The Olympics are held aloft as the epitome of human athletics, the highest level of competition possible. But a new contest is vying for the spot at the peak of athletics.

The Enhanced Games are openly allowing – and encouraging – the use of performance-enhancing drugs in athletic competition.

Backed by a band of billionaires, Australian entrepreneur Aron D’Souza is the brain behind the Games. D’Souza claims that current anti-doping laws in professional sport are “anti-science” and restrict athletes from achieving their full potential.

The Enhanced Games will, supposedly, provide “the ultimate demonstration of what the human body is capable of”.

But how well do the Enhanced Games match up to these lofty claims?

Credit: Frans van Heerden via Pexels

“AN EQUAL PLAYING FIELD”

One of the most common arguments against the Enhanced Games is that they compromise the ‘fairness’ of professional sport.

In an interview with the ABC, Sport Integrity Australia Chief Executive David Sharpe said, “Australian athletes have historically demonstrated high levels of integrity, and this undermines decades of commitment from Australian athletes and their sports to clean and fair sport.”

It’s a sentiment shared by many, but it does raise the question of how fair professional sports are to begin with.

Drugs aside, there are plenty of other ways to have an ‘unfair’ advantage in sport.

Credit: Powerzone CC-BY-SA 3.0

“There is basically no such thing as an equal playing field, regardless of an athlete using enhancement drugs or not,” says Dr Katinka van de Ven.

Katinka is a Visiting Fellow with the Drug Policy Modelling Program at the University of New South Wales and a Principal Consultant at 360Edge.

Modern athletics are big business, with each Olympics raking in billions of dollars. Nations that can afford the best training, technology and medical care give their athletes a major advantage over the competition. So is allowing the medically supervised use of enhancement drugs really any different?

“Being an elite athlete from a rich country is very different from being an athlete from the developing world. Using enhancement drugs just adds another layer,” says Katinka.

The Enhanced Games are offering exorbitant prizes for athletes who break world records. Olympic medal winning Australian swimmer James Magnussen said he’d “juice to the gills” to win the $1 million prize for breaking the 50m freestyle world record.

With money like that on the line, some athletes are sure to receive more support than others.

“Some athletes in the Enhanced Games will have access to the highest-quality substances while being monitored by the best medical team, whereas others will not,” says Katinka.

Is that fair? No. But within the confines of a competition like the Enhanced Games, is the open use of enhancement drugs really any less fair than the many other advantages athletes might receive?

RISKS TO HEALTH

Of course, there’s more to be concerned about than just fairness. The Enhanced Games organisers claim the event will be held to the highest medical safety standards, but there’s a possibility that some athletes might be led to taking excessive risks that threaten their physical and mental health.

“The risk with the Enhanced Games’ no limitations … is that there is the risk athletes would use very high quantities and a lot of different substances, even when there is not a lot of evidence of their effectiveness. Basically a ‘just in case’ approach. And the more people use, the higher the risk of health harms occurring,” says Katinka.

There’s also a concern about how the Enhanced Games might influence drug use culture more broadly, particularly among younger people.

“We risk signalling that using enhancement drugs is a normal part of sport and a normal part of preparing for a sport competition. We know that the younger people start using substances, the higher the risk is of developing problems with their use.”

Credit: Getty Images

MEDICAL SUPPORT

However, the open, medically supervised use of enhancement drugs could make things safer for athletes.

A 2014 review estimated that 14–39 % of adult elite athletes use doping.

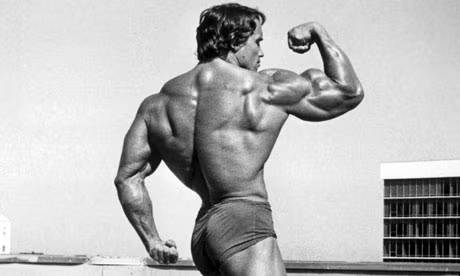

In some competitions, like bodybuilding, the use of enhancement drugs is all but assumed, with separate, ‘Natural Bodybuilding’ competitions needed for those who don’t. For those athletes already using performance drugs, the need to hide their use can have dangerous consequences.

“Currently, enhancement drugs use is largely hidden in elite sport, and anti-doping policies have the unintended consequence that they can increase risky behaviours,” says Katinka.

“Athletes will use enhancement drugs that cannot be detected but potentially are more dangerous … or it may lead to athletes not accessing health services when they experience problems with their use.”

In some cases, athletes might even forego the use of medically prescribed drugs.

“Applying for a therapeutic use exemption is a complicated and costly administrative process. In some cases, it may lead to athletes being denied best-practice medical care,” says Katinka.

By providing a legitimate stage for drug-enhanced competition, the Enhanced Games could help prevent these dangers and even reduce the use of drugs in ‘natural’ athletics.

“Allowing medically supervised enhancement drugs can potentially have a number of positive consequences,” says Katinka.

WILL IT WORK?

Frankly, what the success and impact of the Enhanced Games will be is anyone’s guess.

Maybe they will prove to be a safe, controlled way for athletes to use enhancement drugs – or maybe they’ll inspire reckless and dangerous use among athletes and amateurs alike.

Perhaps they will provide a transcendent example of human achievement – or they’ll be seen as a tasteless spectacle that no serious athlete would compete in.

There’s only one way to find out.