Some time around 1683, amateur Dutch scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek scraped the plaque from between his teeth and peered at it through a home-made microscope.

Through the carefully hewn lens, he observed “very many little living animalcules, very prettily a-moving”. In other words, bacteria.

Van Leeuwenhoek repeated this somewhat grim experiment on his wife, daughter and two older men, who, by their own admission, kept questionable oral hygiene.

In the old men’s samples, he found “an unbelievably great company of living animalcules … that all the water seemed to be alive”.

Credit: Jan Verkolje/Wellcome Collection

Van Leeuwenhoek was captivated by a miniature world.

Nearly a decade earlier, he had reported seeing tiny organisms moving about in a freshwater sample. This is credited as humanity’s first observation of bacteria.

Throughout his life, van Leeuwenhoek obsessively collected samples from the world around him. Ponds, streams, rivers, lakes, plants, animals and people were all potent sources of potential wonder.

His studious observations revealed that human bodies were crawling with a tiny, invisible populace.

Humans were not simple, bounded creatures, but thrumming conglomerations of cells, molecules and atoms that we simply borrowed for a time. So how much of the human body is really human?

Calculating the microbial self

Three centuries after van Leeuwenhoek’s discovery, scientist Thomas Luckey estimated how many bacterial cells might live in a single human colon (most human microbiota live in the gut).

Luckey’s figure, published in 1972 in a paper on intestinal microecology, was an elegant, back-of-the-envelope calculation based on estimates of bacterial population in faeces and the intestine. It was never intended to be the final word.

He put the ratio at 10:1, meaning there would be 10 microbial cells for every human cell in the body.

That stunning figure was repeated in paper after paper for four decades until a team of researchers revisited the question in 2016.

In their study, the researchers established a more realistic estimate of 1.3:1 or about 30 trillion human cells and 39 trillion microbial cells in a “reference man” weighing about 70 kilos and about 1.7 metres tall.

While a much more reserved estimate, it still shows the average person is, marginally, outnumbered cell for cell.

Necessary hitchhikers

It’s tempting to see the microbes that live in and on our bodies as hapless passengers or even unwanted hitchhikers. But if they live within us, are they in some way part of us, too?

“It’s a really interesting question,” says Associate Professor Andrea Stringer, who leads the Gut Pathology and Microbiome Science Group at the University of South Australia.

“For example, the gut bacteria live in the lumen of the intestine, which is basically a hollow tube that passes through us, so technically they live on us, not in us.”

But Andrea points out there are different ways to approach the question, because microbes play a crucial role in many essential bodily functions.

Microbes train the immune system, help to digest complex carbohydrates and synthesise a range of vitamins and other useful molecules, including biotin, vitamin K and folates, among other roles.

“Functionally speaking, they’re probably part of us,” says Andrea.

KEEP CALM – AND KEEP YOUR MICROBES

This dependence on microbes extends to all animal life.

This is exemplified best by so-called “germ-free” animals raised in sterile, isolated environments for scientific study, which invariably suffer from major health issues, including poor immune function and digestion and susceptibility to infection.

The connection between microbes and wellbeing extends to the brain. Studies on germ-free mice show that microbes influence stress response, anxiety-like behaviour and cognition.

