we have an extensive digital database system based on Australian ethnic types, something Terry was instrumental in compiling.

“We talk extensively to the witness beforehand to establish the clarity and recall of what they have seen.”

“Then you show features from the database to a witness and compile the offender’s ‘face’ from there,” Terry says.

“Separate eyes, jawline, mouth, hair and all the components that make up a face are melded together in Photoshop to produce a likeness of the offender.”

Composite face helps solve serious offences

Terry says a good composite can narrow down substantially a target with far more accuracy and above a verbal description.

“It’s an investigative tool that helps lead to the offender.”

He says 85% of those constructed are never seen by the public and are just used internally.

“The ones in newspapers or on TV are ones the police really want the public’s help with.”

“We’ve solved homicides directly down to the composite,” Terry says.

“It’s been an integral part of solving some serious offences.”

‘Jobs we love’ is a regular segment highlighting some of the coolest STEM jobs around. We meet people who love their jobs and can’t believe they get paid to do them.