The room is loud and full of chatter in Pintupi (pronounced Pintaby) language. Everyone is eager to share stories about cats.

It’s difficult to understand what’s going on until Dannica interrupts and says in English, “They’re saying cats eat everything.”

I’m on a Zoom call with Dannica Schultz, who’s dialling in from the Kiwirrkurra community, the most remote community in Australia, where she is the ranger coordinator.

The introduction of cats into Australia has a white history, but Traditional owners, like the Kiwirrkurra rangers, are the best in the business of managing pest species. Yet feral cats cause more damage in Australia than anywhere else in the world.

A HISS-TORY OF WA’S CATS

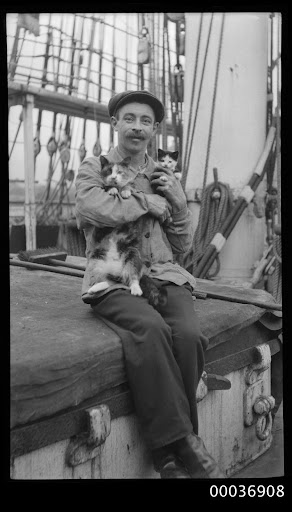

Cats were on the ships when white fellas first arrived in Australia in 1788. They were brought as pets, but later released to control rats and rabbits.

Cats were introduced to Western Australia separately in the 1840s.

“They brang it [cats] from Europe,” says Jodie Ward, a Kiwirrkurra ranger. “They been bringing feral animals for years.”

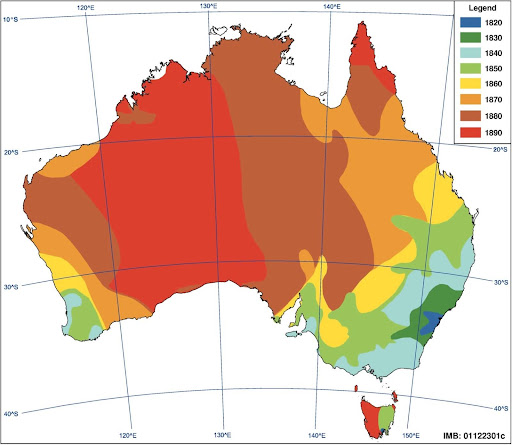

Historical data and stories from Aboriginal people confirm that cats lived across the entire Australian continent by the start of the 20th century.

The Illustrated Handbook of WA from 1900 was one of the earliest references of cat meat as a food source for Aboriginal people.

In 1935, a Western scientist noted that cats were the only non-Indigenous mammal granted an Aboriginal name – another indication of how long cats had been present in the landscape.

All of these instances highlight researchers speaking with Aboriginal people to inform their scientific inquiry. Through their deep and ongoing connection with Country, they have much greater insight than Western scientists about the history and management of feral cats.

LONG MEMORIES

Oral histories point to the ongoing and increasing presence of feral cats.

When I asked the Kiwirrkurra rangers how long cats had been on their Country, they all said that cats had been around for their whole lives.

An article for Time Australia magazine in 1994 reported that, when scientists spoke with Aboriginal people, they “got a pretty consistent picture that … cats had been present for a long time”.

Another study from the late 1980s interviewed Aboriginal Elders from the central desert region, who all said cats had been present their whole life.

Modelling suggests that there are now between 1.4 million and 5.6 million feral cats across Australia, with an estimated 0.27 cats present per square kilometre.

NATIVE ANIMALS AREN’T FELINE SO FINE

Every morning when you wake up, the Australian population of feral cats has killed around 5.5 million animals while you were sleeping.

Through discussions with Aboriginal people from the Ngaanyatjarra Lands in 1979, scientists from the then Department of Wildlife and Fisheries were able to create a database of which animals were present and which had been impacted by cat populations. Even though interviews with Aboriginal people were the centre of this study, none of them are mentioned by name.

Cats threaten over 100 native animal species and are the main contributor to Australia having the highest rate of mammal extinction in the world.

Scott West, a Kiwirrkurra ranger, says “cats prey on birds, mammals and lizards”.

In WA specifically, cats threaten 36 mammal, 22 bird and 11 reptile species and have caused the extinction of up to 27 mammals and ground-dwelling birds.

