Dr Neil Robinson has spent much of his career trying to do things that have never been done before.

Whether it’s finding a new way to turn cooking oil into biofuel or bringing us closer to green hydrogen technology, the UWA research fellow is at home at the vanguard of chemical engineering.

This year, Neil’s talent for innovation has landed him the Australian Institute of Policy and Science’s 2024 WA Young Tall Poppy Award and, as a joint winner, the WA Premier’s Science Award for Early Career Scientist of the Year.

‘MEASURING WEIRD THINGS’

Neil’s field of expertise can be hard to pin down.

“My lab is a cross between a chemistry lab, where you might see chemicals, beakers and fume hoods, and a physics lab, where they’re doing very precise measurements and building equipment,” says Neil.

“I’ve been involved in a lot of quite – on the face of it – disconnected projects but the thing that connects them all is that I’m interested in materials.”

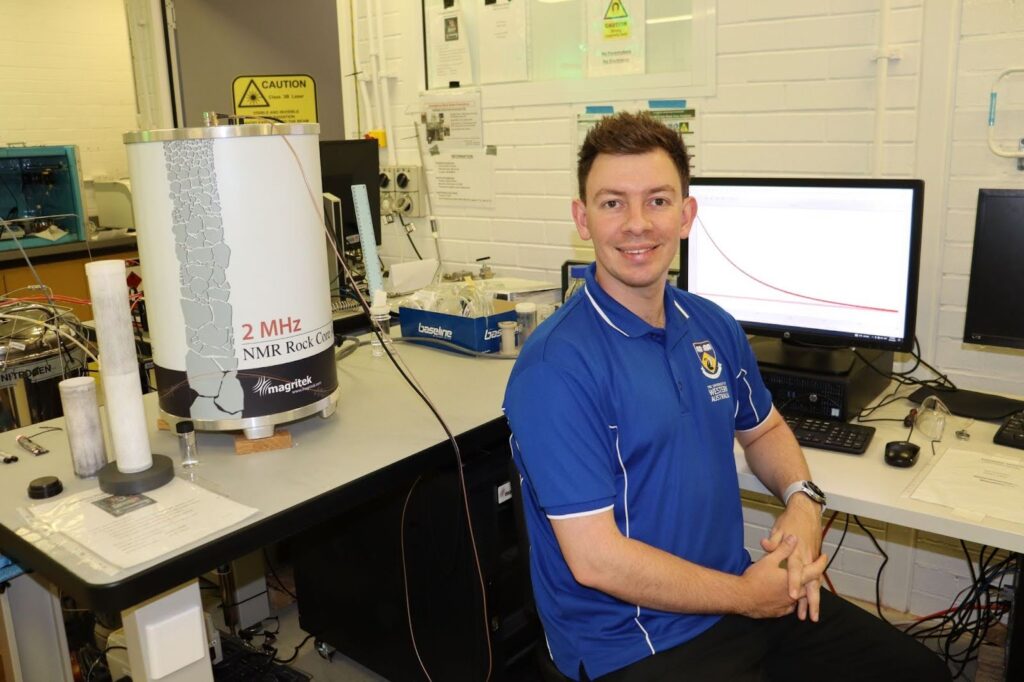

Neil’s current focus is using magnetic resonance technology, similar to medical MRI, to understand, characterise and improve porous materials.

Neil’s work is connected to energy – an umbrella term covering decarbonisation, Australia’s export industry, and critical minerals.

Neil describes his expertise as “measuring weird things.”

‘A CHEMIST, A MATERIAL SCIENTIST, A SALESMAN’

Neil is nearing the completion of a three-year Forrest Fellowship, based at the UWA School of Chemical Engineering.

His job involves writing research papers, teaching students, and applying for grant funding – on top of the experiments.

“You do an interesting combination of fundamental stuff and really applied stuff,” says Neil.

“You’re a chemist, a material scientist, a salesman.”

“I love that every day is different. And I love that what I do can be applied to so many different bits of the science, engineering and energy industries.”

IN THE LAB

Neil says the challenges are his favourite parts of the job.

“You are by definition doing stuff that is difficult otherwise other people would have done it,” says Neil.

“And you’re probably also doing things for the first time, so there’s no precedent for things that might work well, especially when you’re designing new bits of kit.”

“There’s a lot of unknowns and you have to be really happy being in this uncertain world.”

“You have to be happy saying ‘I don’t know.'”

Credit: Supplied

FAILURE THE KEY TO SUCCESS

Failure is an unavoidable part of learning and Neil is no stranger to it.

His fellowship project has been a journey of trial and error, as he works to find a material that will be an effective catalyst in the production of liquid hydrogen.

“I made a material which worked, and that was fine, but I’d say 80% of what I’ve made hasn’t worked,” says Neil.

“You kind of get used to it.”

But he praises the Forrest Foundation for their support of high-risk, high-reward research, when other funding bodies may desire higher degrees of potential success.

CURIOUSER AND CURIOUSER

This pursuit of curiosity, despite the risk of failure, is a quality that has shaped Neil’s career.

Growing up in the UK in a medical family, he imagined becoming a dentist.

“I actually didn’t get the right grades in my high school exams so I ended up doing chemistry,” says Neil.

“I was actually not very good at chemistry at school…but I found it really interesting.”

Credit: Supplied

Neil then pursued a PhD at Cambridge University in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, a subject he didn’t enjoy as an undergraduate.

“I made a career of all the things I have been avoiding so now I’ve just kind of stopped avoiding stuff,” says Neil.

Industry placement at a company that made Nylon during his undergraduate studies cemented Neil’s desire to pursue research.

“I really hated it,” says Neil.

“I did the same thing every day for a year, and any innovation I came up with was pushed back on.”

“It was during that I decided that I’d have to do a PhD.”

INVENTION AND REINVENTION

Neil believes open-mindedness and flexibility have contributed to his success.

“I did a chemistry degree, then I became a surface scientist, so I was really interested in surfaces,” says Neil.

“Then I became interested in porous materials, then I became interested in energy, and now I’m interested in energy and other stuff around net zero so I’m constantly reinventing myself.”

Neil’s next ‘reinvention’ is a lectureship at Queen’s University in Belfast, starting early this year.

He will lead a Master’s course on engineering for net zero, where he hopes to share his passion for embracing the challenges of research head-on with student scientists.