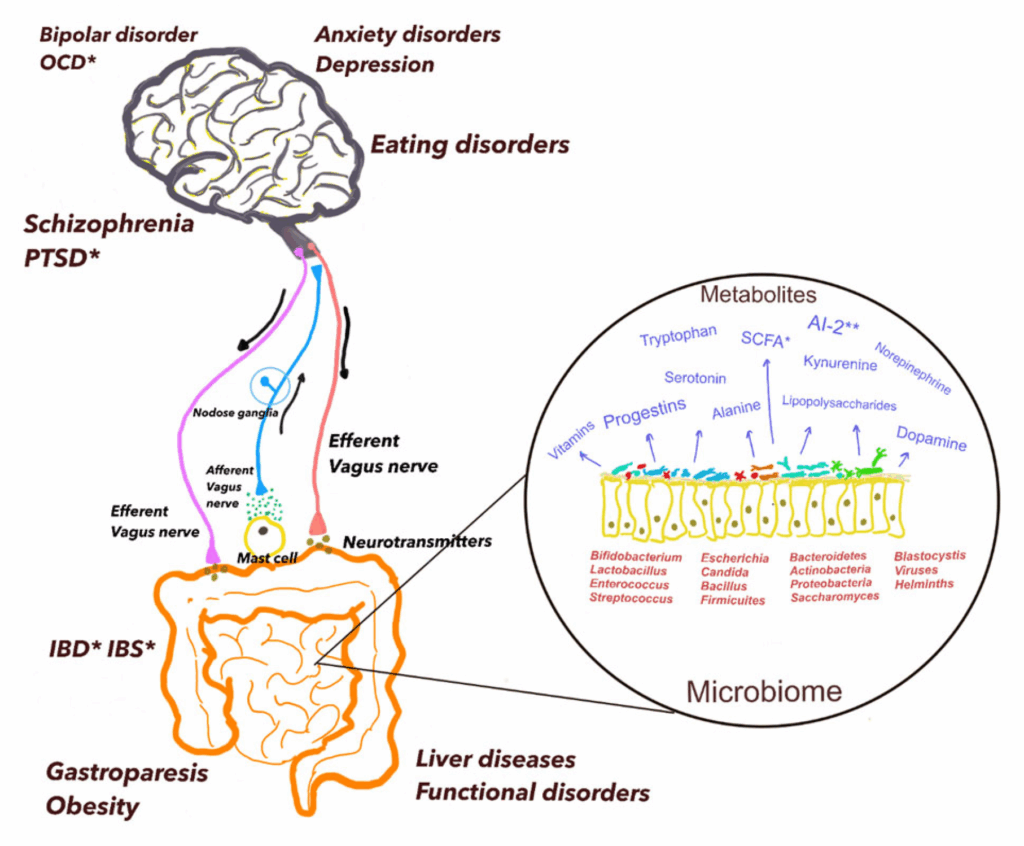

In humans, a powerful link between the gut microbiome and psychiatric conditions like anxiety, depression and PTSD is becoming better understood.

Credit: Ankita Verma, Sabra S. Inslicht and Aditi Bhargava via MDPI

This link appears to exist because of a multi-way communication system between the digestive and central nervous systems, known as the gut-brain axis.

“In basically any psychiatric disorder people have looked at, the microbiome looks different to a normal, healthy sample,” explains Dr Caitlin Cowan, a behavioural neuroscientist at UNSW Sydney.

This interrelationship between humans and their resident microbes threatens the boundaries between self and other.

If our bodies cannot survive without the infinitesimal creatures living within us and our mental health depends on their finely tuned balance, what is it, in the end, that distinguishes us?

Genetic code

Most people credit the discovery of DNA to Francis Crick and James Watson, who published their description of the twisted-ladder deoxyribonucleic acid molecule in 1953.

It’s lesser known that they owe that discovery in part to the pioneering X-ray crystallography of Rosalind Franklin or that a 1944 experiment had already demonstrated that DNA, not protein, was the “transforming principle” responsible for passing on genetic traits between bacteria.

But the story of DNA winds back even earlier.

In 1869, 25-year-old Swiss biochemist Friedrich Miescher discovered a new molecule in cells, which he named nuclein. Miescher’s nuclein was what we now know to be DNA.

Not only was the young scientist the first to isolate this substance, he was the first to suggest it might be involved in heredity.

The discovery of DNA revolutionised human understanding and answered all sorts of questions, like why certain diseases afflicted certain people and how genetic traits could be preserved with remarkable clarity through the generations.

It also introduced a new bias to the Western psyche. Genetic essentialism implied that genes made us who we were – a belief that underpinned some of the most grotesque abuses of power of the 20th century.

But how ‘human’ is our DNA really?

SHARING IS CARING

We share around 98–99% of our DNA with other primates, explains Dr Vicki Jackson, a statistical geneticist at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research.

That figure ranges around 80–90% for most other mammals, although, for some species, it can be as low as 50%.

“In some ways, this isn’t too surprising because mammals all have the same basic body shape – a head, a backbone and four limbs – and all our vital organs are also organised in similar ways,” says Vicki.

“The genetic instructions for building and maintaining these features are highly conserved across species.”

Humans also share a substantial portion of their DNA with non-animals.