After being declared a pest species in WA in 2019, there was a national inquiry into feral cats in 2020, with six recommendations on how to reduce their impact. These centred mostly around increasing research and management strategies.

TIME TO GET FUR-REAL

Combining Aboriginal knowledge and Western science is the ultimate way forward to limiting the impact that feral cats can have on Western Australia’s native animals. Kiwirrkurra’s ranger program is leading the way in managing the feral cat population.

Kiwirrkurra is an Indigenous Protected Area (IPA), meaning that the 4.59 million hectares of land in and around Kiwirrkurra is managed strictly by Aboriginal people.

The skills utilised by the Kiwirrkurra rangers to manage their land have been passed on from generation to generation. They have a large team of rangers, including Jodie and Scott, as well as Yalti Napangarti, Yukultji Napangarti (Nolia Ward), Mantua James, Mary Butler, Kim West and Conway Gibson.

The team works according to Kiwirrkurra’s tjukurrpa, or Dreaming stories, using skills that have been passed on from generation to generation.

A subsection of this ranger team are the ‘old ladies’, made up of Yukultji, Yalti, Mantua and Kim. These women have been hunting cats since they were little kids and are considered master cat trackers.

The old ladies can determine whether tracks are fresh, if the cat was walking or running and what direction it was travelling in.

ON THE HUNT

Cat hunts can be planned well in advance or be spontaneous if someone spots fresh cat tracks. Hunts tend to happen during the warmer months in the hottest part of the day and take anywhere from 30 minutes to a few hours.

The hunts that are planned out start at a known threatened species site and have lots of people involved, including the kids so they can learn tjina (tracking).

Kiwirrkurra has ninu (bilbies) and tjalapa (great desert skinks), which are highly threatened by cats and are of great significance to the community.

Yalti says that cats will “wait at the burrow to eat the bilby”.

Scott says that, when cats are brought back to community, they are a good food to share, because they provide more meat than goanna. “It’s better than shop meat,” says Jodie.

Cats are also believed to have medicinal purposes. Anecdotally, eating cat meat helps your heart, muscles, brains and eyes.

However, caring for Country and a tasty meal aren’t the only things motivating the cat hunters of Kiwirrkurra.

BOUNTIFUL CATCH

An integral part of cat management in the remote community is the bounty that hunters can claim. There’s a $100 reward for killing a cat, but to claim the bounty money, Dannica says they have to “bring the guts back to be frozen so we can analyse the stomach contents”.

At this point, someone excitedly yells “you get $200 if you catch two cats!” from the back of the room, and everyone starts laughing. Hunting cats is clearly a source of pride for this team.

Often, the rangers find hopping mice and small birds in the cat guts, but once they found a nyinytjirri (rough-tailed lizard), which has a very spiky tail.

Studying the gut contents can help rangers target their management and hunting efforts.

In just a few months at the start of this year, the community caught 15 cats.

“[They’re] gonna send us broke!” Dannica laughs.

A FERAL FELINE-FREE FUTURE

Hunting cats in the Kiwirrkurra style takes a lot of time and energy, so new methods are being utilised to tackle the problem on a wider scale.

To kick off new management strategies and research initiatives, the West Australian Government committed $7.6 million as a part of the WA Feral Cat Strategy, including $500,000 in grants.

The Kiwirrkurra IPA rangers received some of this grant money to undertake a project to protect a remote ninu population.

Using Eradicat – a sausage laced with 1080 poison – the rangers are going to see how this strategy impacts cat populations and whether it increases ninu survival.

This area was selected by Traditional Owners and the ranger team because it has no permanent water source, meaning there are very few dingoes around – it is just cats and foxes.

It’s an exciting mission for the rangers as they get to share their knowledge and save the ninu, something that they’re very proud of.

Caring for ninu and tjalapa is a particularly important aspect of tjukurrpa, and the Kiwirrkurra IPA ranger team are working tirelessly to achieve this.

Recently, a lot of ninu have been seen around the Kiwirrkurra community. There’s some guesses that this could be due to the strong start to cat hunting efforts at the start of the year.

“Bilby [are] coming up everywhere,” says Yalti.