About 20–25% of the genes found in most plants have equivalents in the human genome, Vicki says.

And around 30% of the genes belonging to yeast – the single-celled, eukaryotic organism humans have used for millennia to bake bread – have human counterparts, otherwise known as orthologs.

These are derived from a shared ancestor, despite evolving apart for over a billion years.

Credit: guenterguni/Getty Images

What’s more, a small fraction of DNA in the human genome may have been acquired from microbes through a process called horizontal gene transfer (HGT).

In HGT, microbes can exchange genes with one another or take up DNA from their environment. In rare cases, these microbial genes can cross into animal genomes, particularly in cases of symbiosis or parasitism.

Those genes are then passed down to the animal’s offspring, entering the genome of that species, though this is rare and occurrences are often debated.

A 2015 study found that, while invertebrates like fruit flies and nematodes may have acquired foreign genes throughout their evolution, humans and other primates show little evidence of having gained new genes this way since their last common ancestor roamed the Earth. Still, a handful of candidate genes in the human genome may trace their origins to HGT.

In some cases, HGT seems to be possible between animal species – genomic comparisons suggest an antifreeze gene may have jumped from Atlantic herring to smelt (both species of fish), though the exact mechanism for how this happened remains unclear.

“Only a very small fraction of the human genome is uniquely ‘human’,” says Vicki. “What sets us apart mostly comes from small tweaks in sequence or gene regulation rather than brand-new genes.”

Going sub-atomic

If the boundaries between ‘human’ and ‘non-human’ are porous, is our mere physicality – the matter we are made of – what makes us?

It turns out our bodies aren’t made up of a whole lot of ‘stuff’ at all.

The average human cell may contain tens or hundreds of trillions of atoms. Each atom contains a number of much smaller particles and a whole lot of ‘empty space’.

More than 99% of an atom’s mass is contained in its nucleus – the tiny central portion of the atom filled with protons and neutrons.

To visualise the difference in size between the atom as a whole and the nucleus inside it, imagine placing an item the size of a small marble at the centre of a football stadium.

Credit: Paul Kane/Getty Images

It’s commonly said that, if you were to remove all the empty space inside the atoms that make up a human, each of us could fit inside a space about the width of a speck of dust.

But the true picture is a little more complicated, Professor Karen Livesey, a theoretical physicist at the University of Newcastle explains.

“In terms of empty space, if we classify where the mass is, then yes, most of the atom is empty space,” says Karen.

In reality, that picture is contested because the tiny fraction of mass that’s missing comes from electrons. And where electrons are concerned, physics becomes rather weird.

“These electrons, we can’t pinpoint where they’re at because of quantum mechanics,” says Karen. “So instead we talk about the probability of finding the electron.”

This means the vast bulk of an atom – that chasm of so-called empty space – can also be characterised as a ‘cloud’ of potential places where electrons could be.

“If we could somehow detect exactly where the electron is, which is very hard to do, maybe impossible, then yes, the rest is empty space,” says Karen. “But until we do that measurement, it’s everywhere at once, simultaneously.”

This atomic quirk means that, when we touch other solid objects, we’re not simply colliding surface to surface – the two surfaces are being repelled from one another by the electrostatic force.

“The electron clouds between different atoms can’t be pushed together because those electrons repel each other, having the same charge,” says Karen.

If this electrostatic force didn’t exist, could objects simply move through one another like ghostly apparitions because of all this empty space?

“It’s a hard question to answer because it’s one of our fundamental forces,” says Karen. “We can’t imagine life without it.”

So what makes us, us?

What makes, and does not make, a human body is a hotly contested, deeply political question.

“As a geneticist, I like to highlight the importance of our genes, but we’re far more than just DNA,” says Vicki.

“While the code itself is fixed, it doesn’t act alone – health, behaviour and personality all depend on how our genes work in conjunction with environment, lifestyle and experiences.”

“What makes us ‘us’ is very complicated,” says Karen.

“We are made up of atoms that build molecules, proteins and human cells. Our individual differences come from us each having different DNA instructions in those cells, but none of this explains consciousness in an easy way and that is perhaps where the essence of ‘us’ lies.

“Consciousness somehow comes about through complicated electricity transmission between neuron cells in the brain, but that’s about all we know for now.”